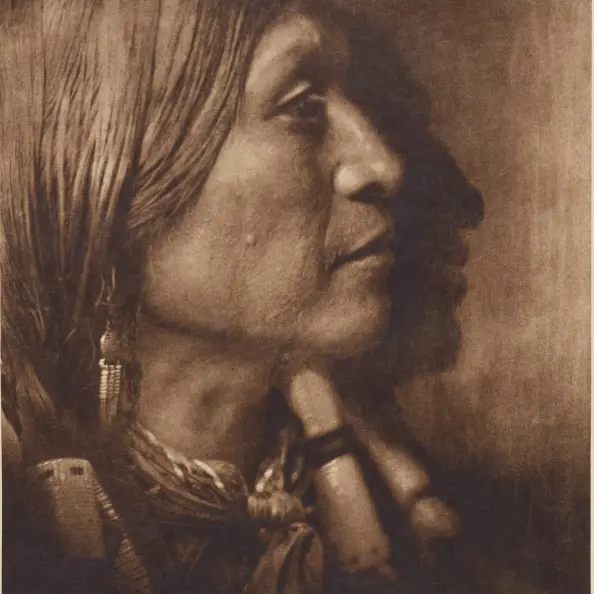

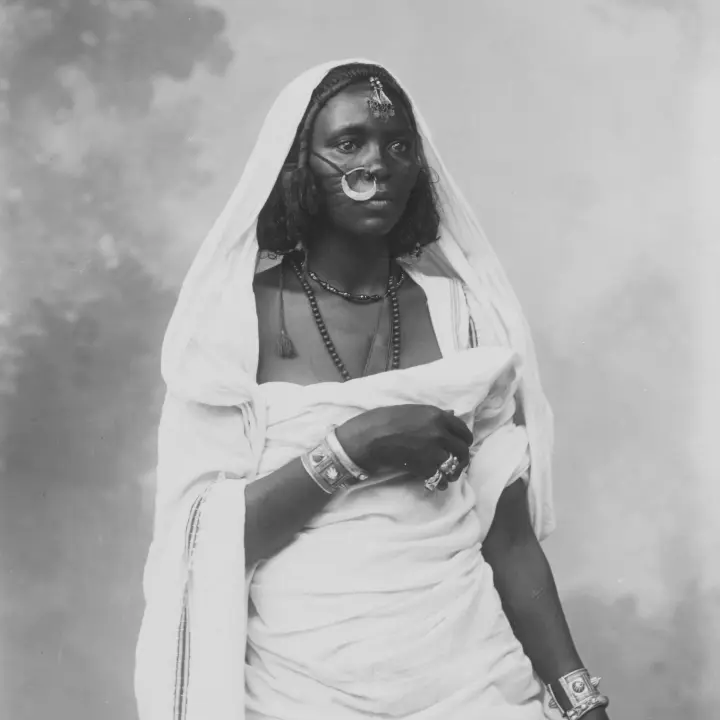

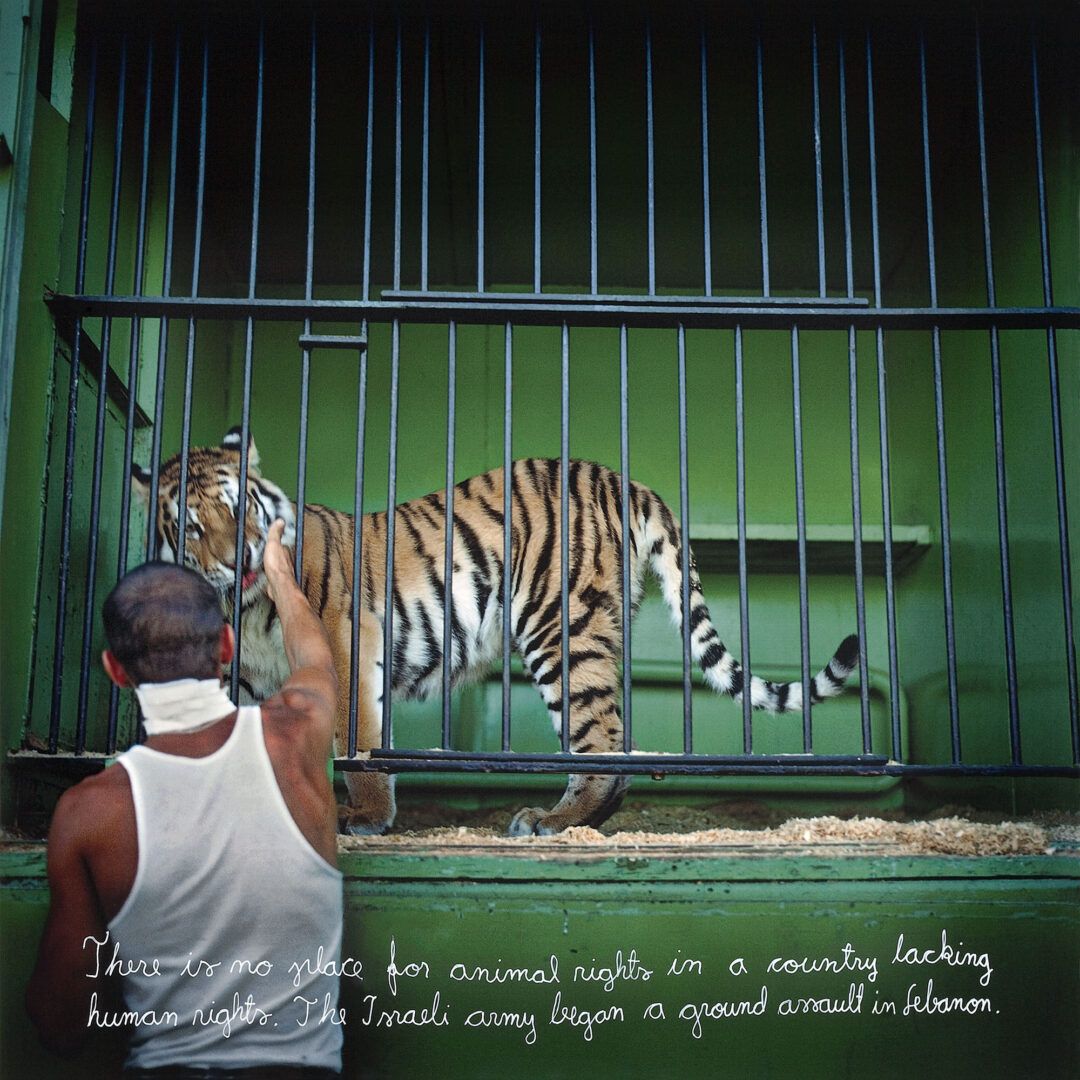

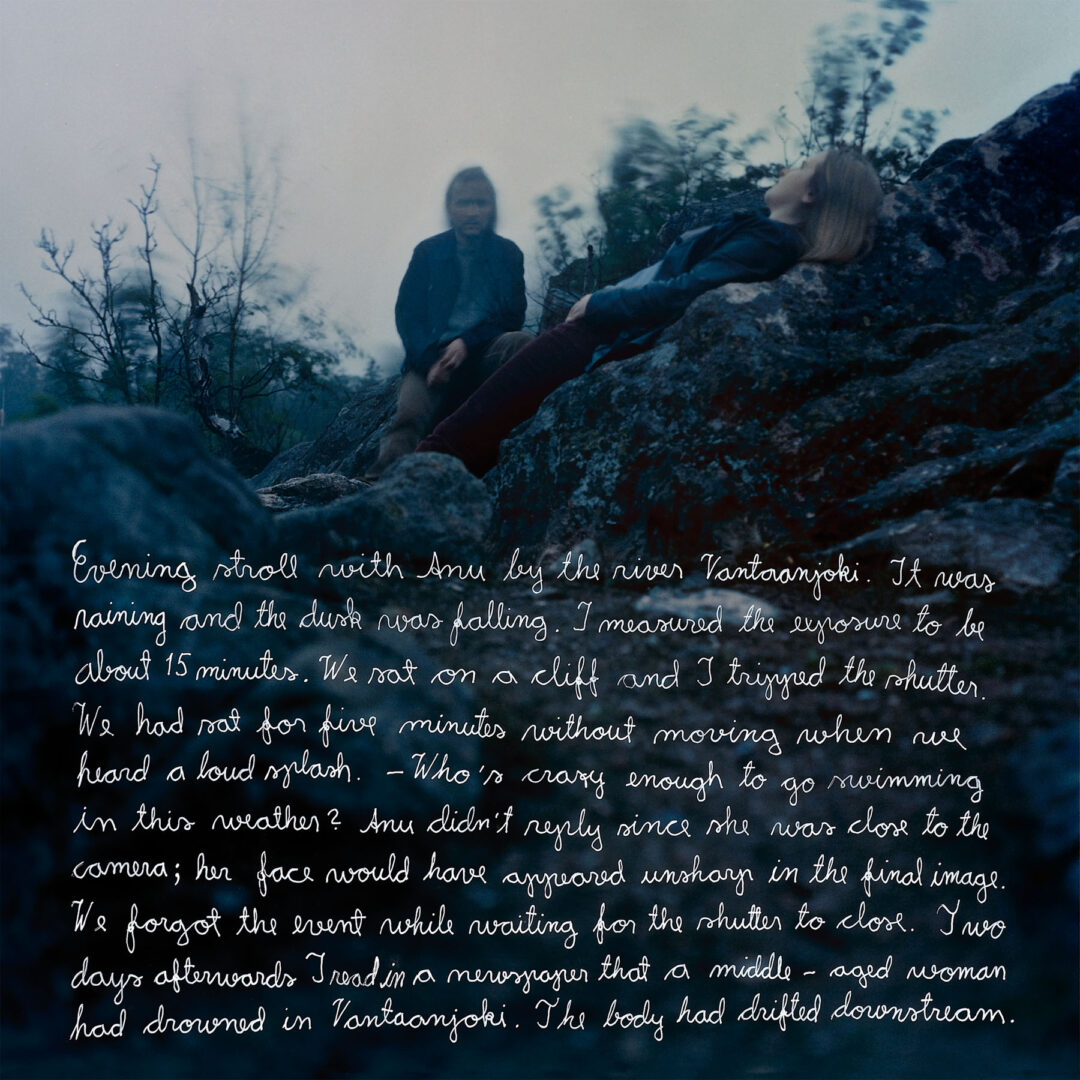

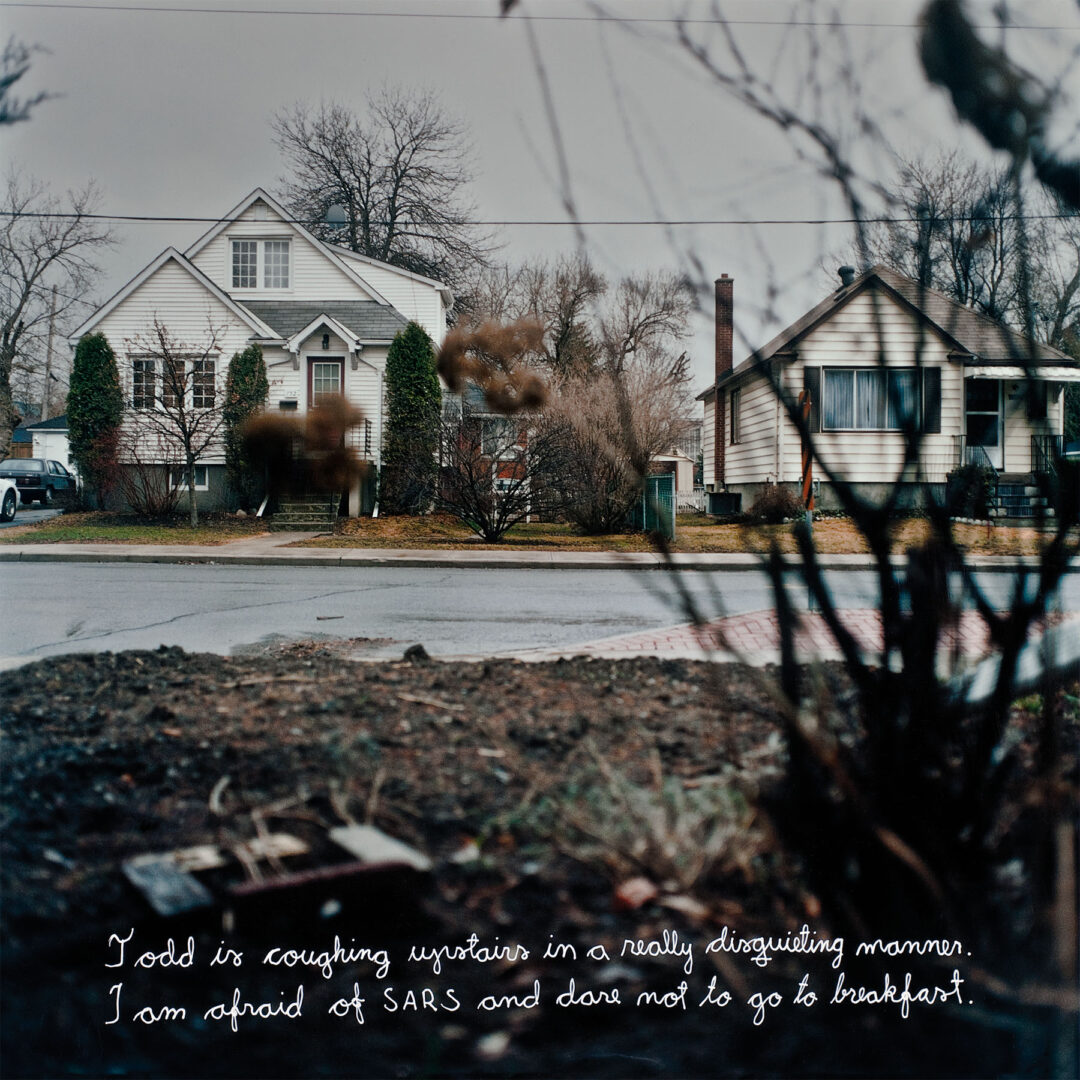

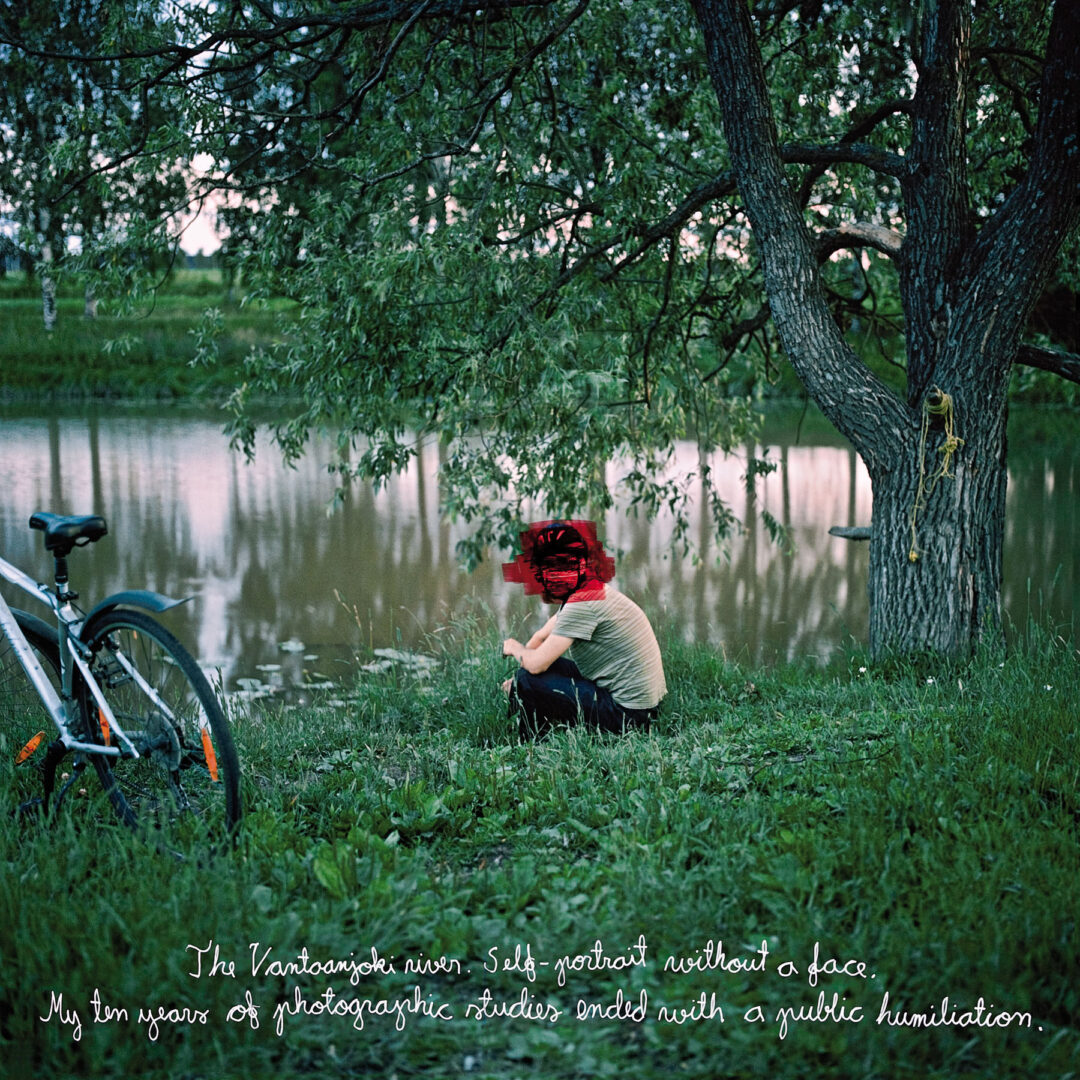

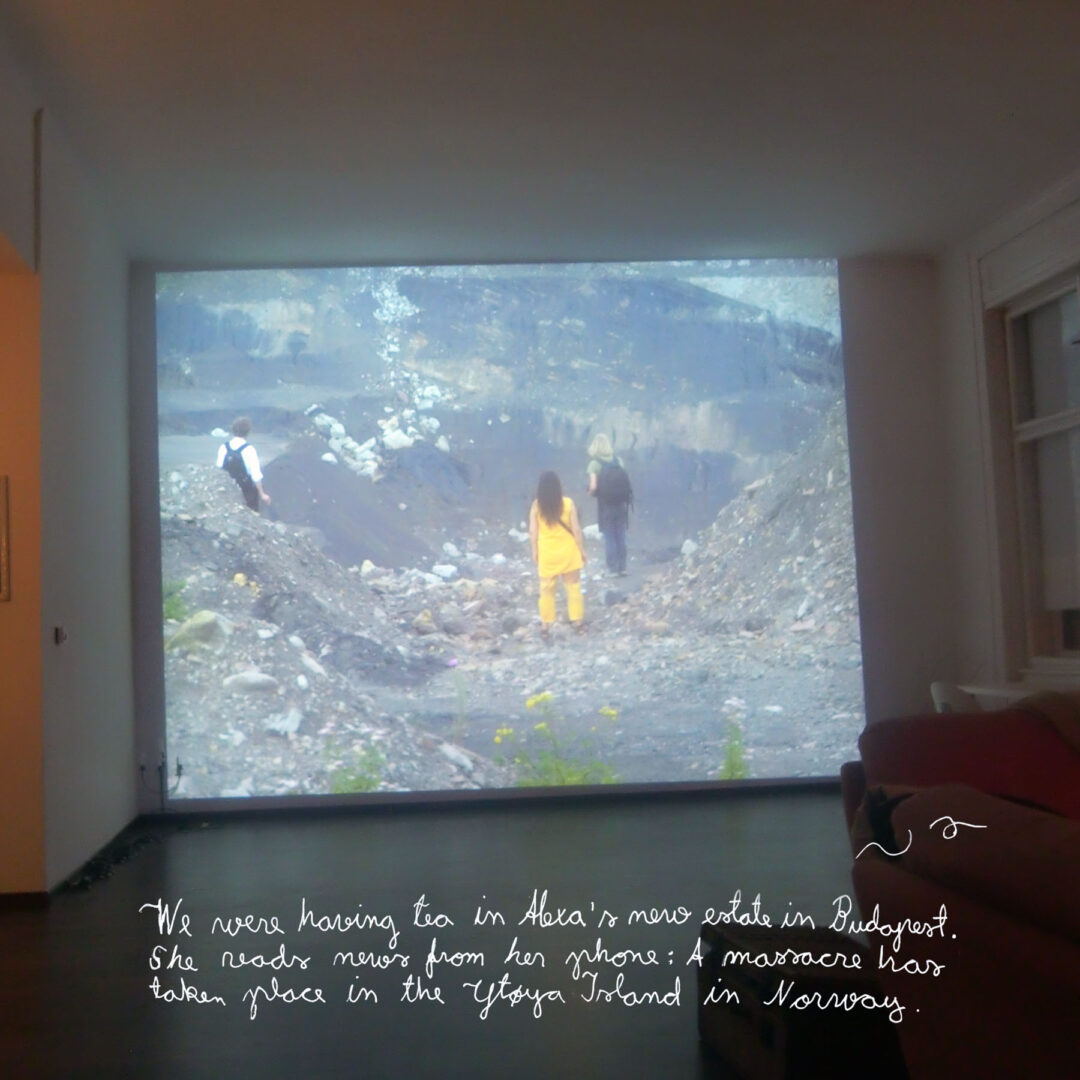

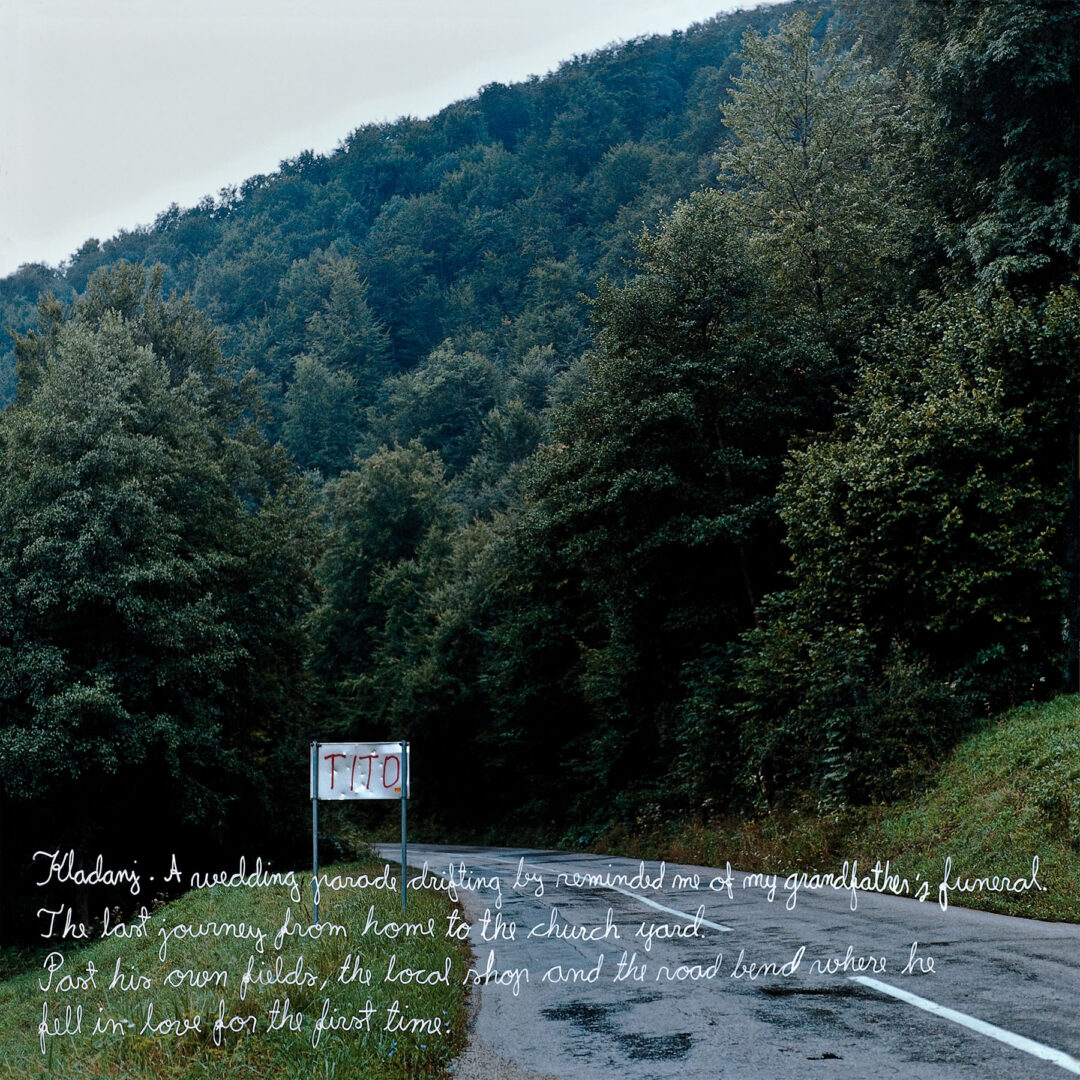

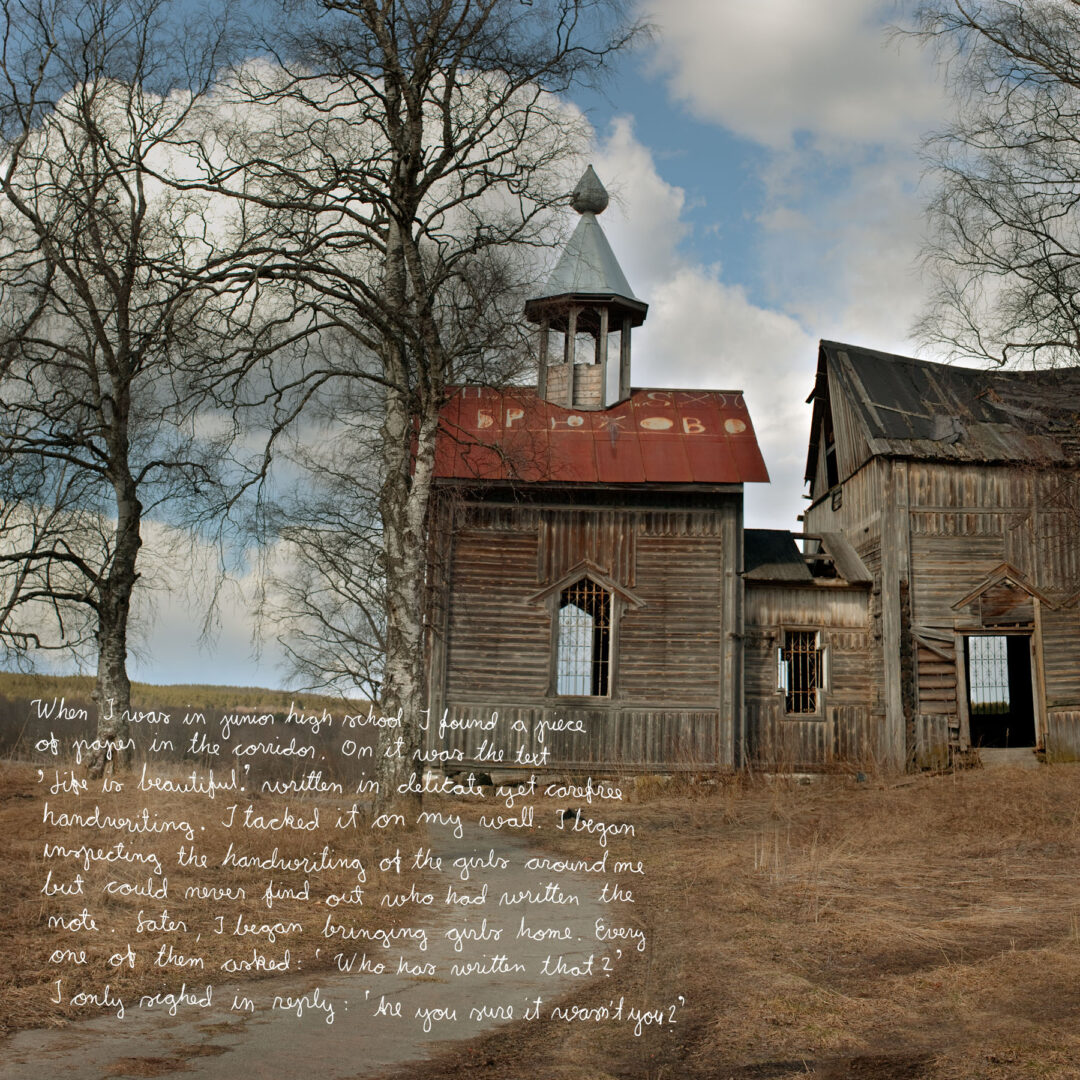

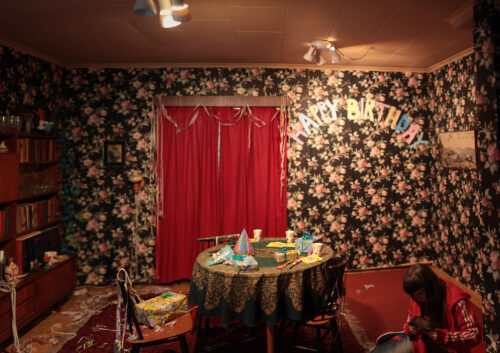

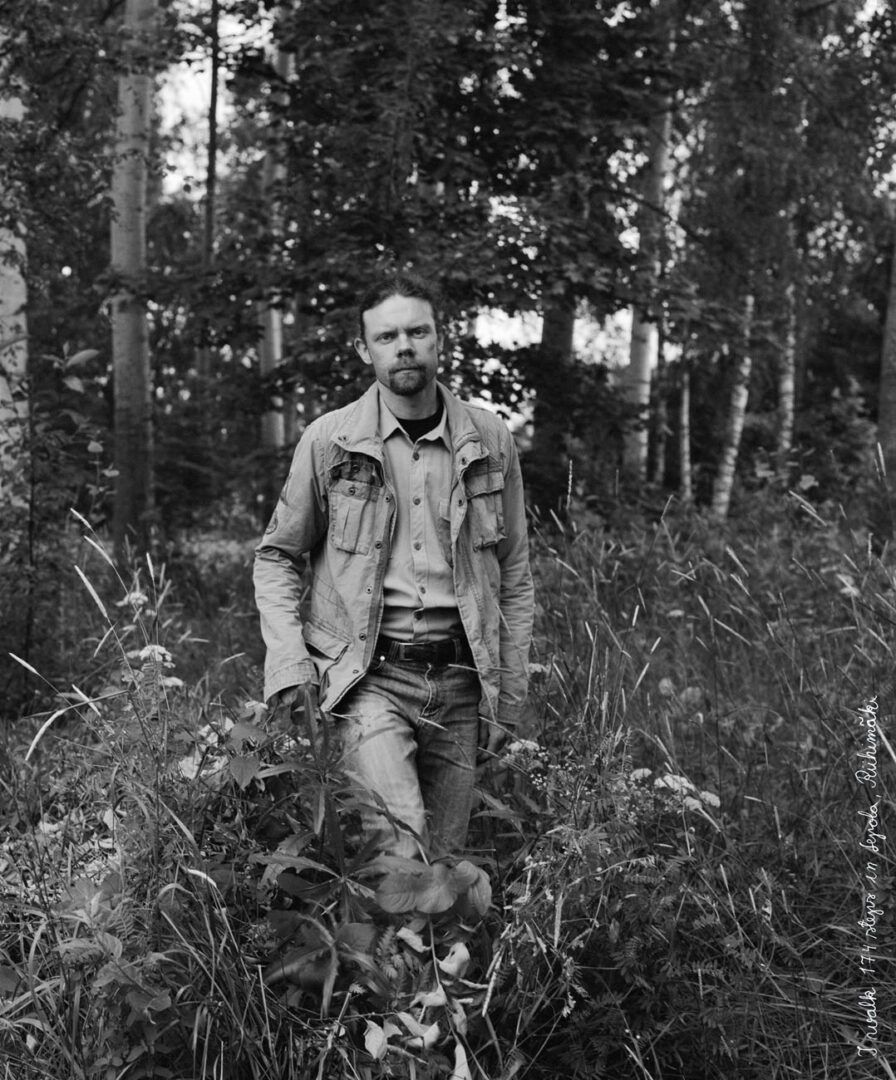

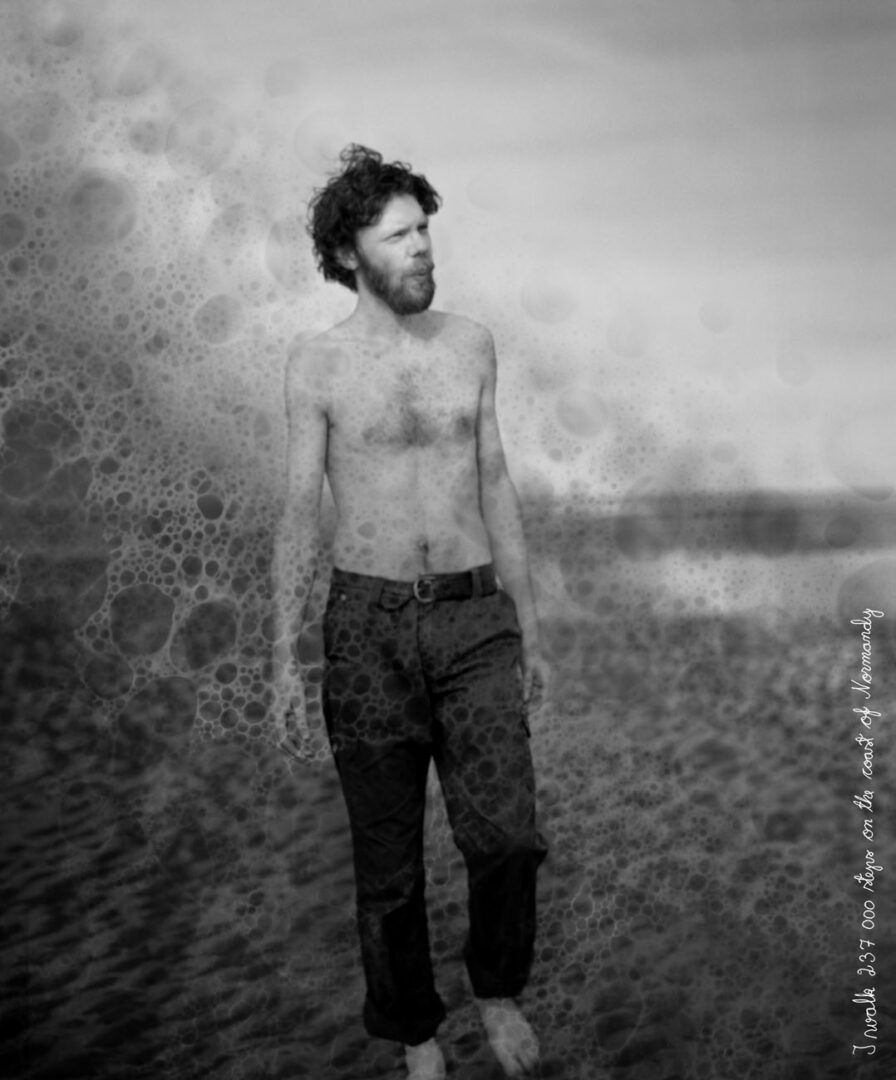

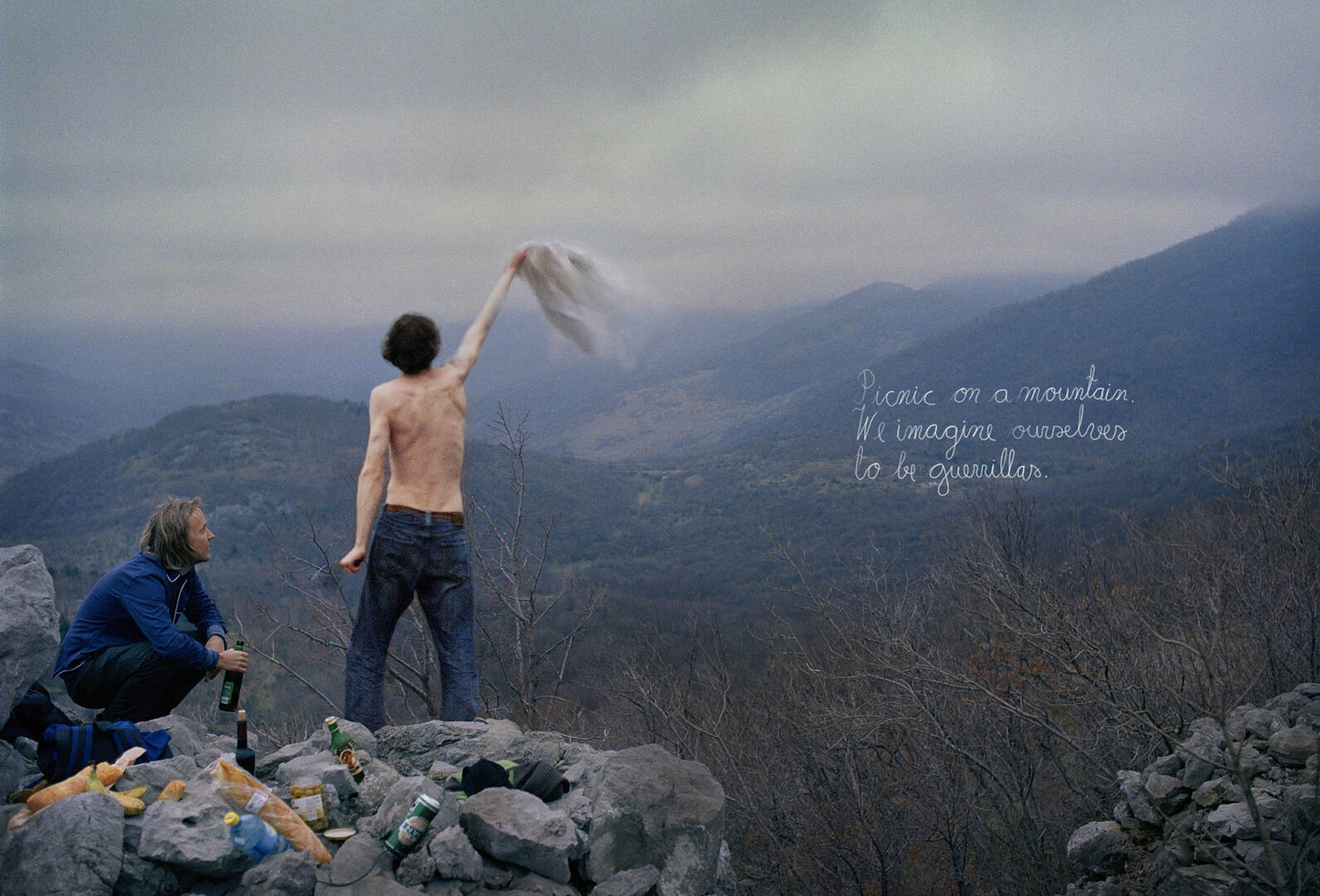

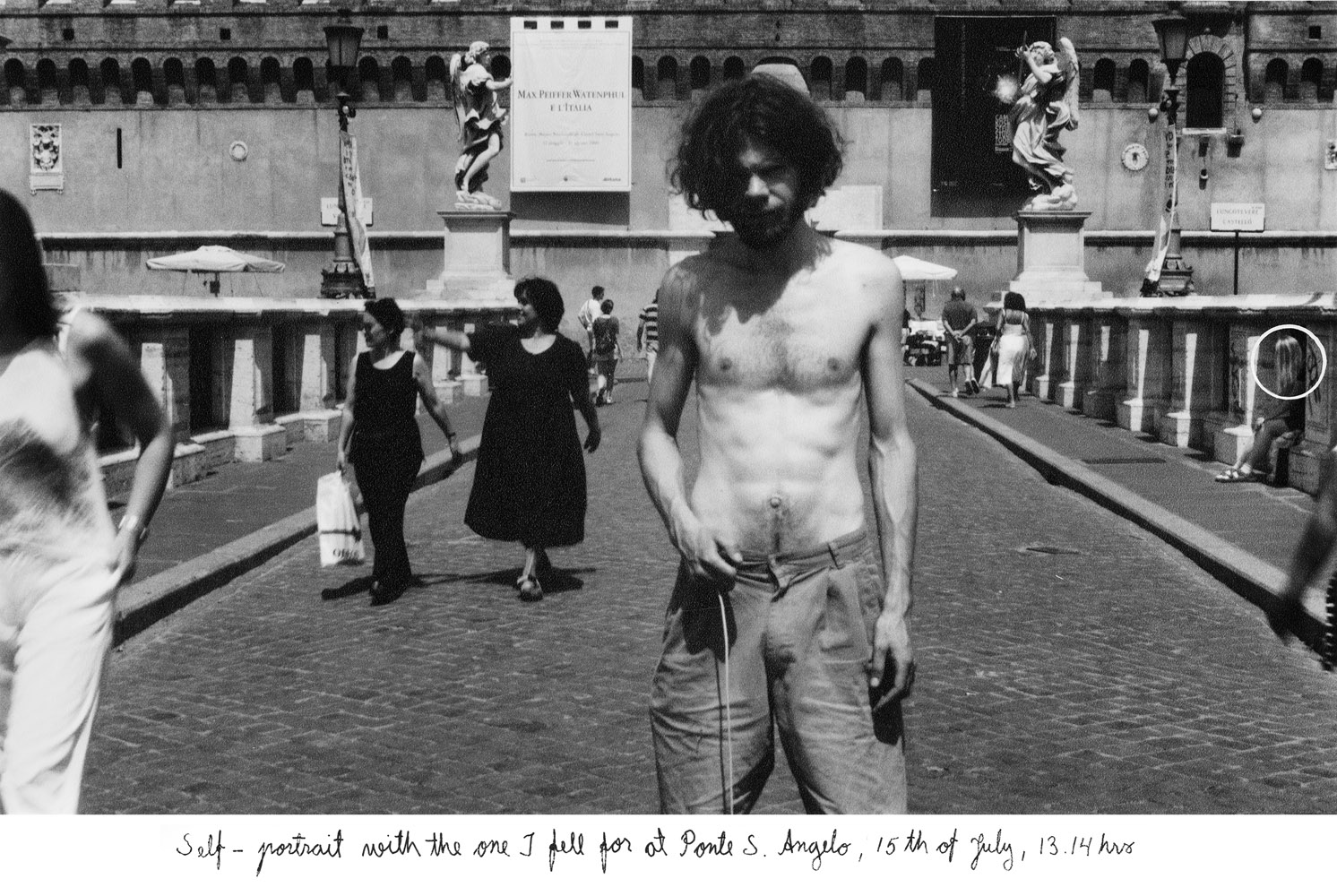

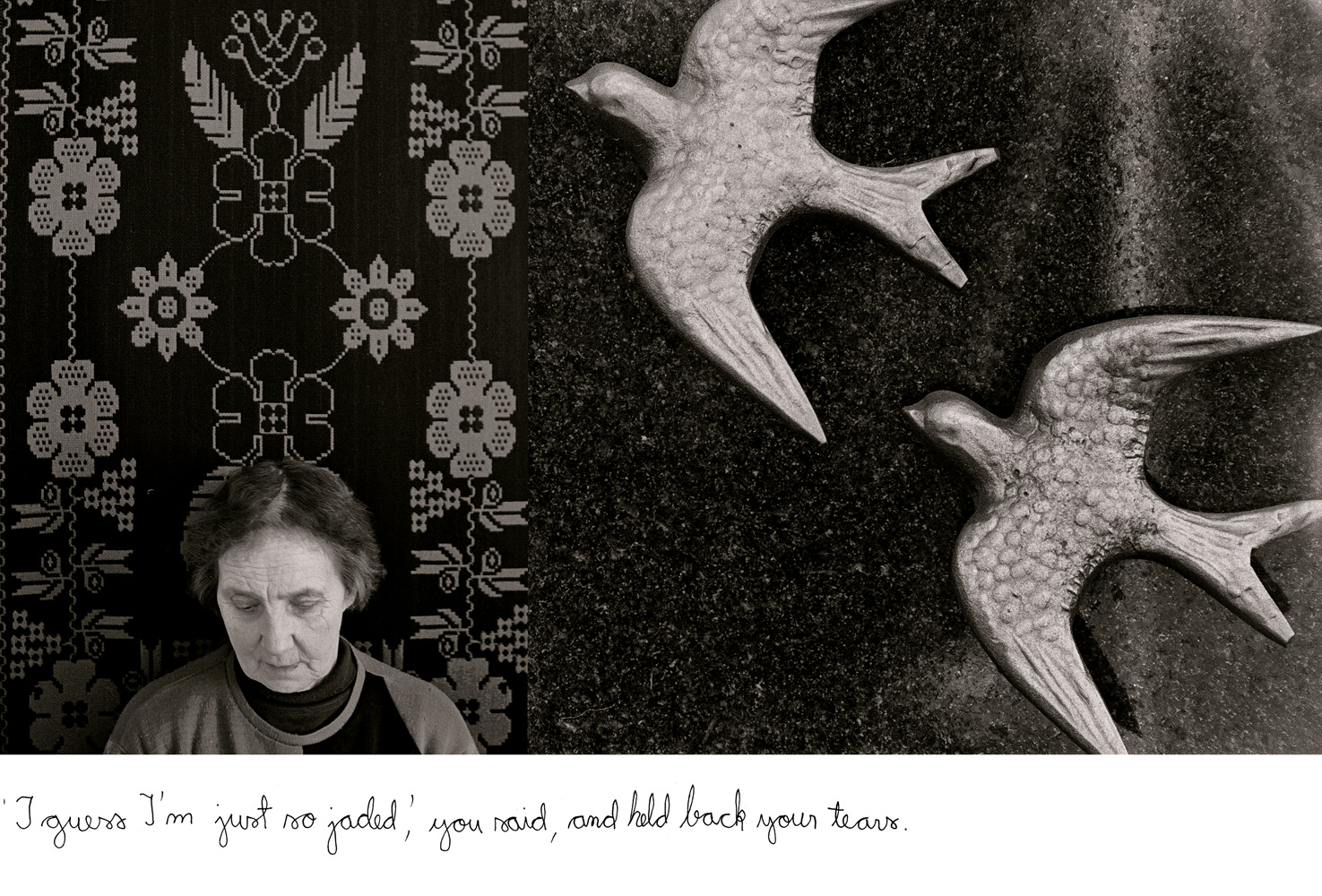

In 2005 I bought from a flea market in Vallila, Helsinki, the written chattels of an

unknown woman. As I studied the material over the years her life and persona began

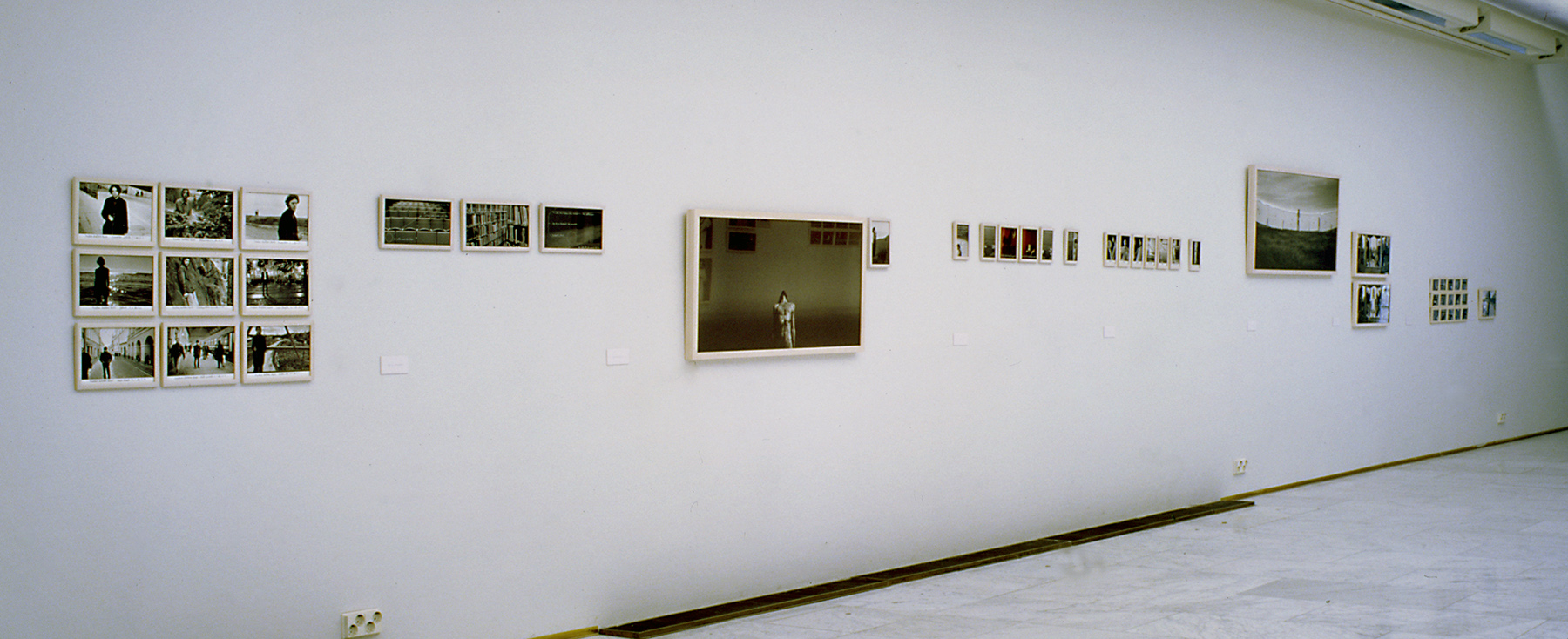

to open to me. I made a portrait of her to my series ‘Alienation Stories 2009’. This

reconstructed portrait had lots of inherent deficiencies and I never finished it.

However, it was a catalyst for a much more detailed project, ‘Atlas of Emotions’.

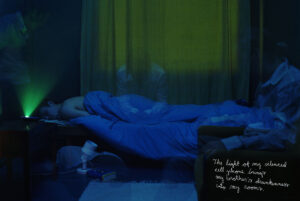

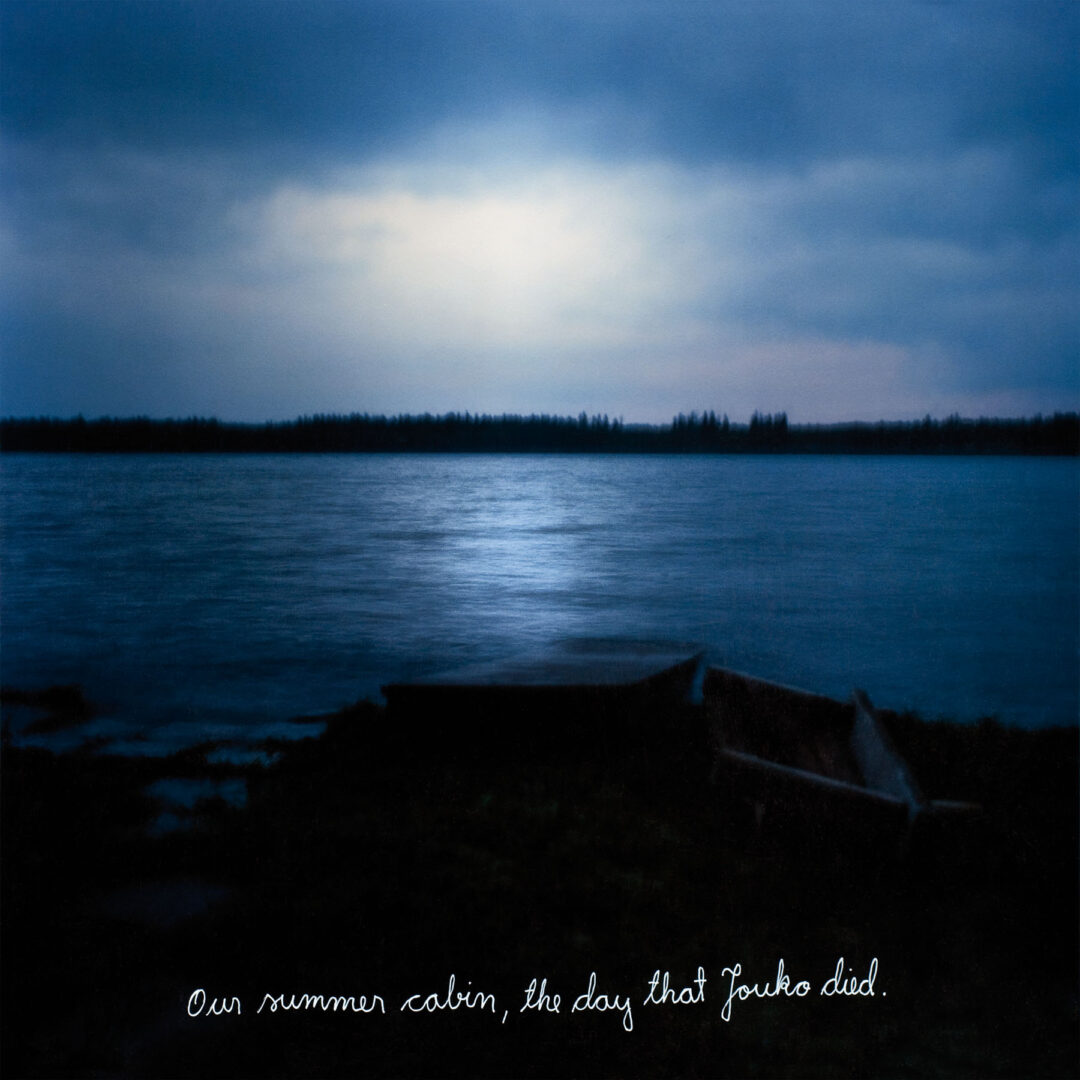

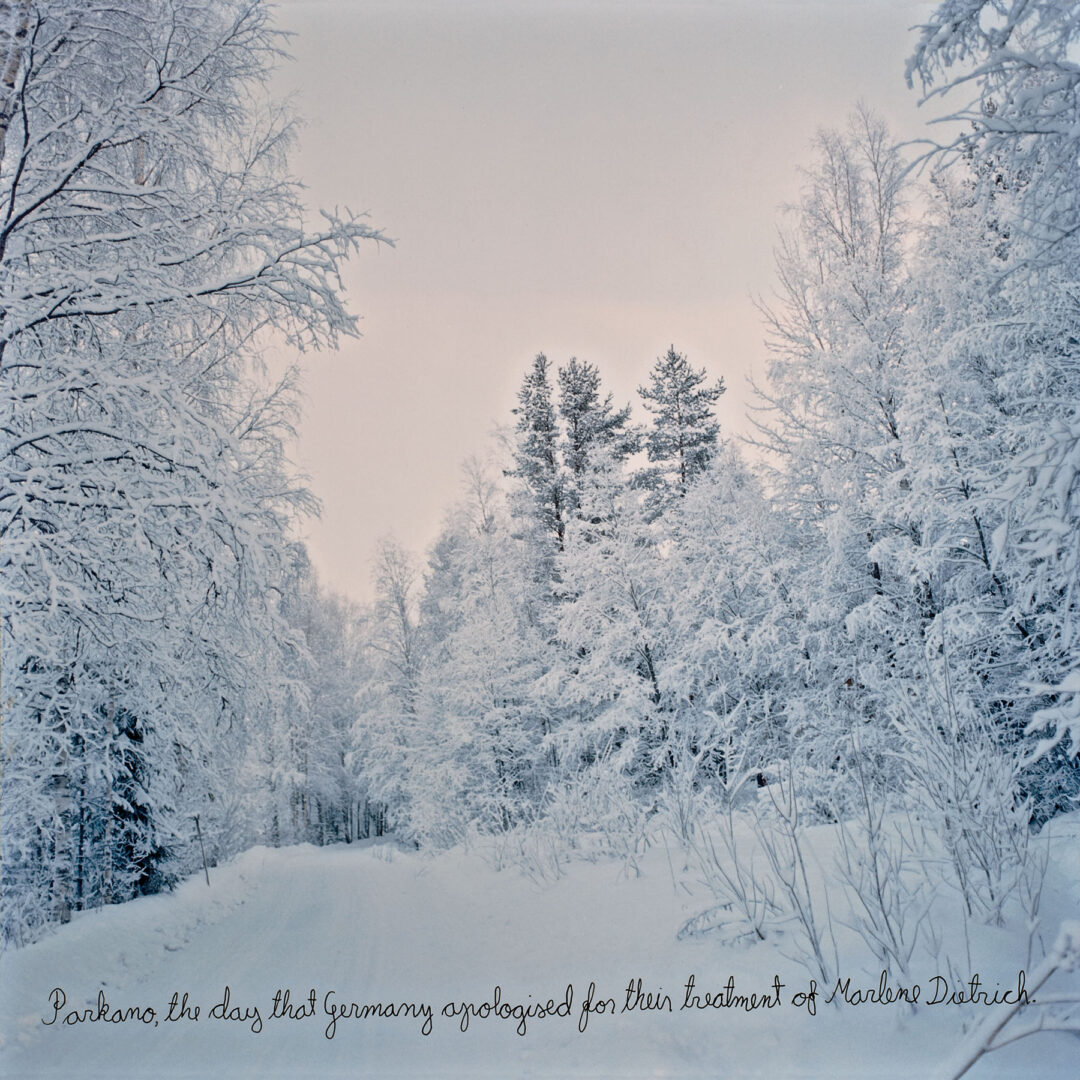

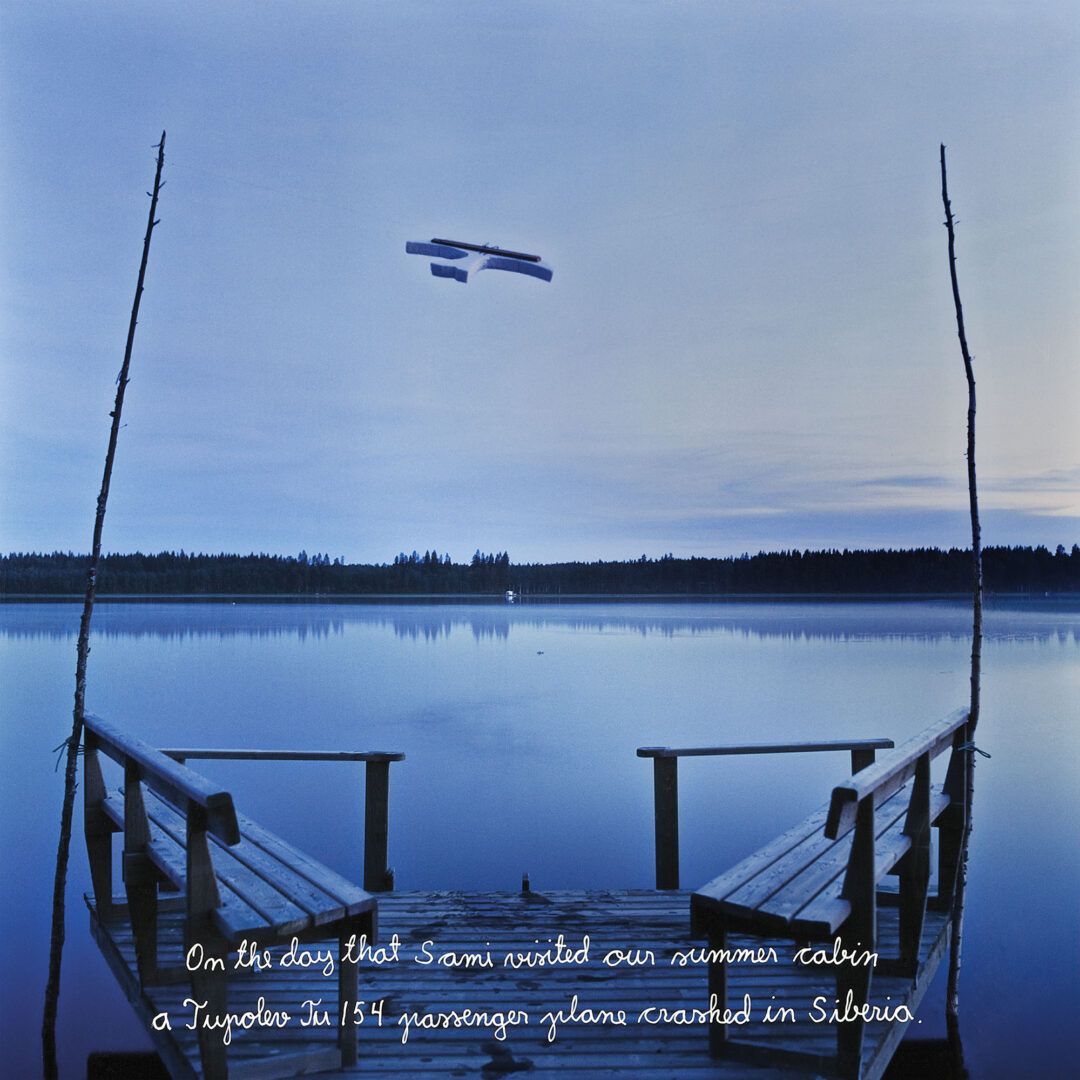

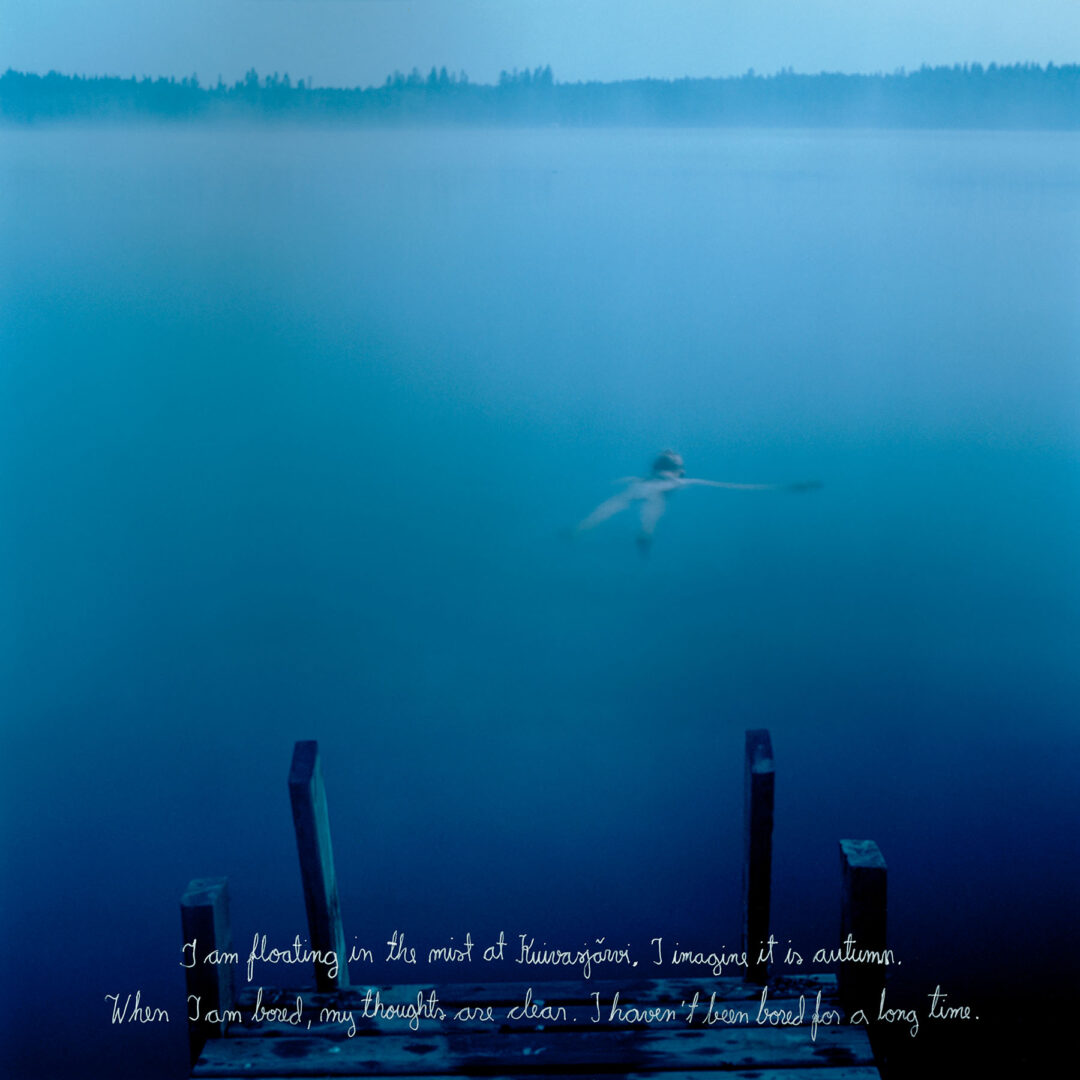

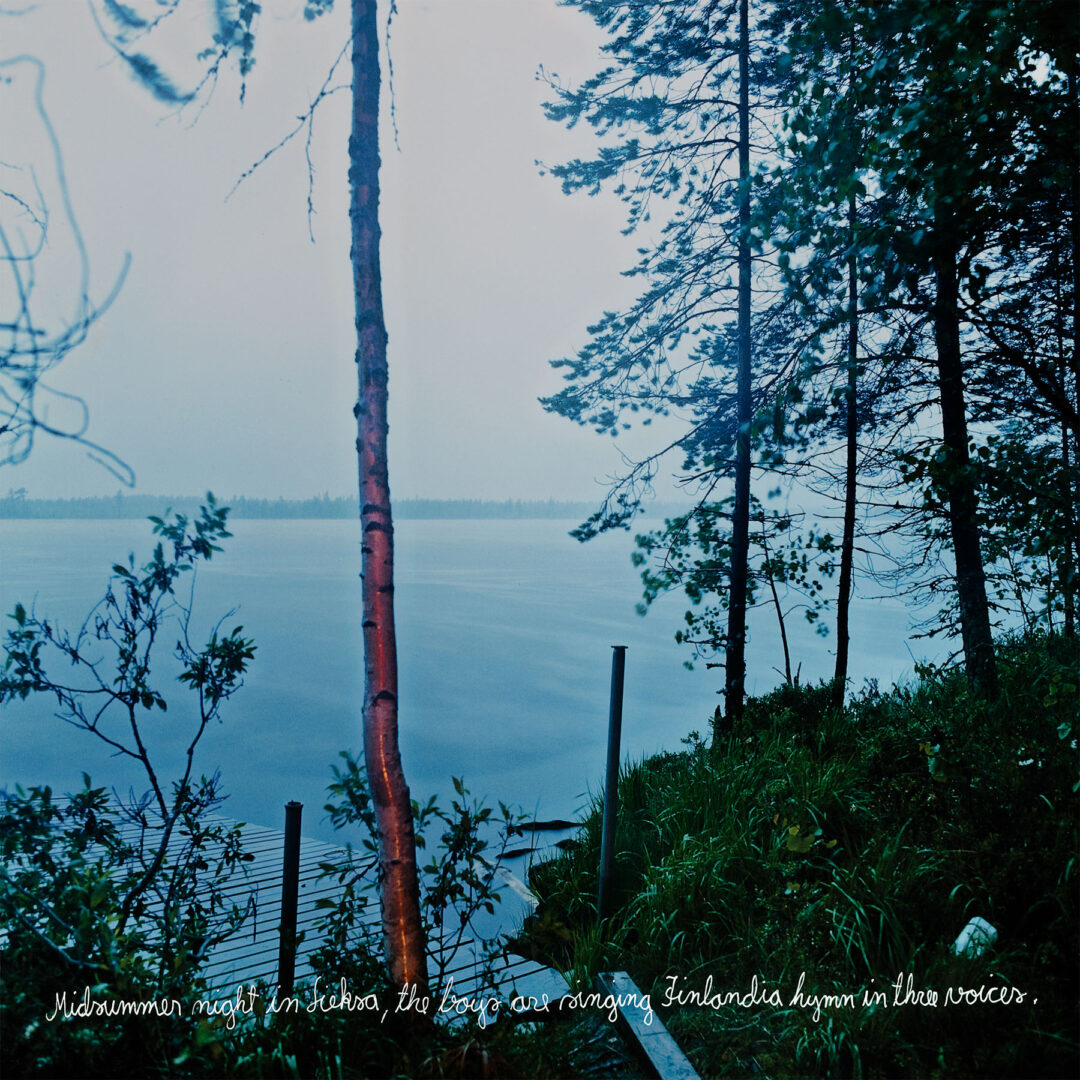

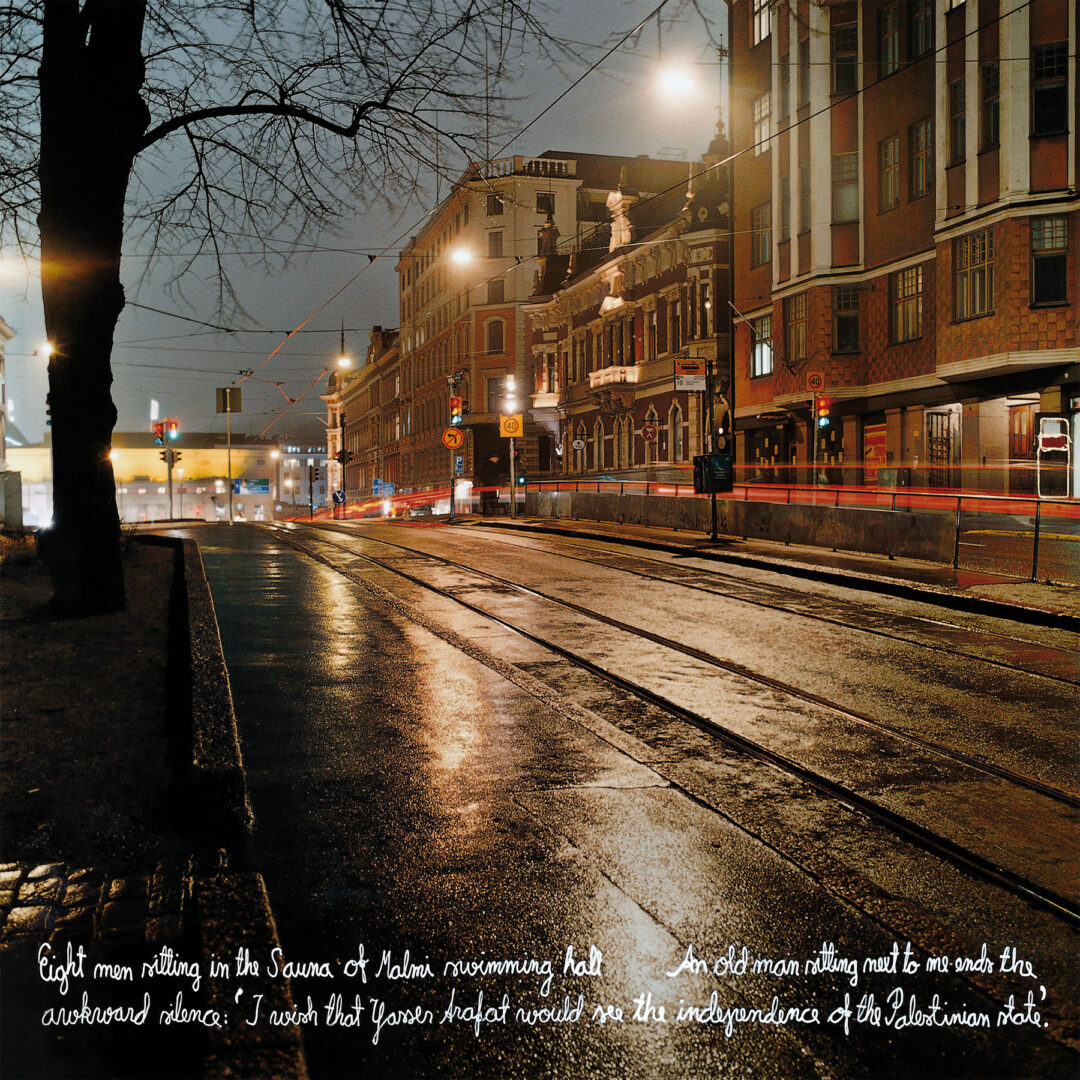

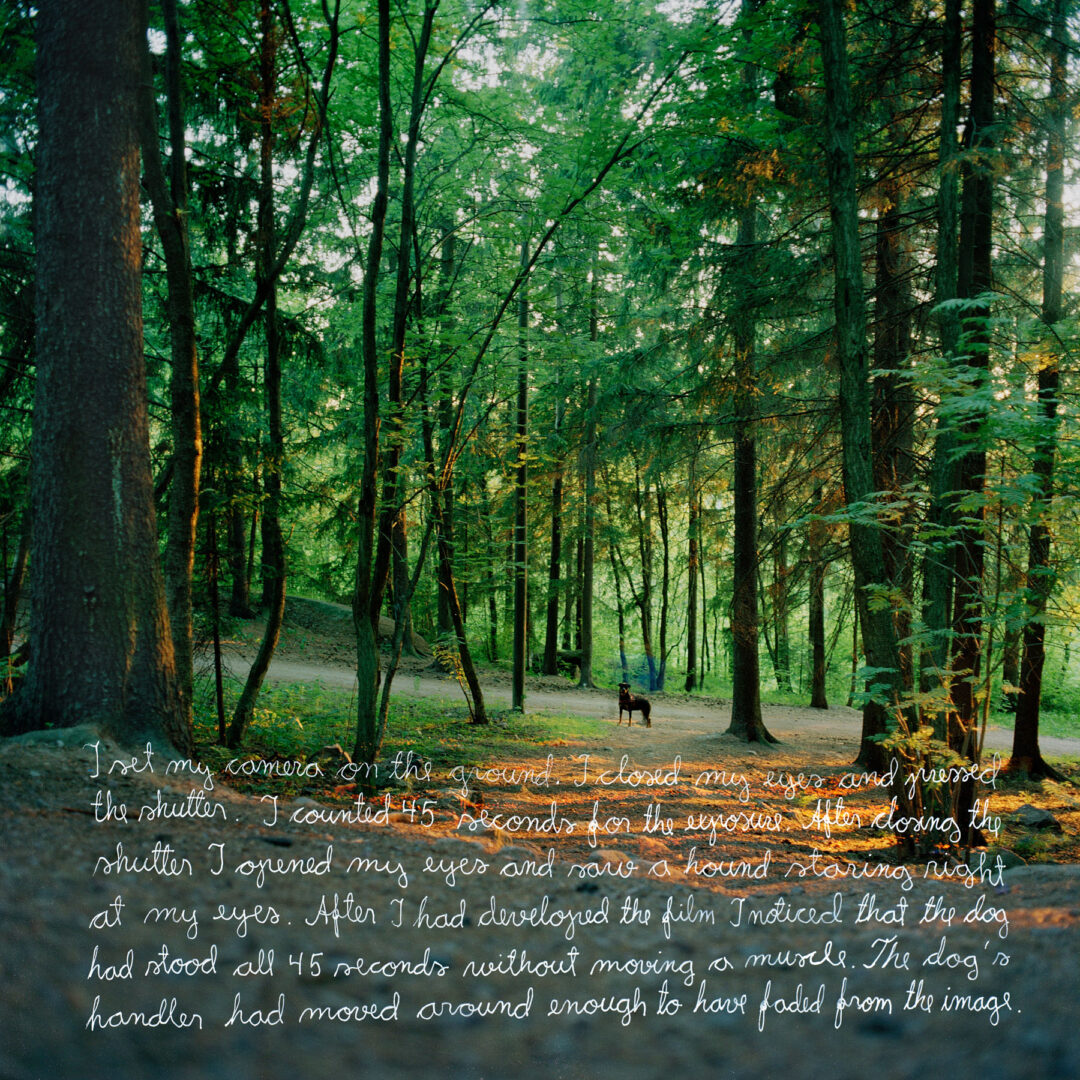

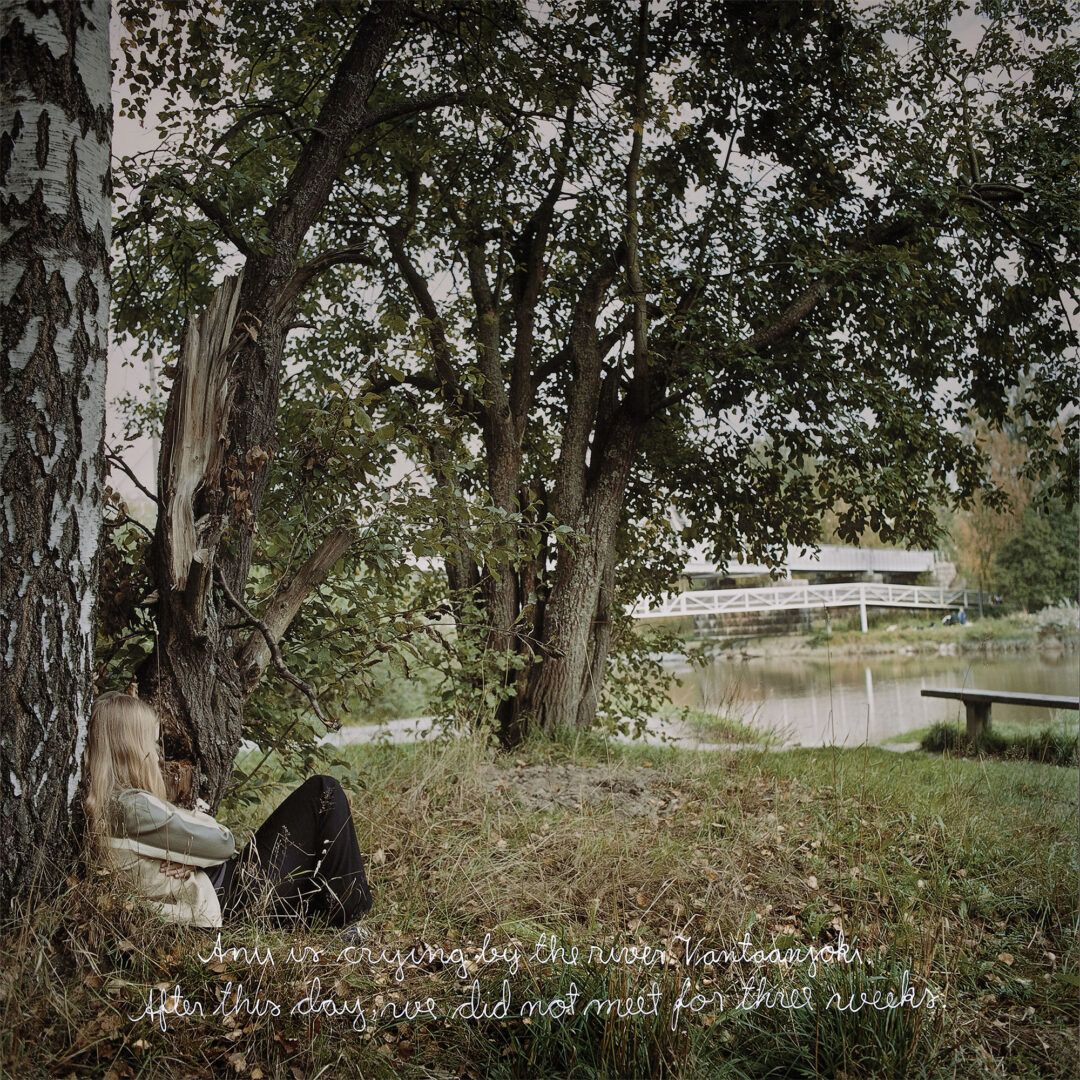

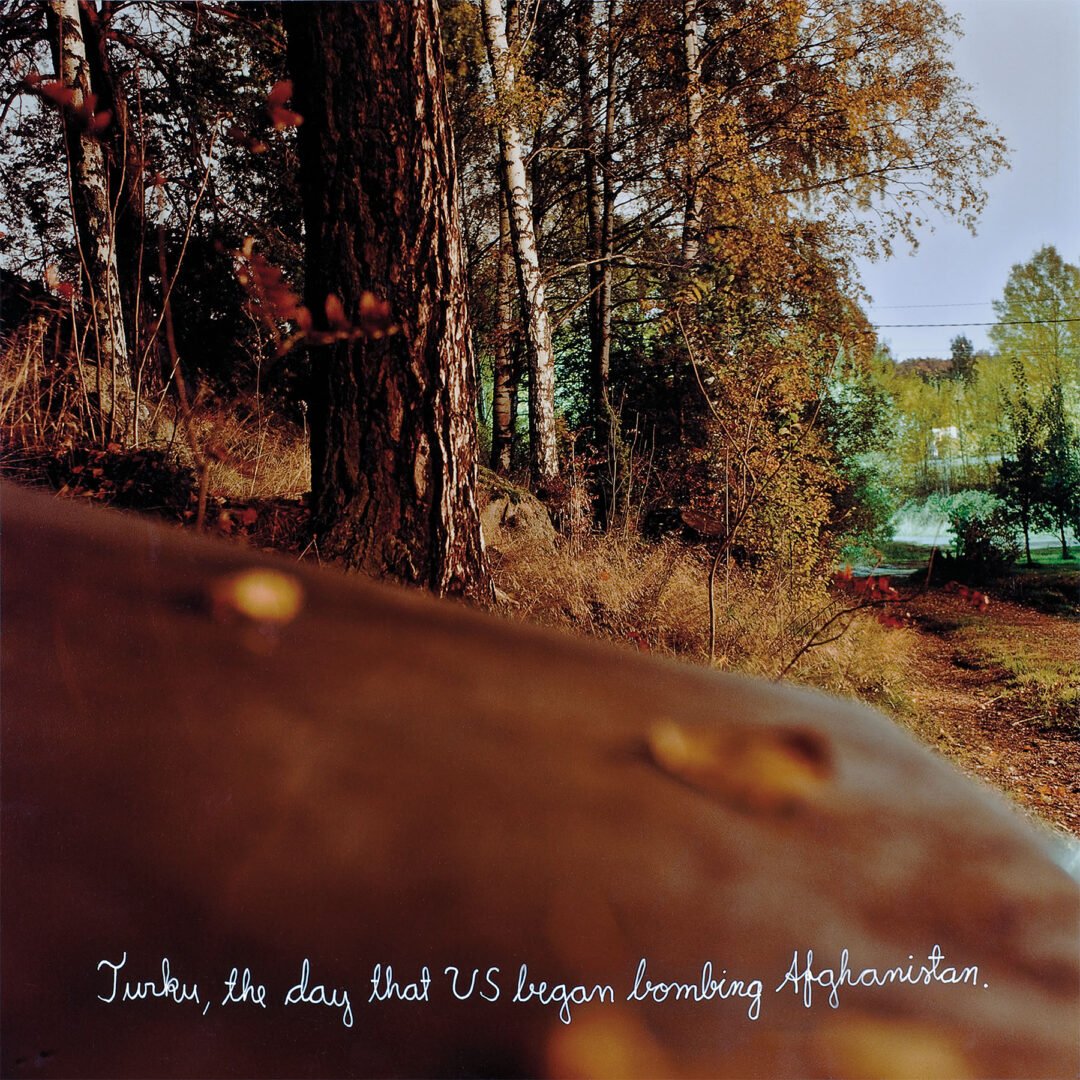

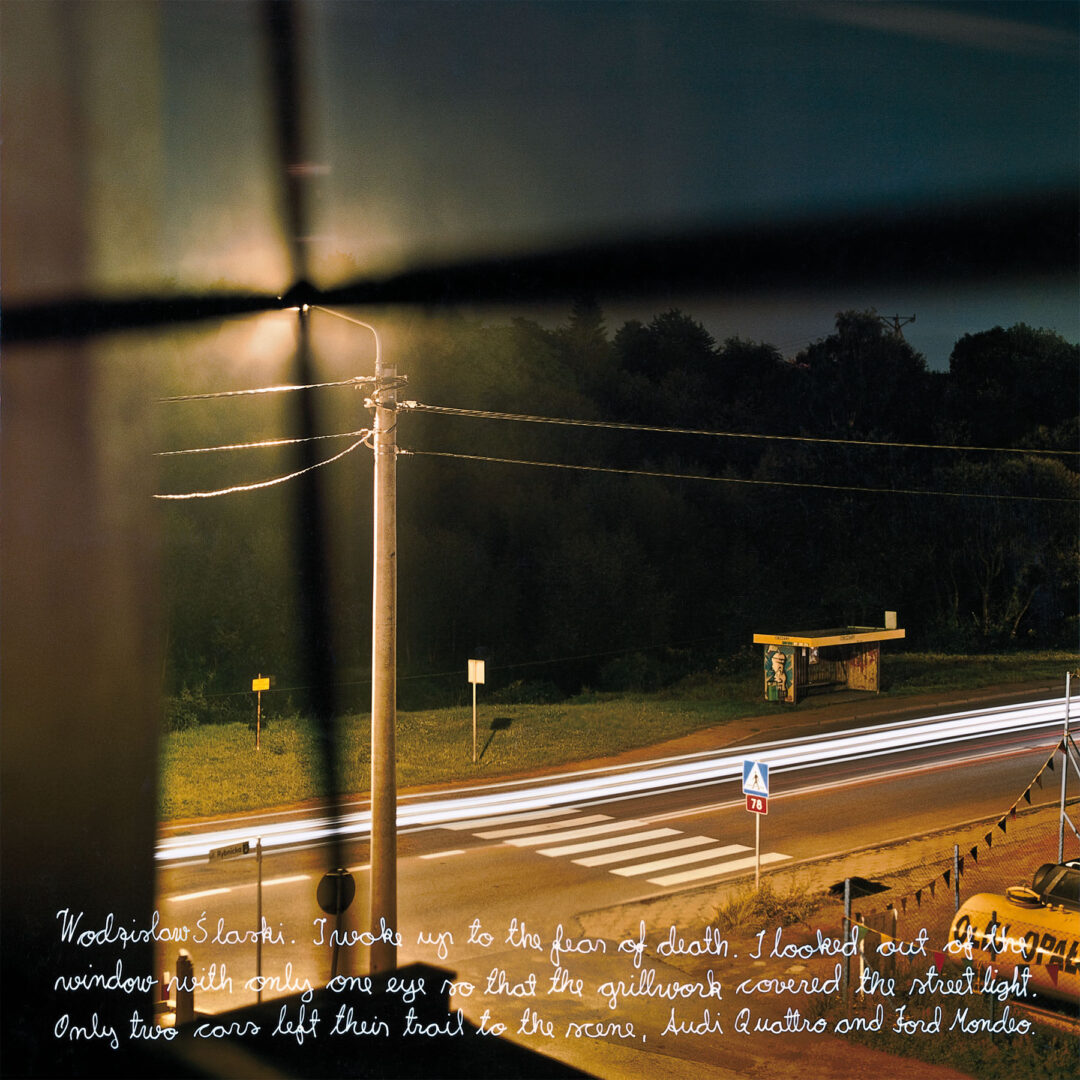

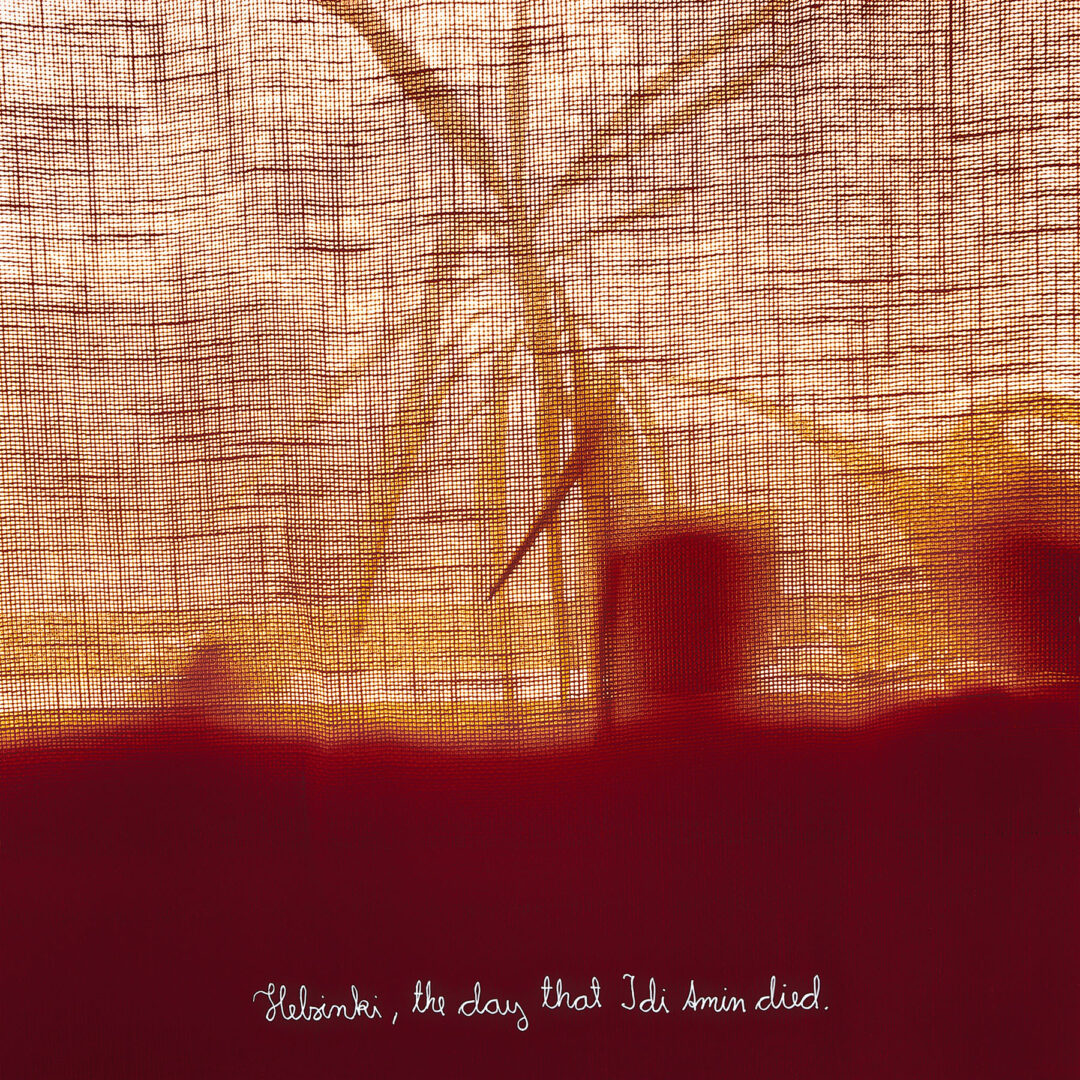

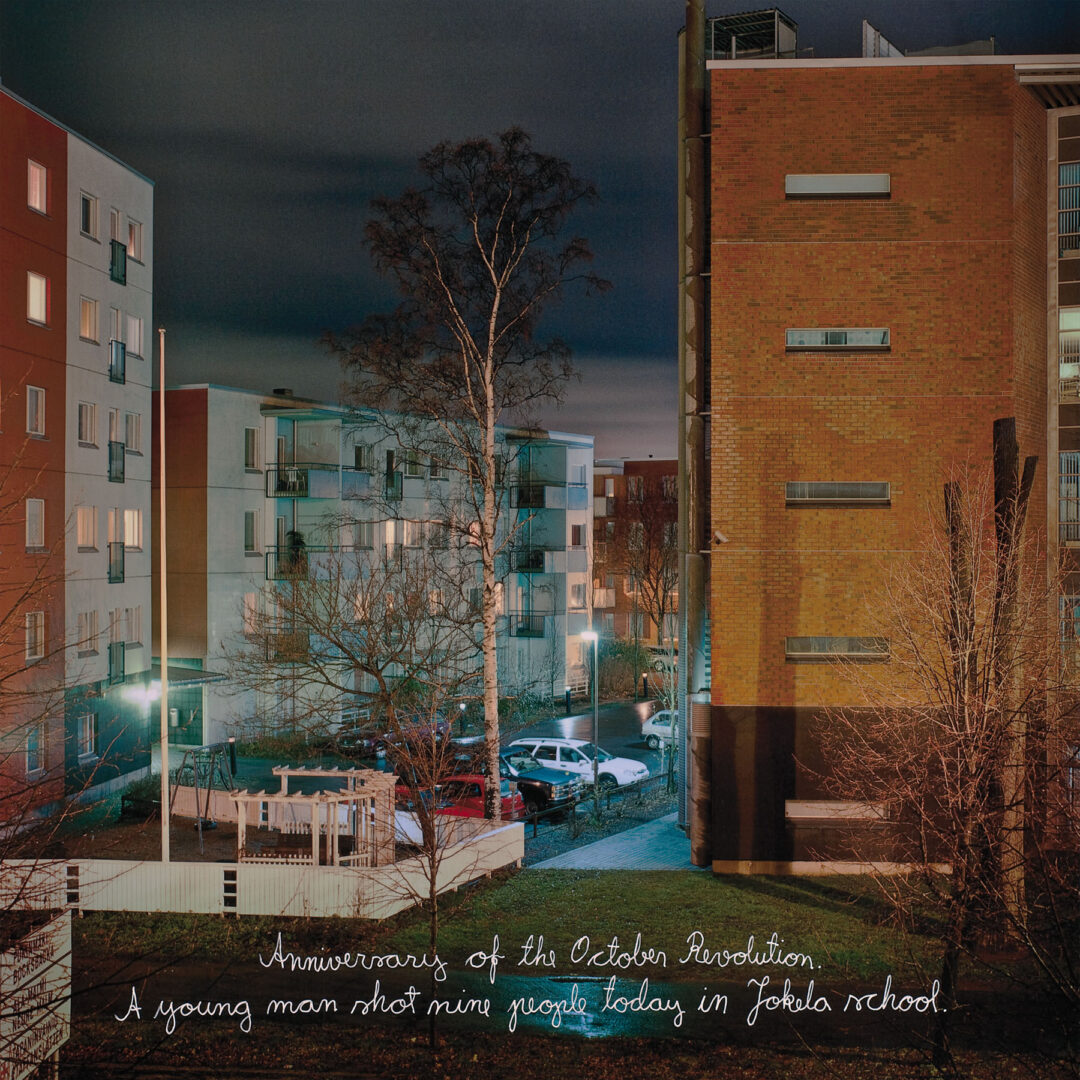

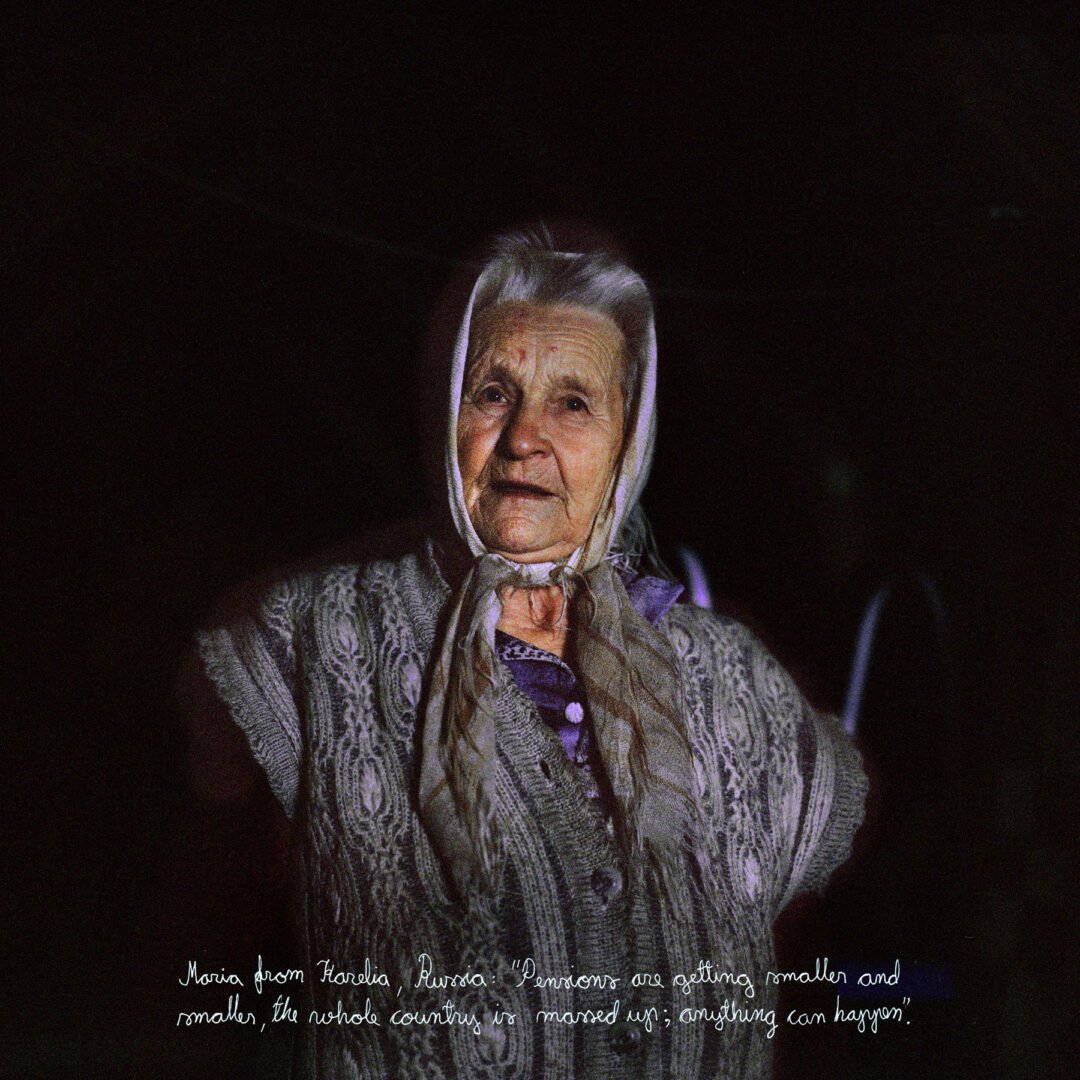

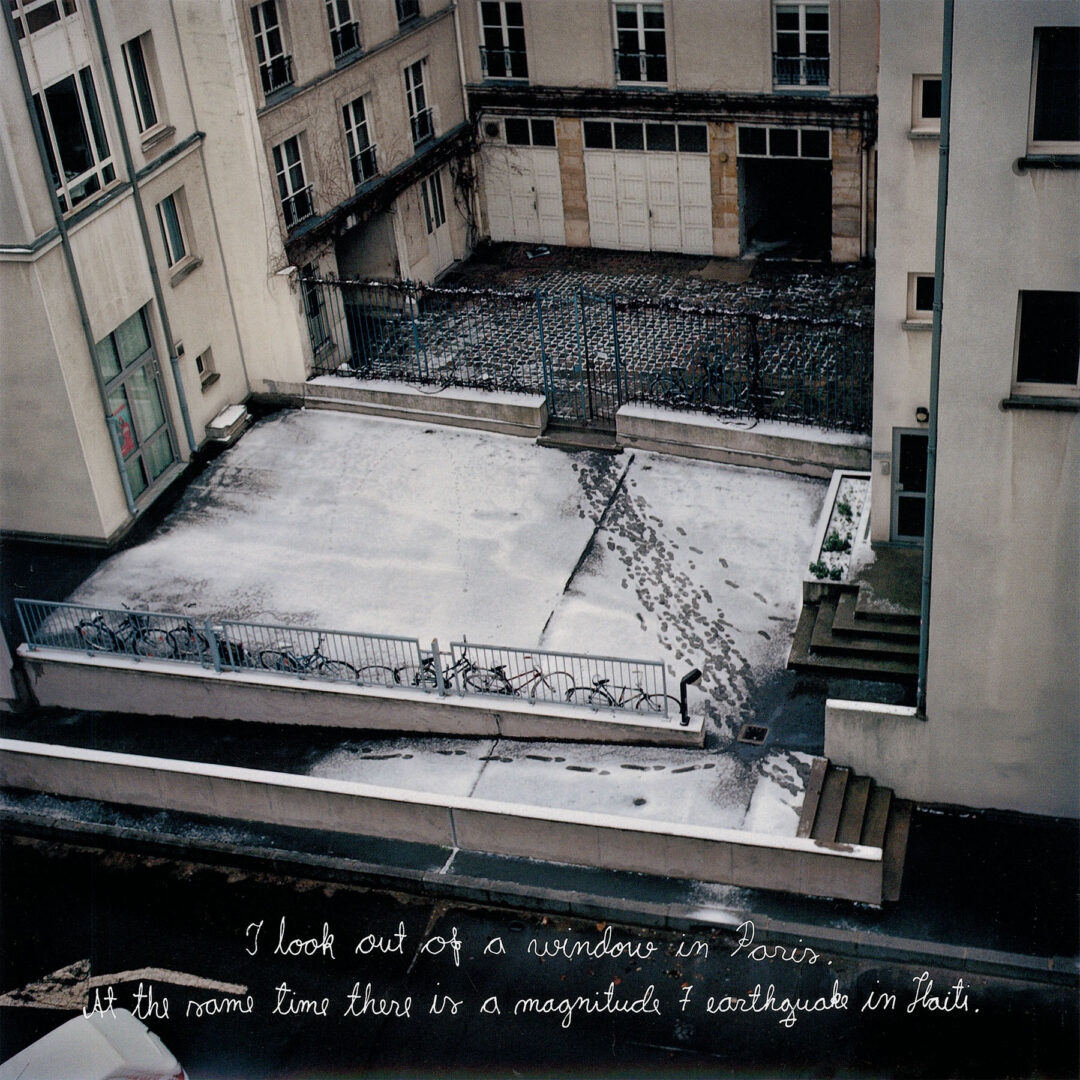

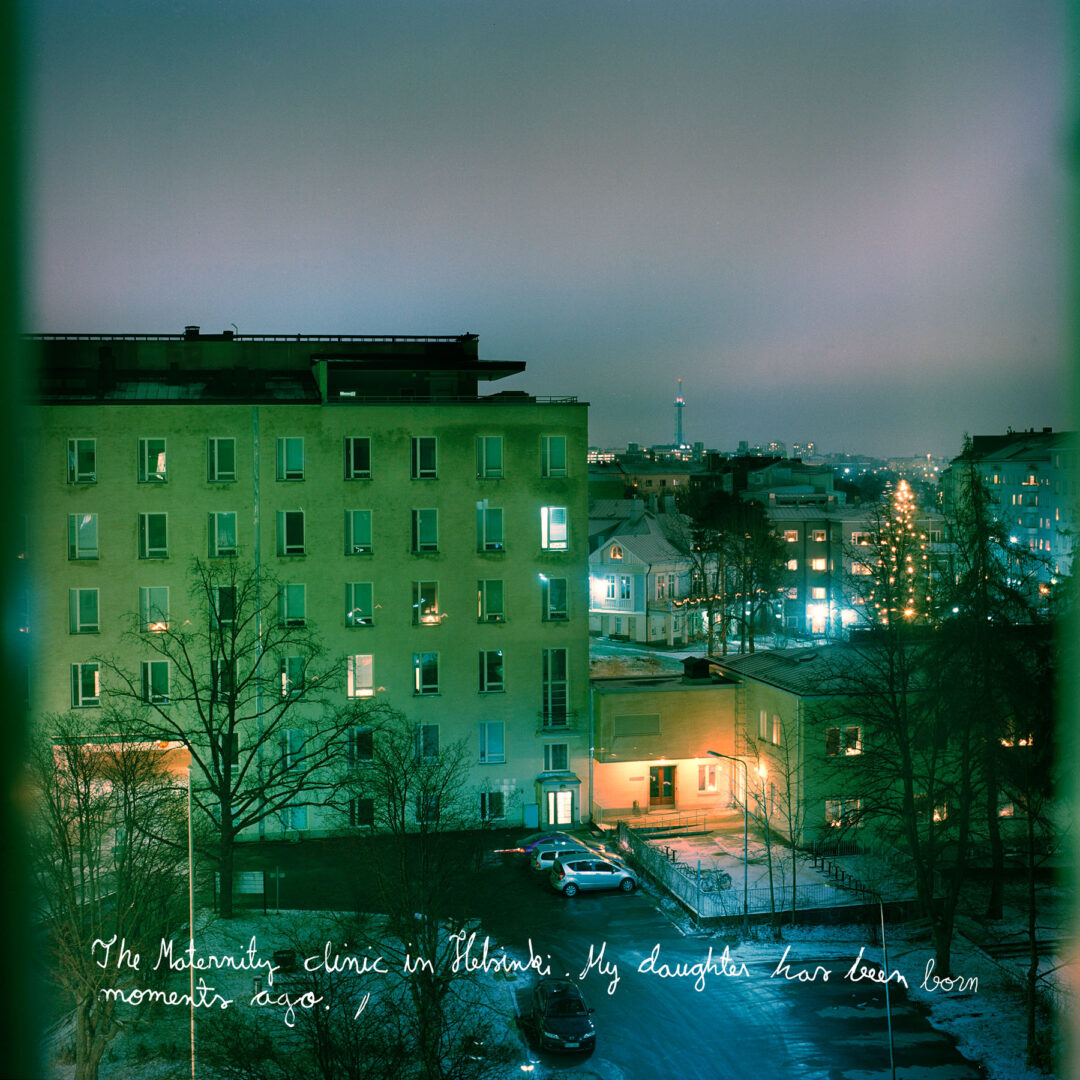

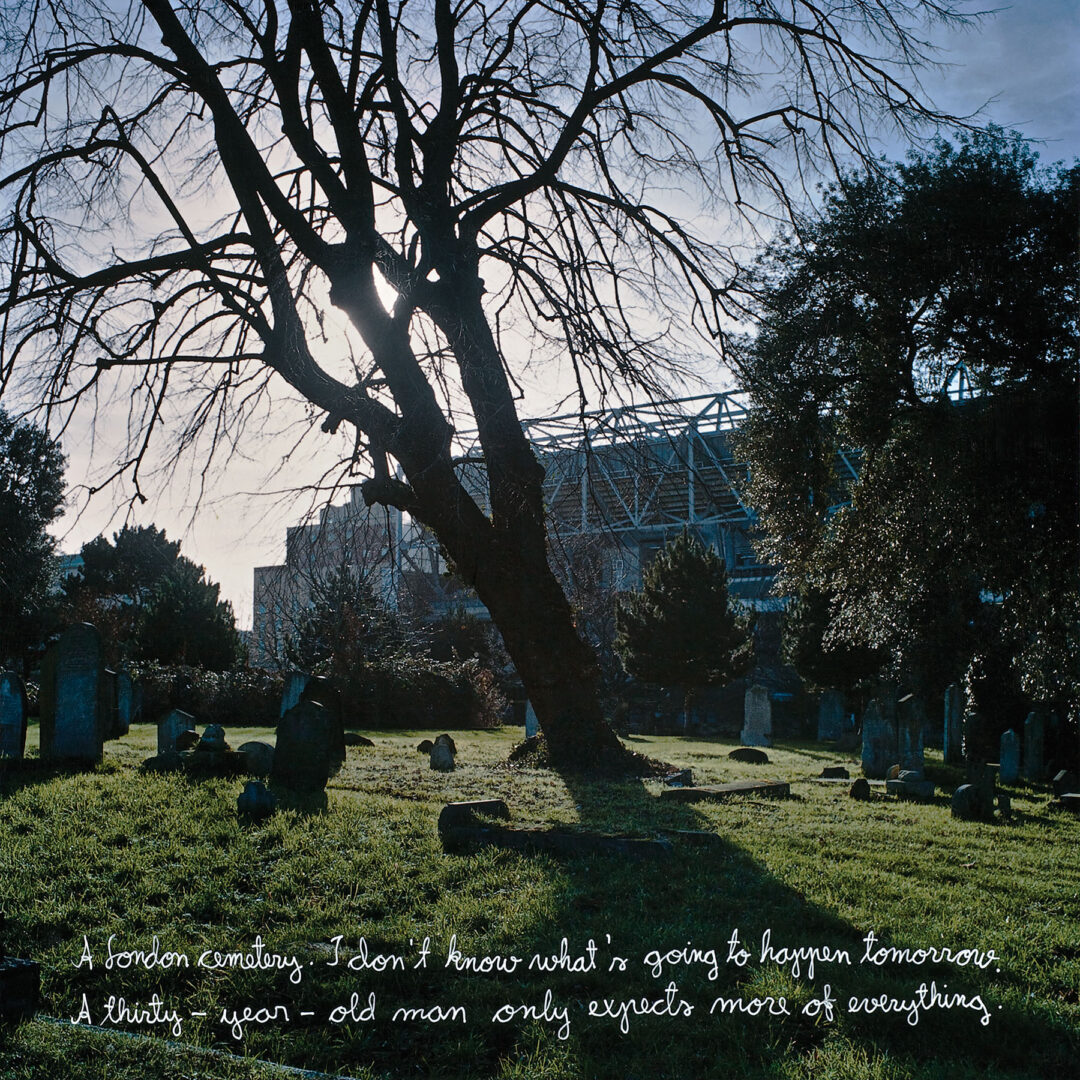

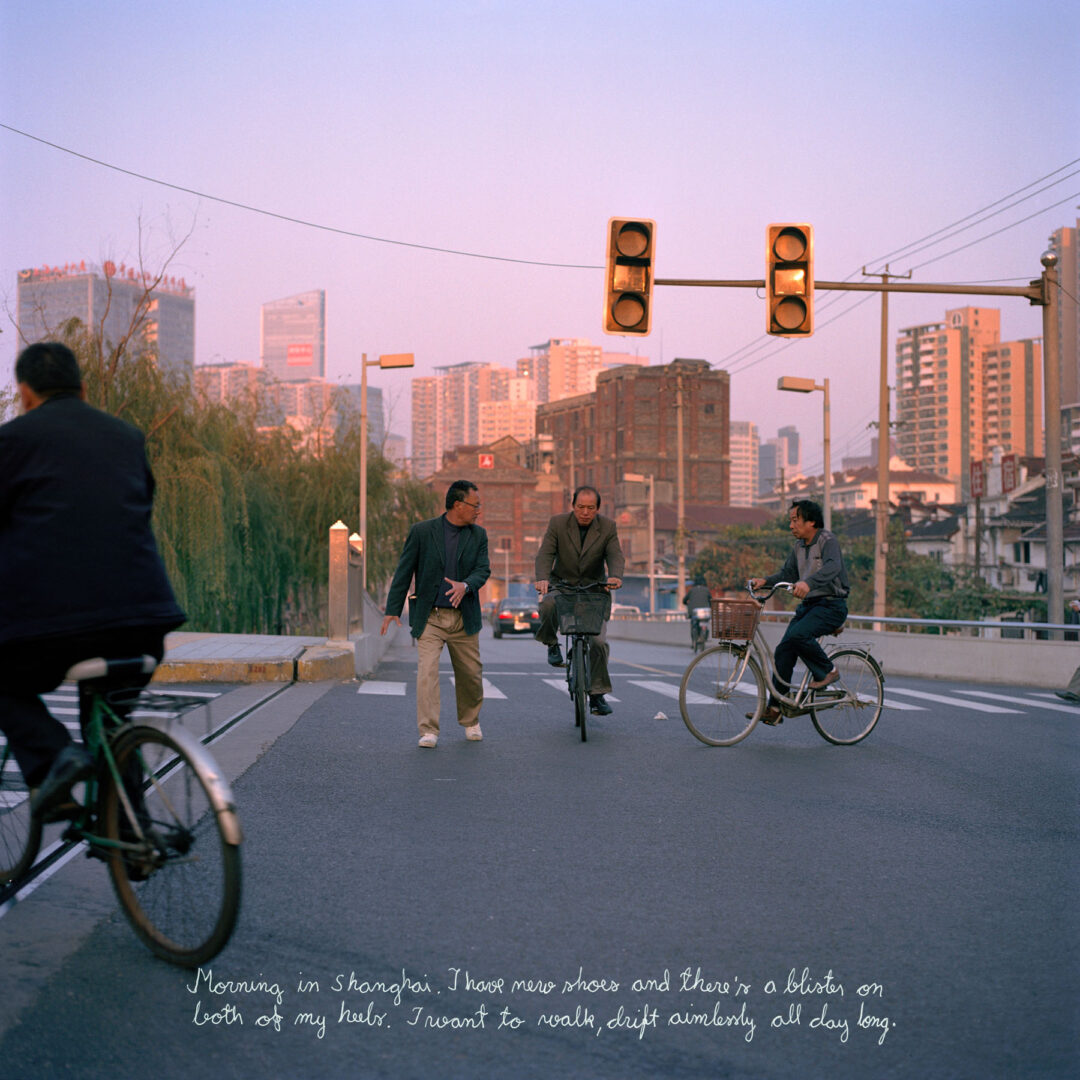

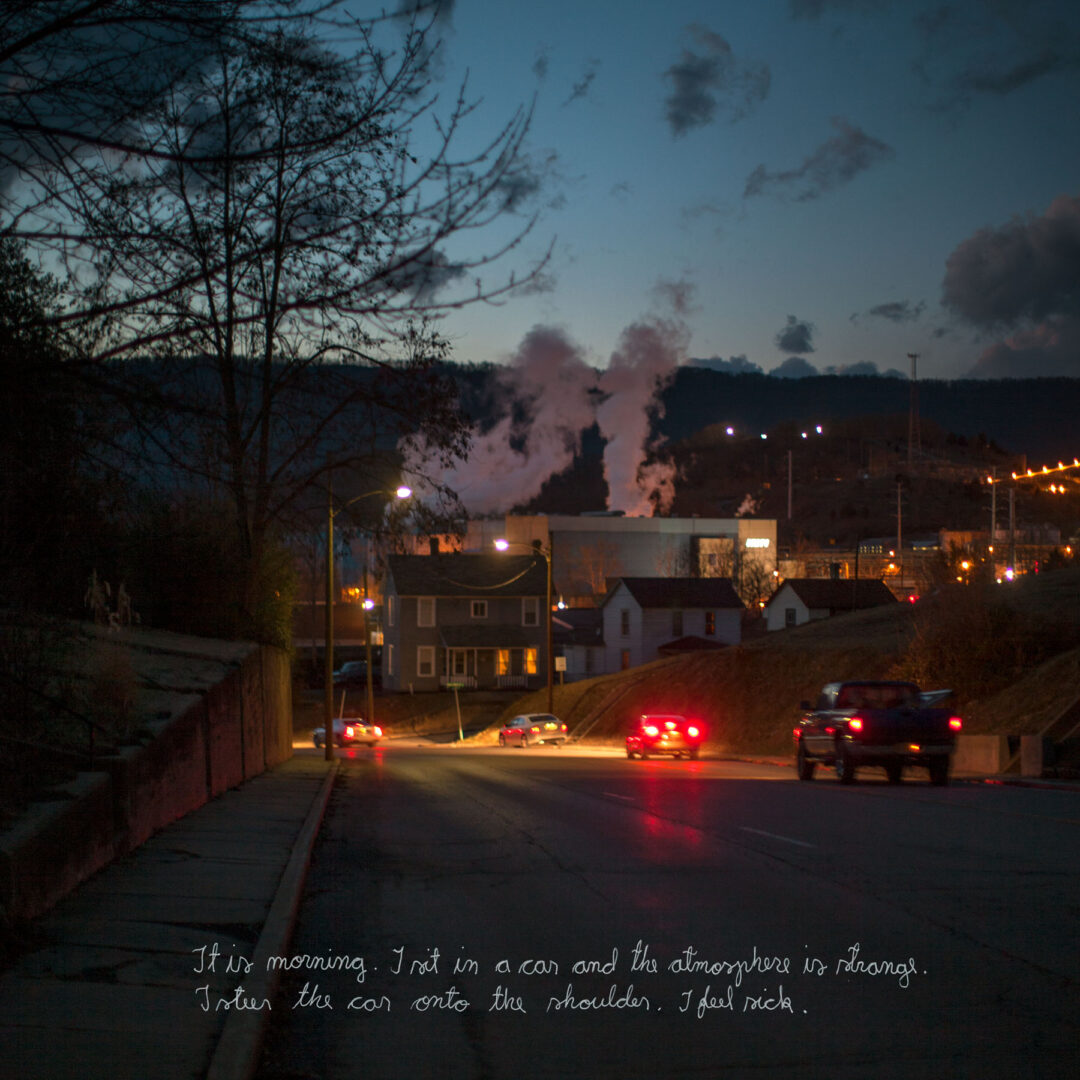

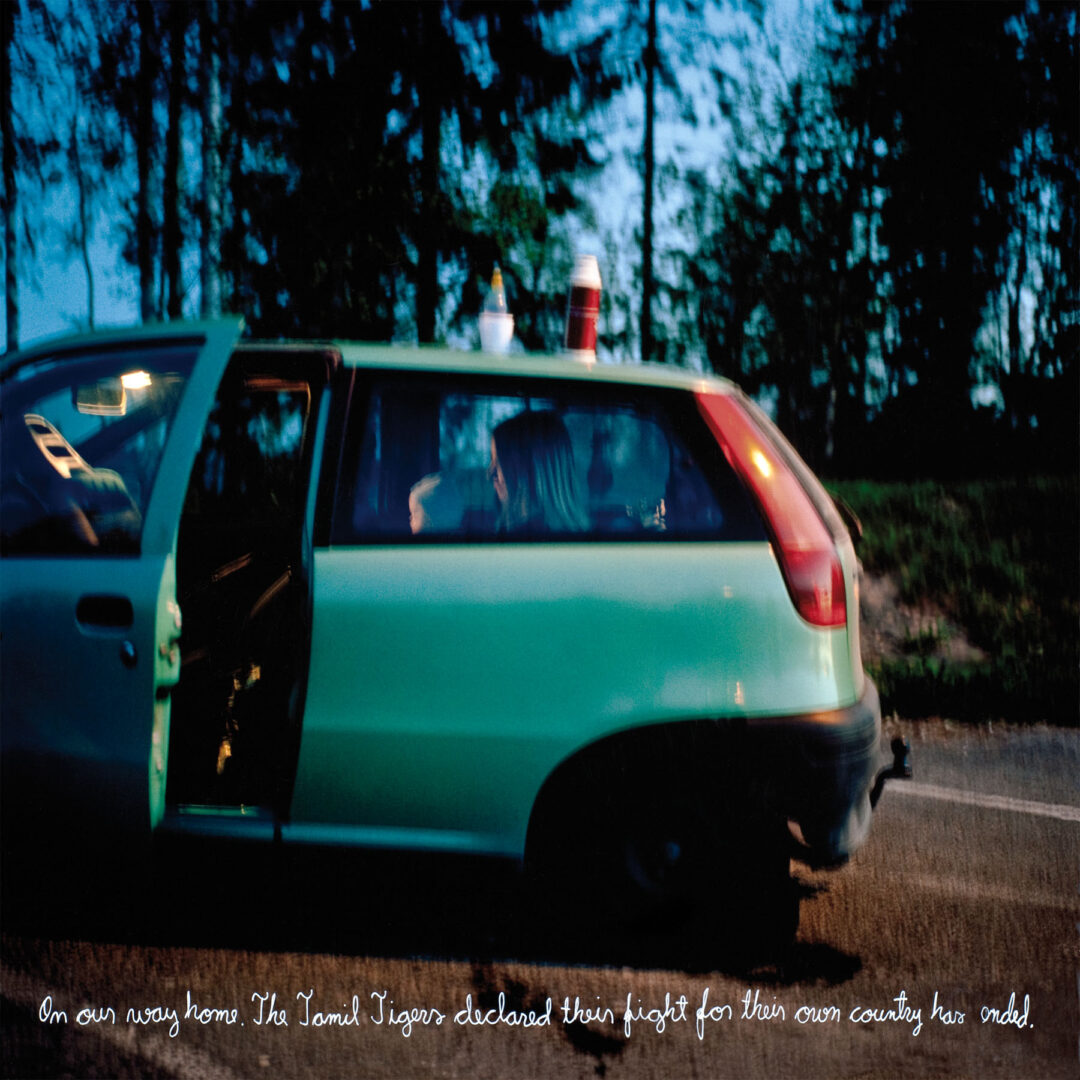

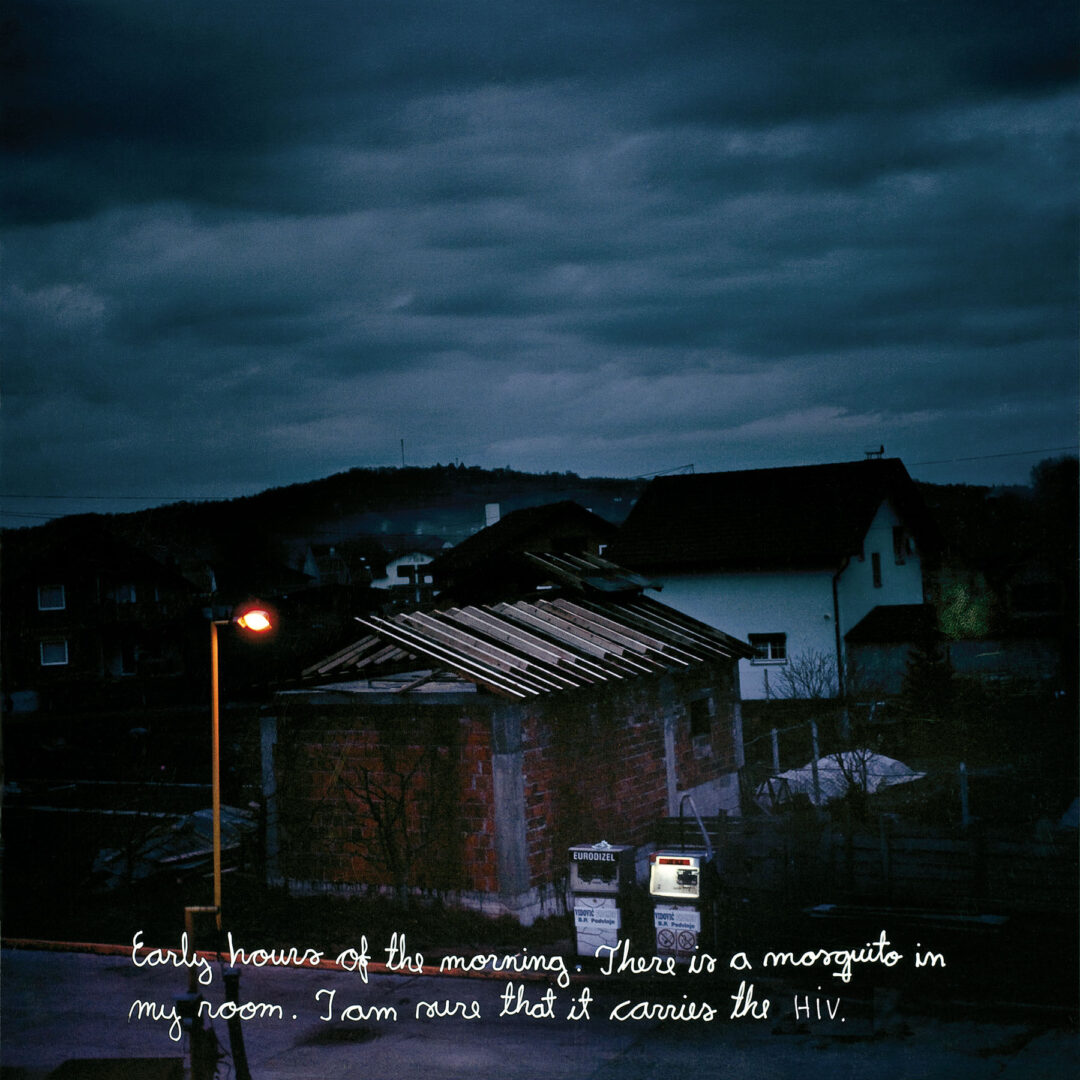

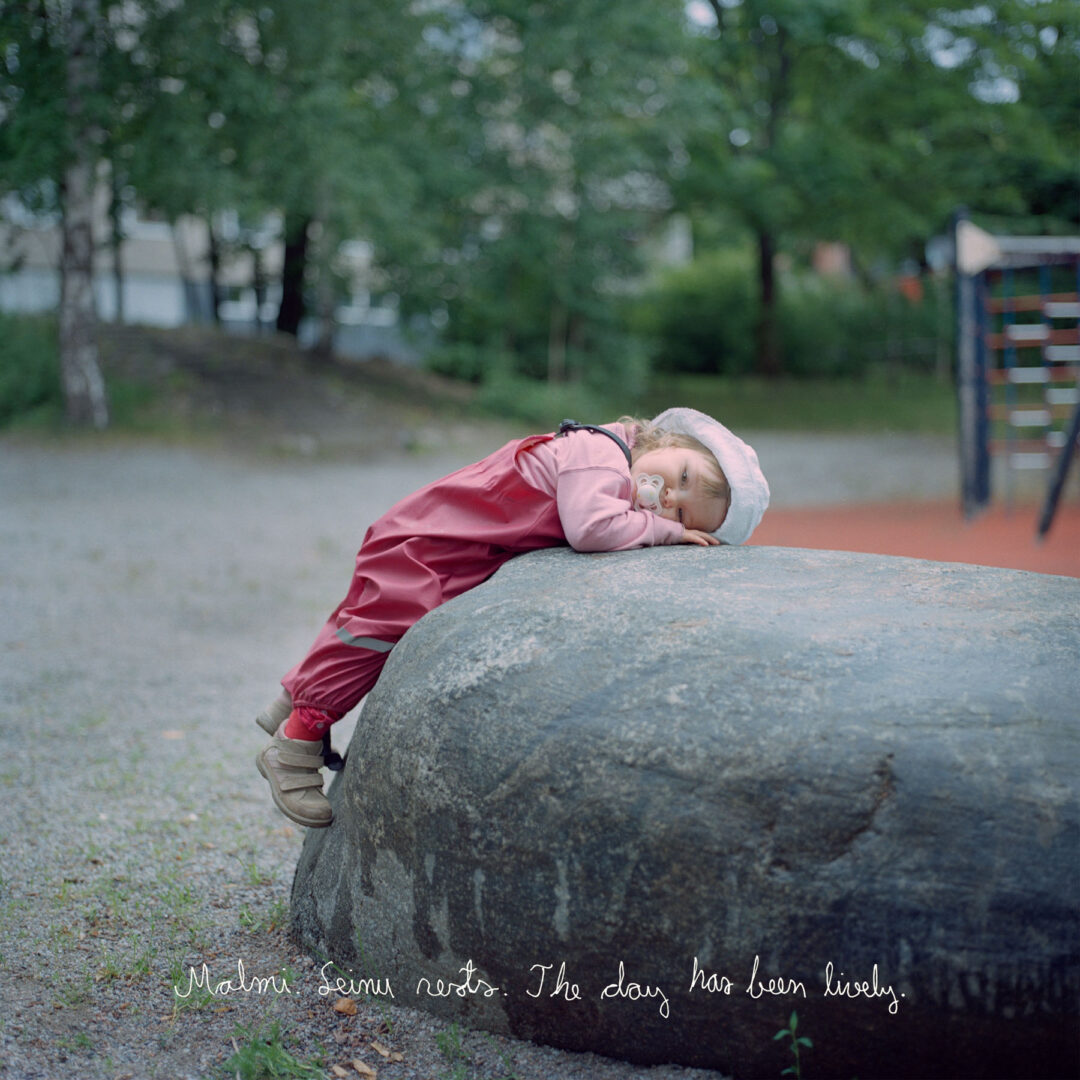

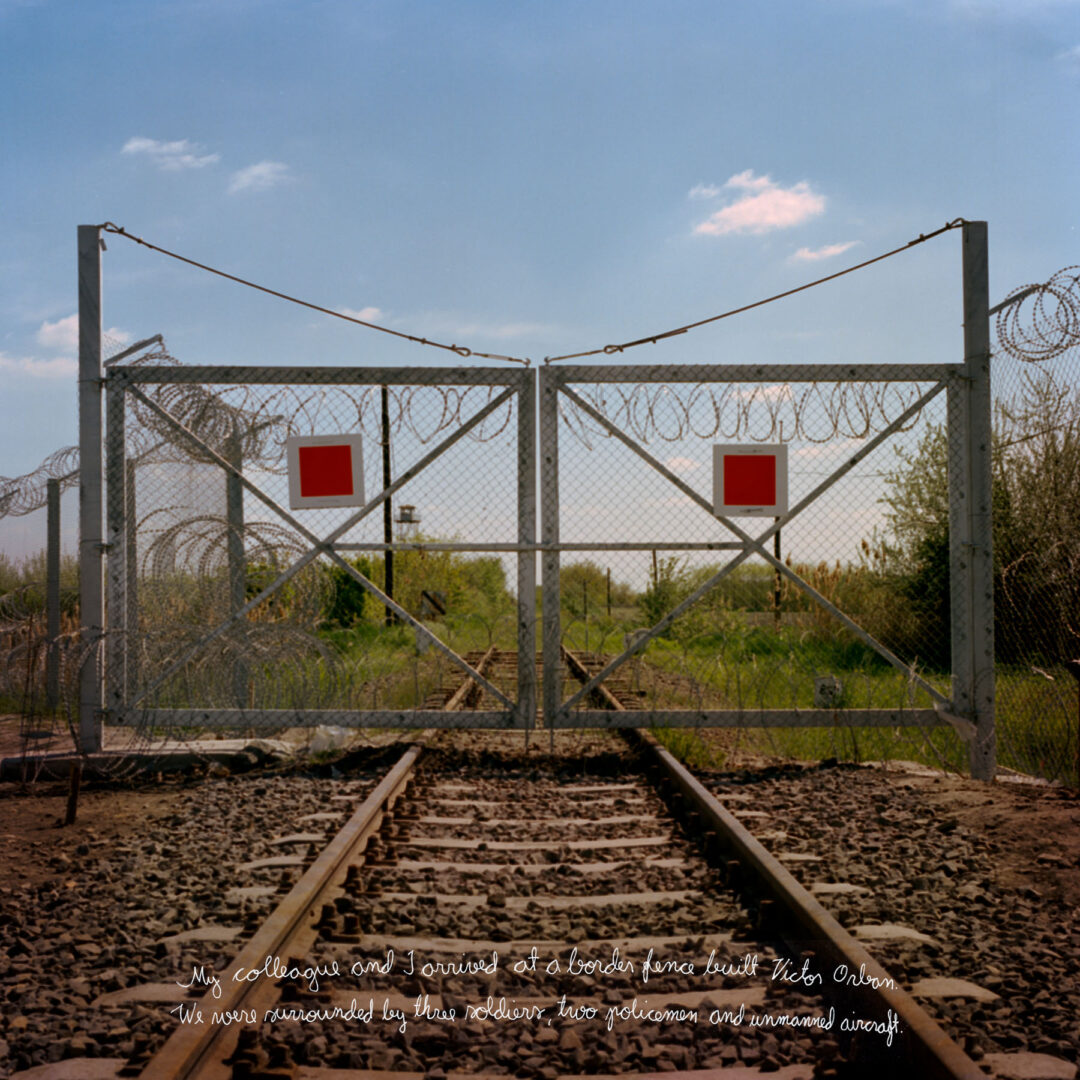

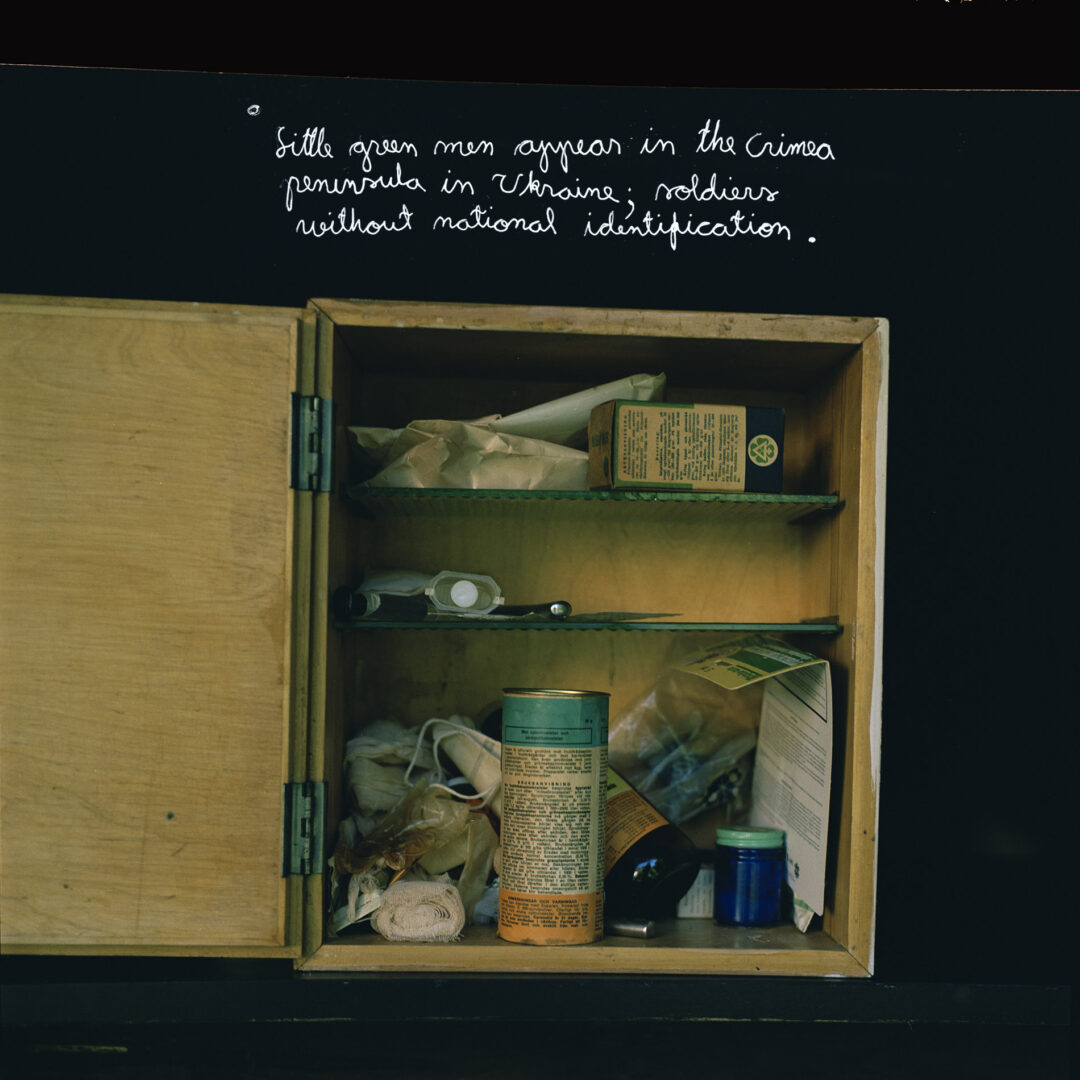

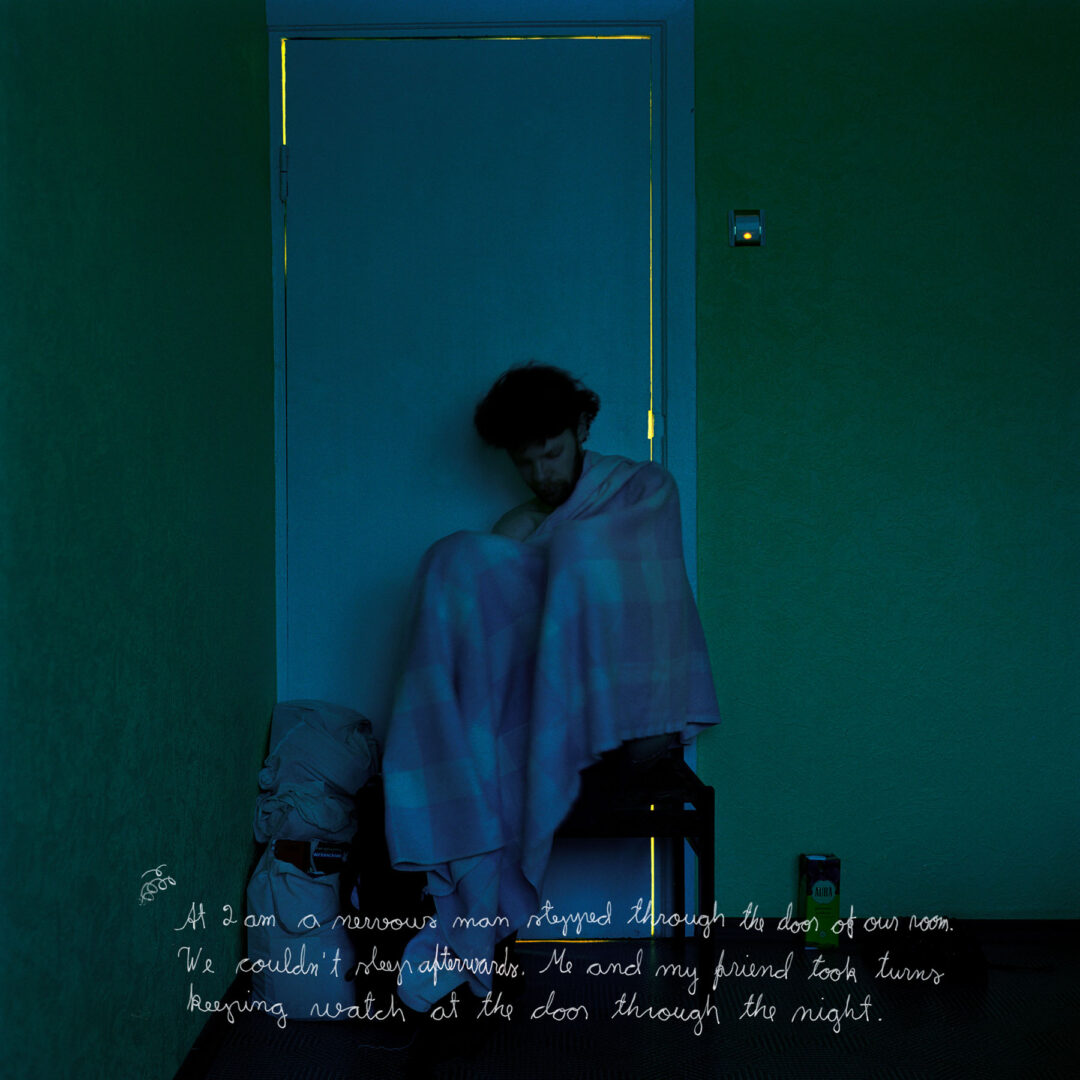

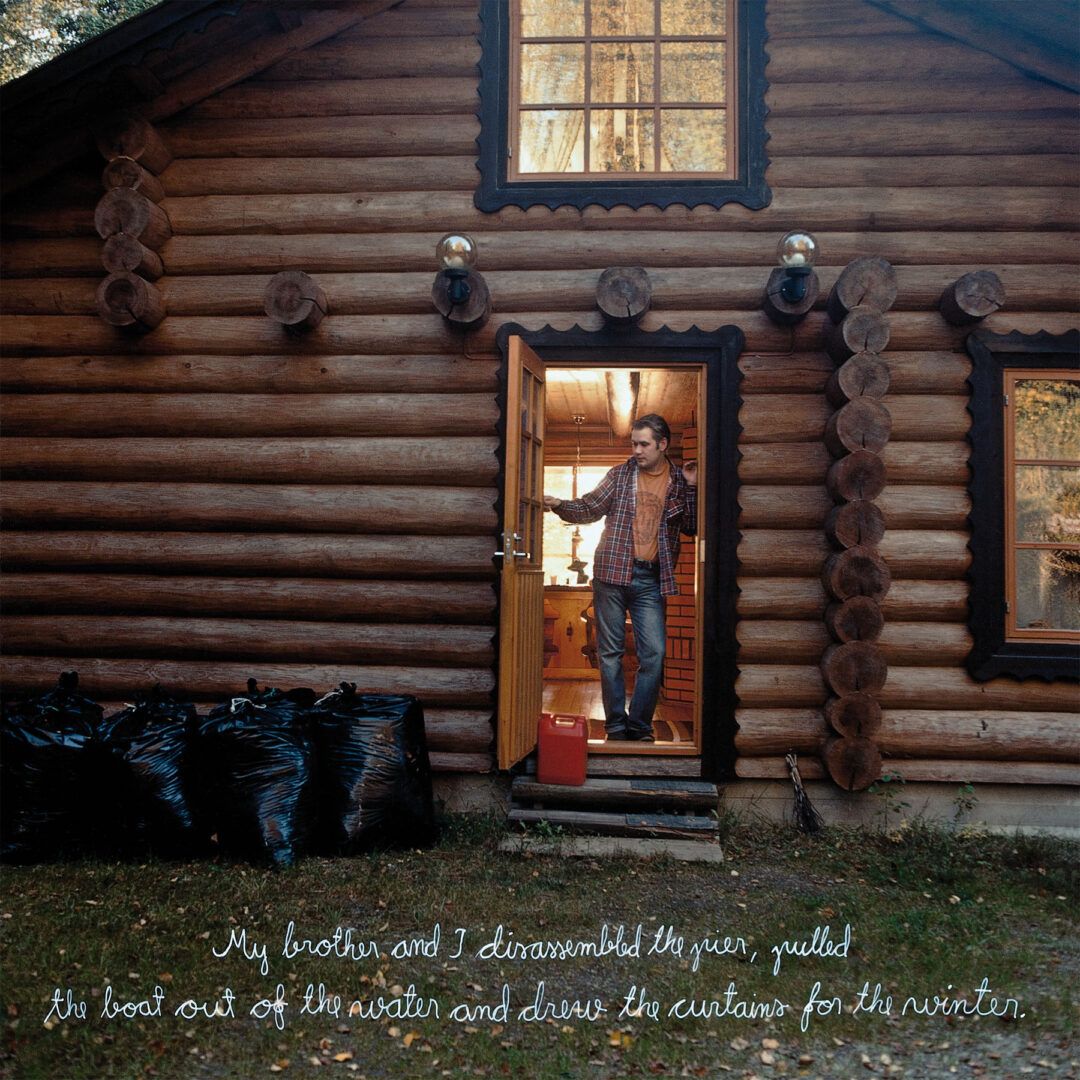

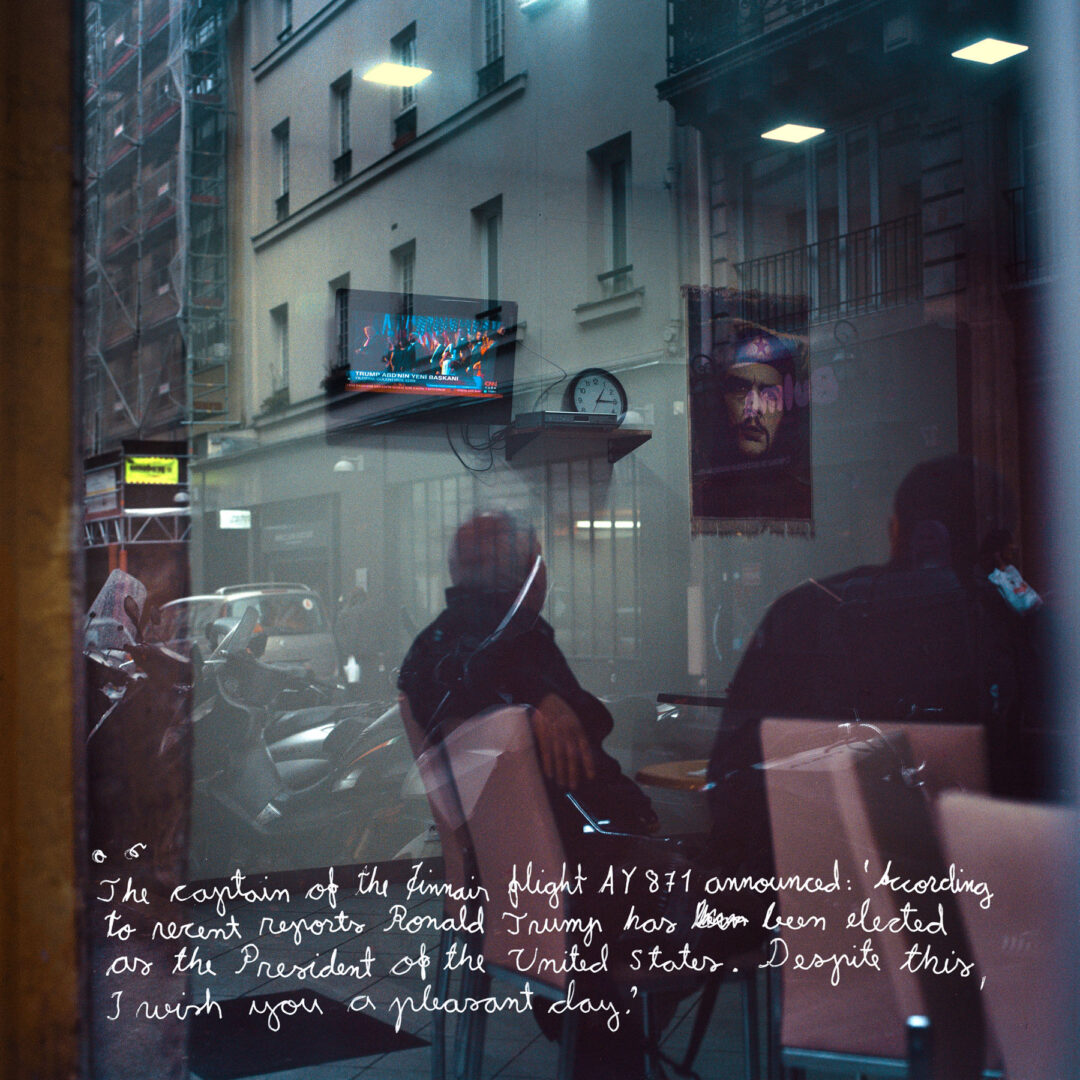

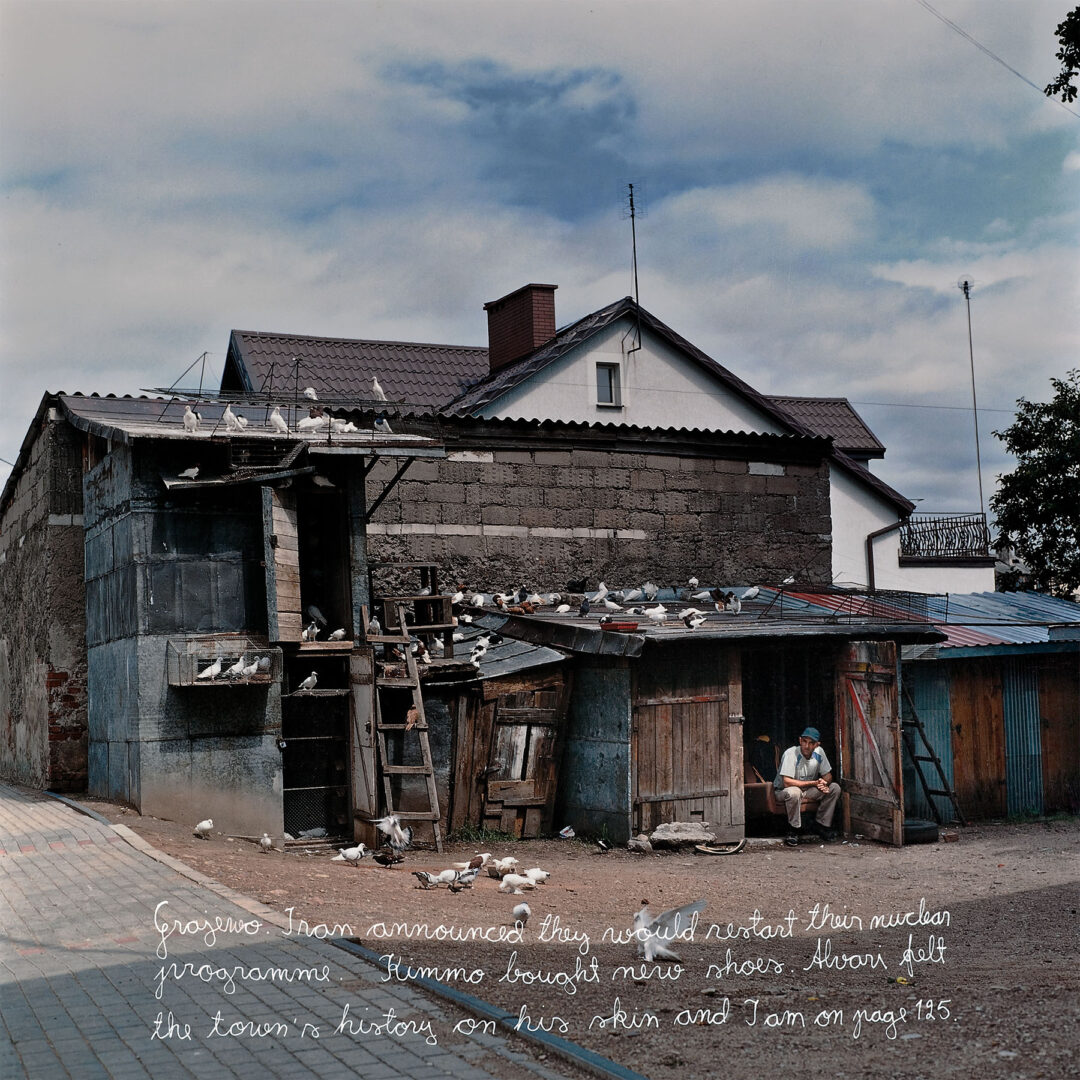

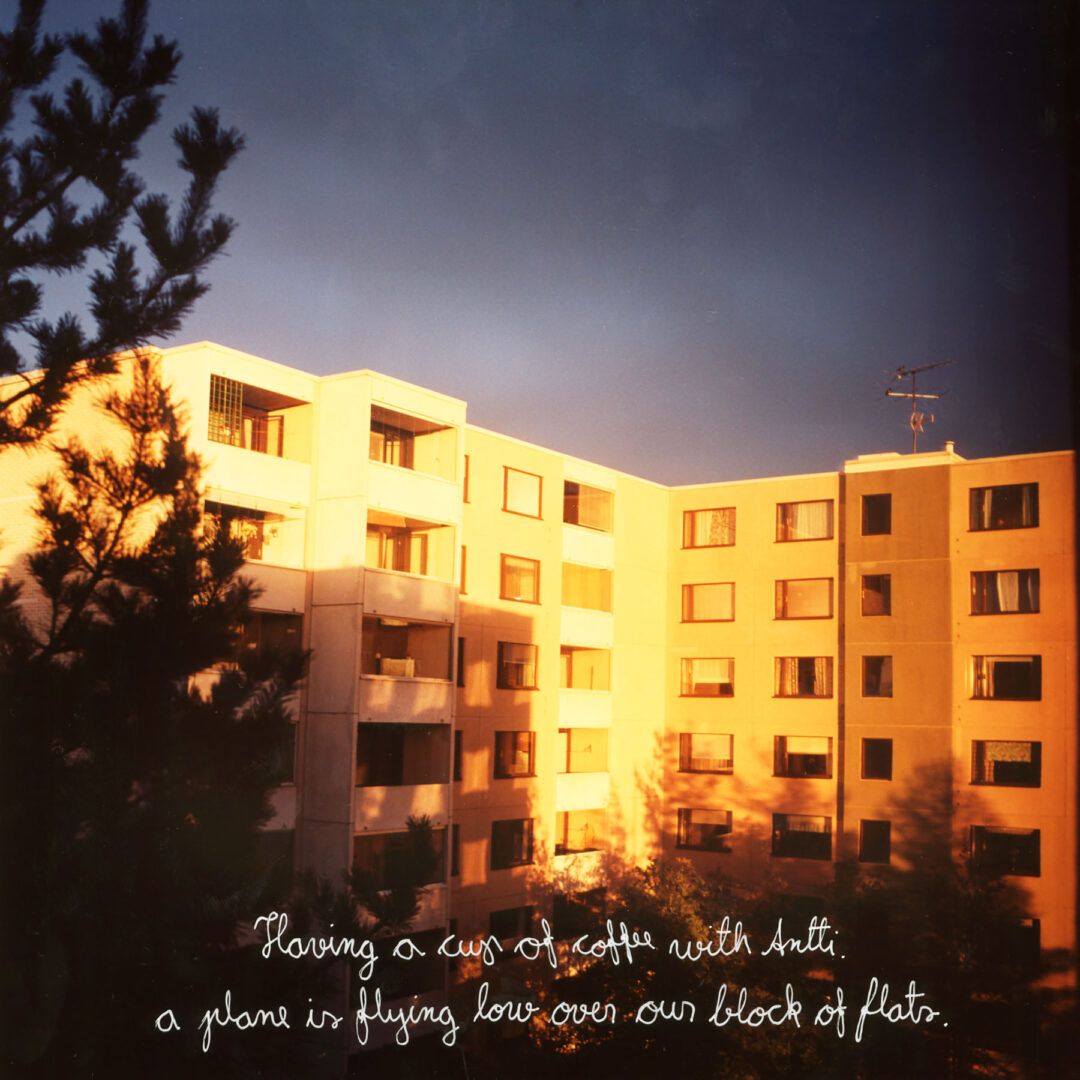

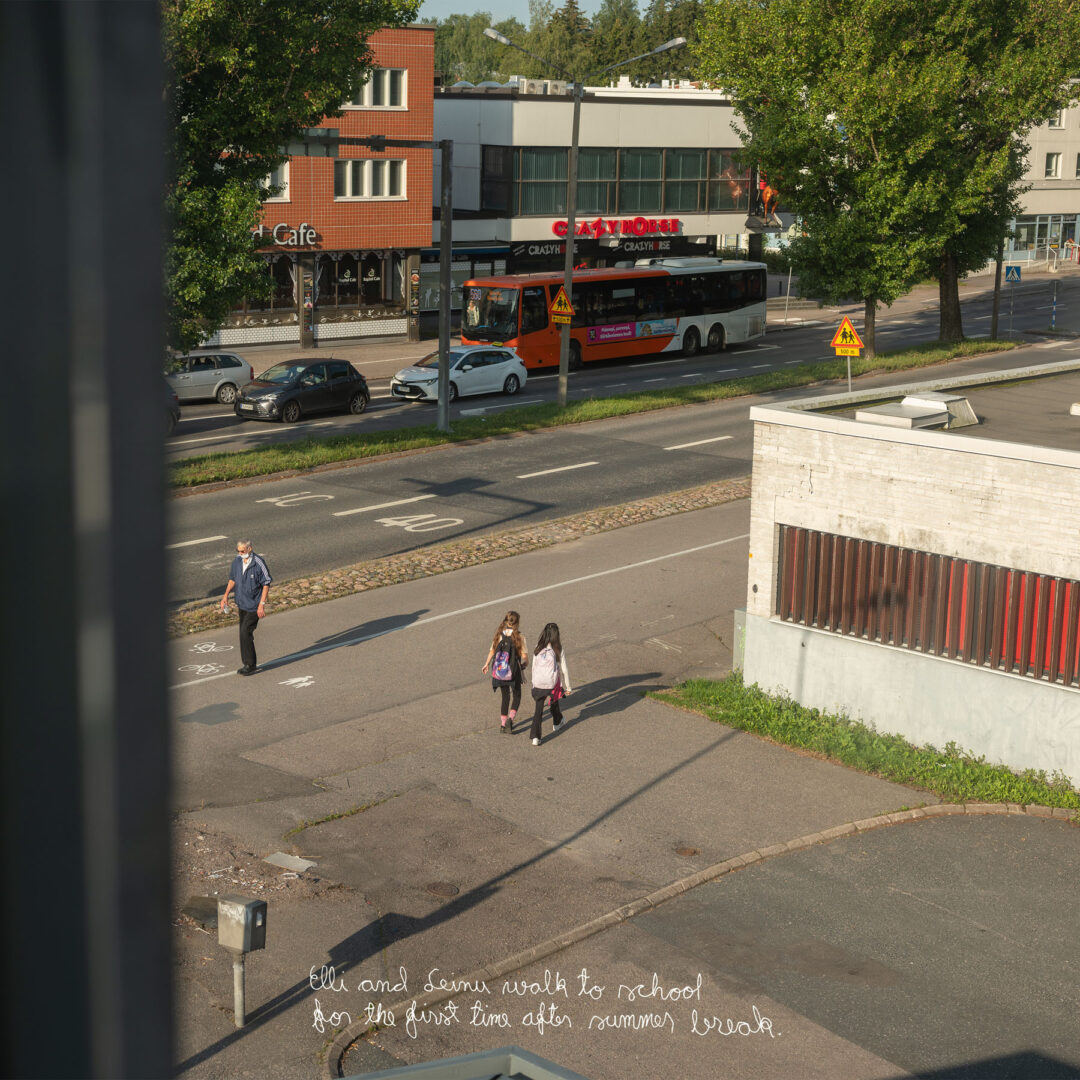

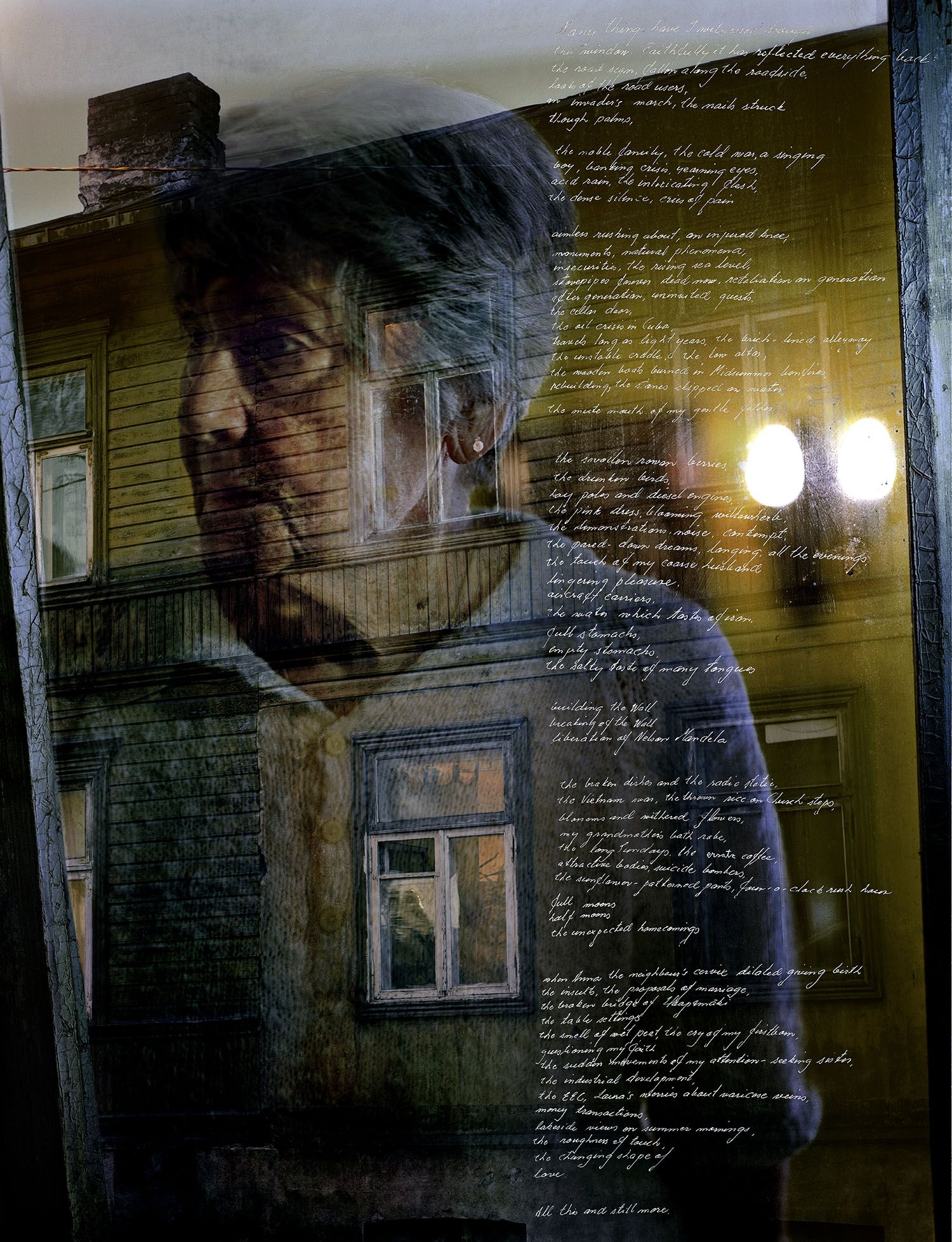

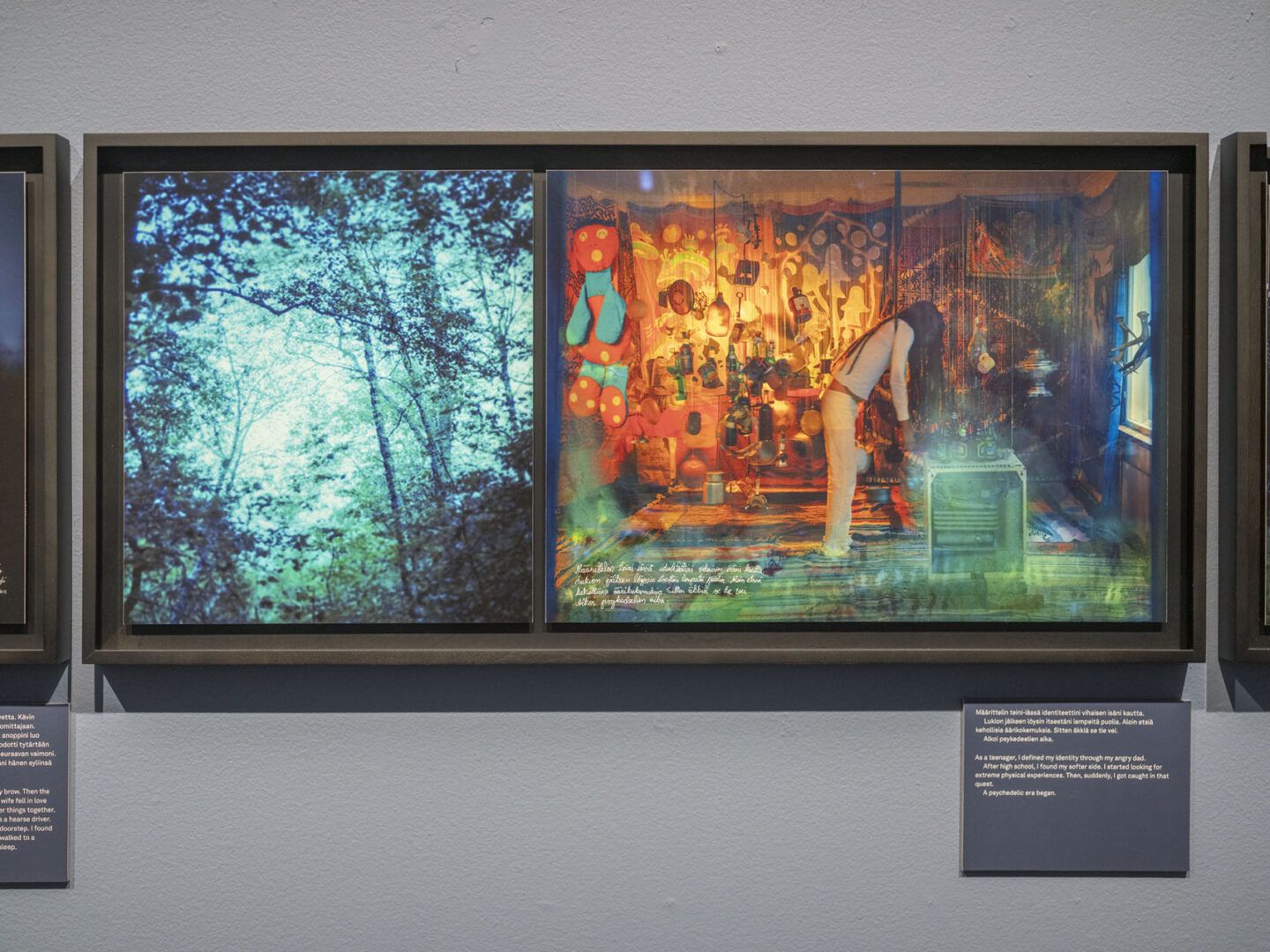

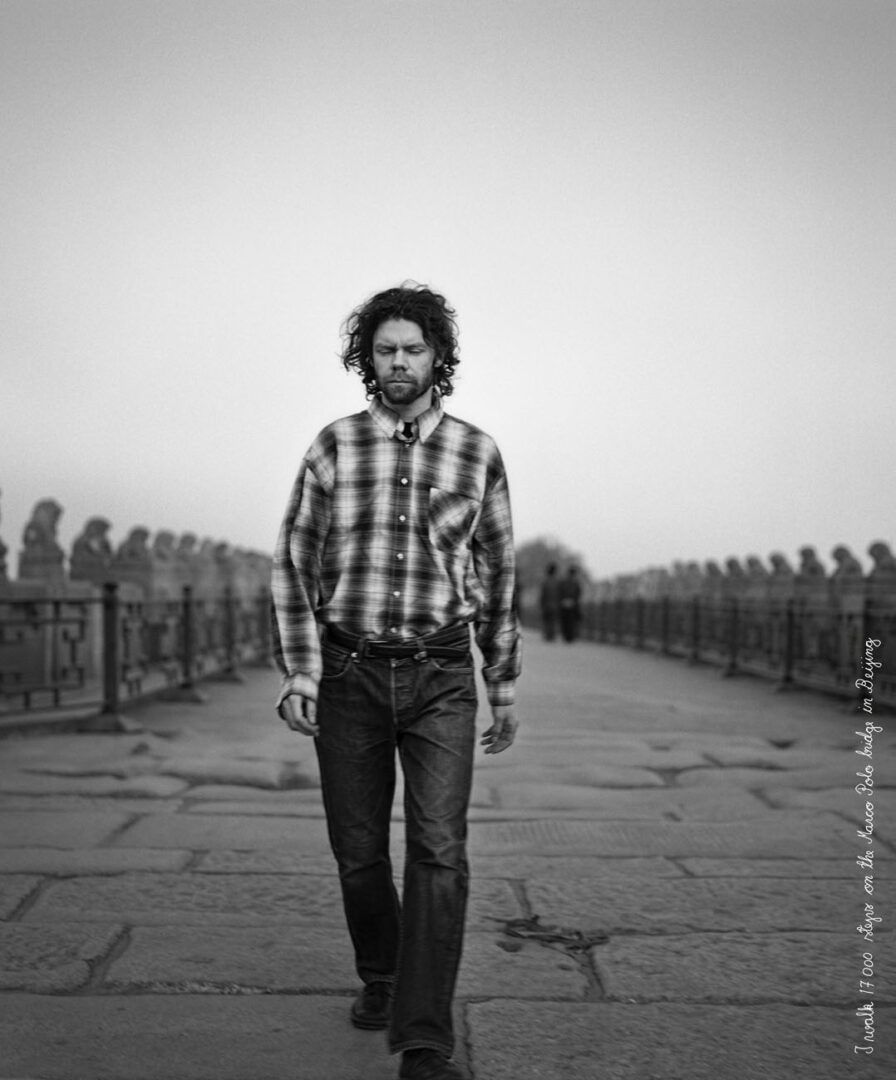

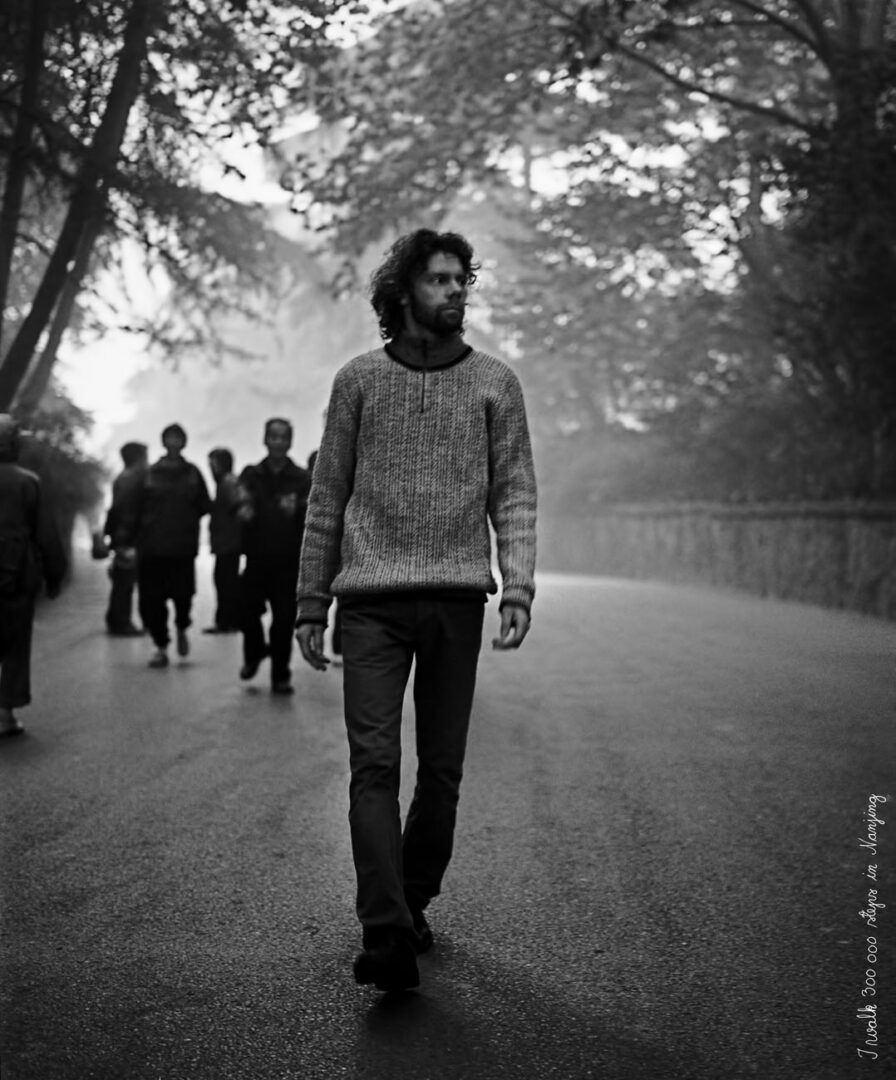

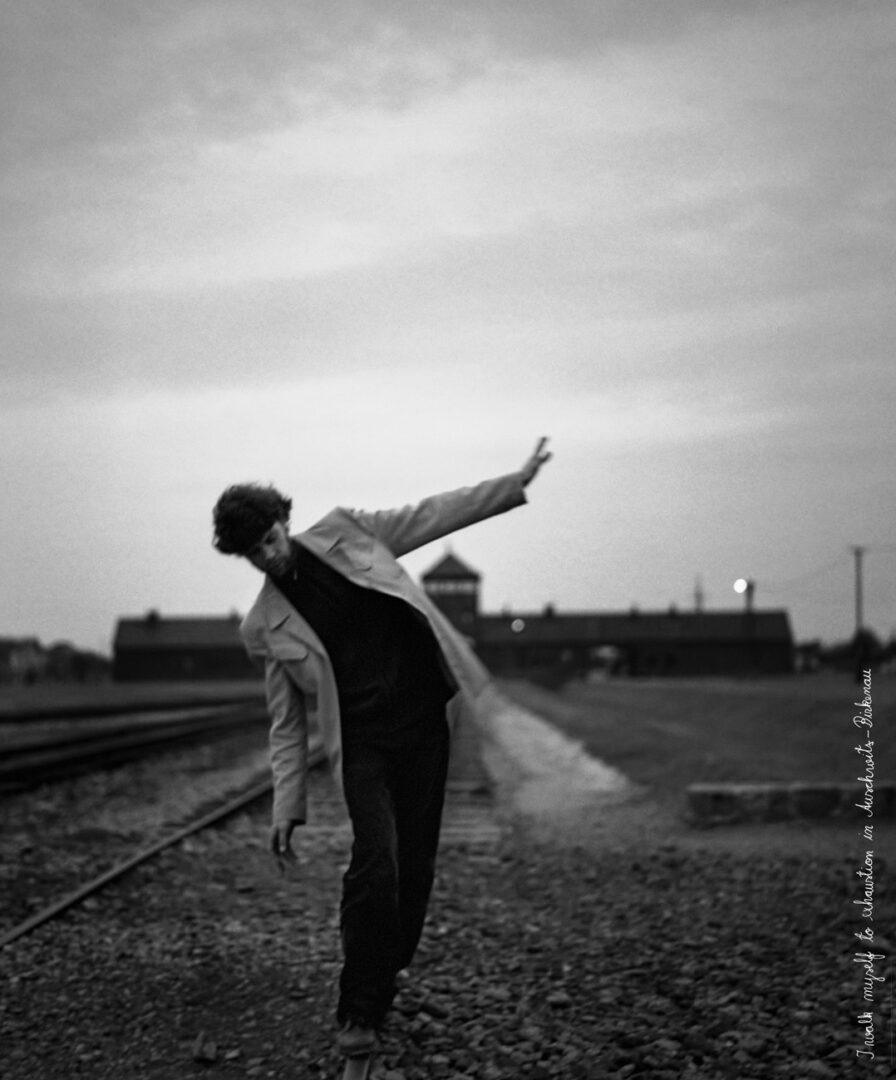

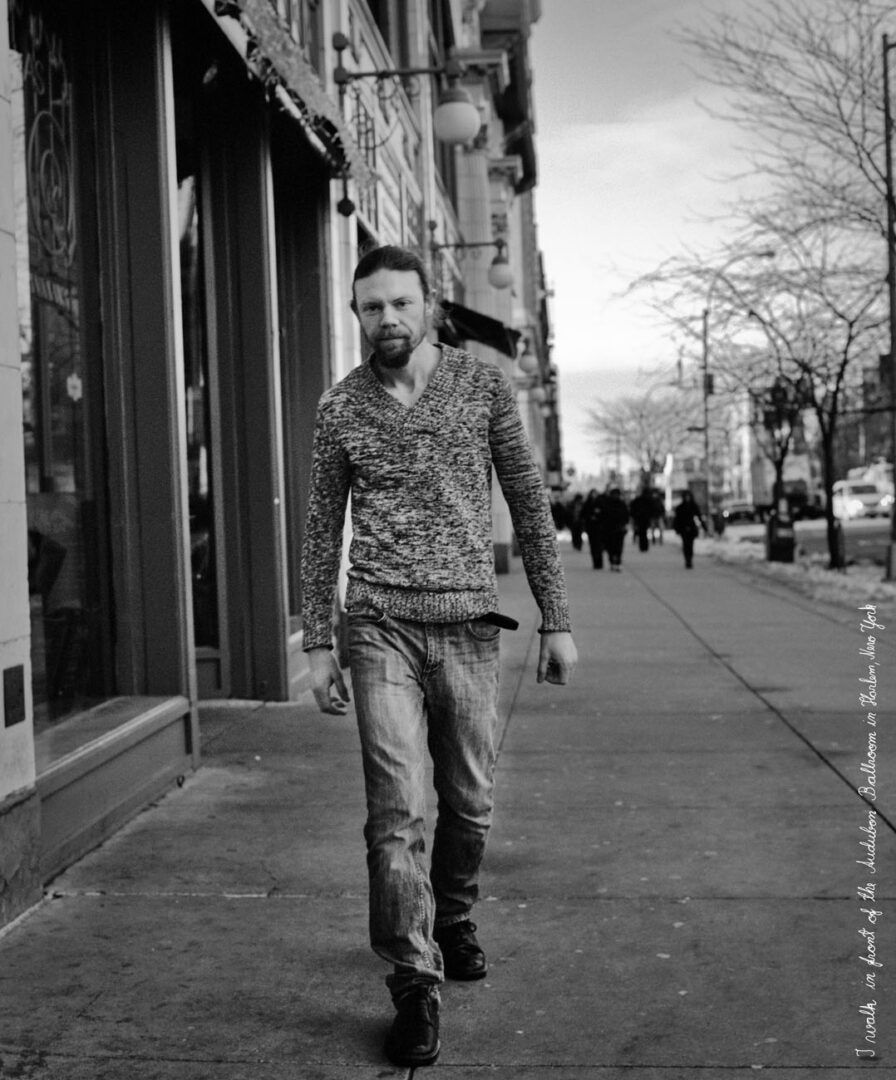

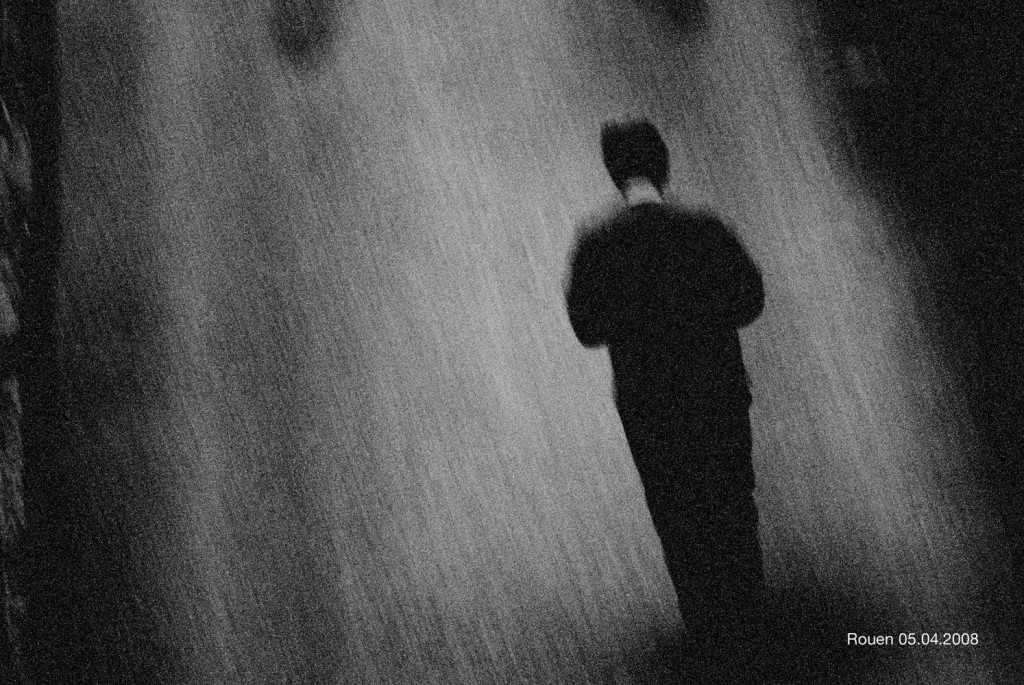

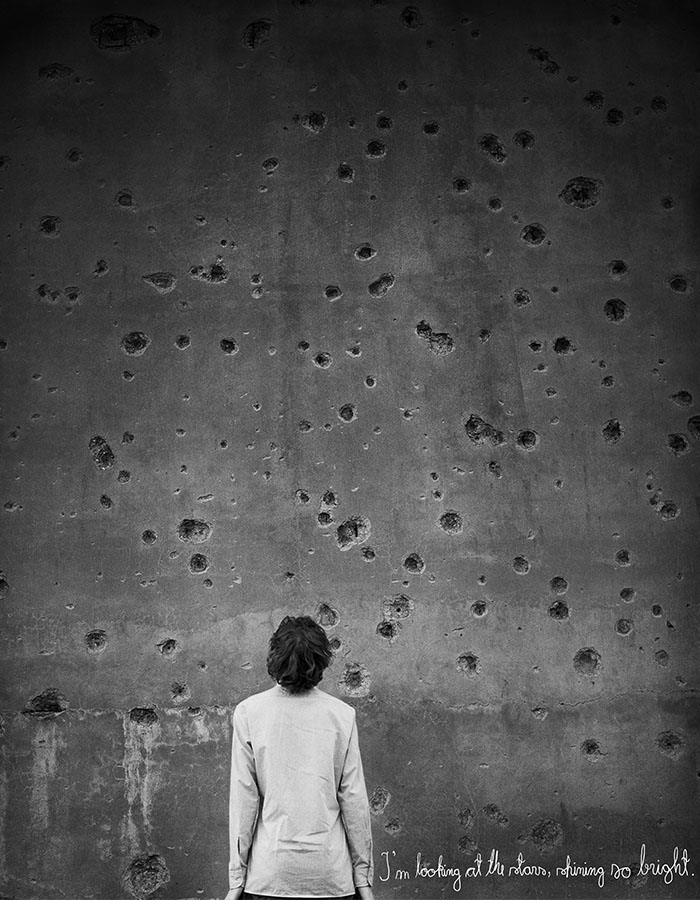

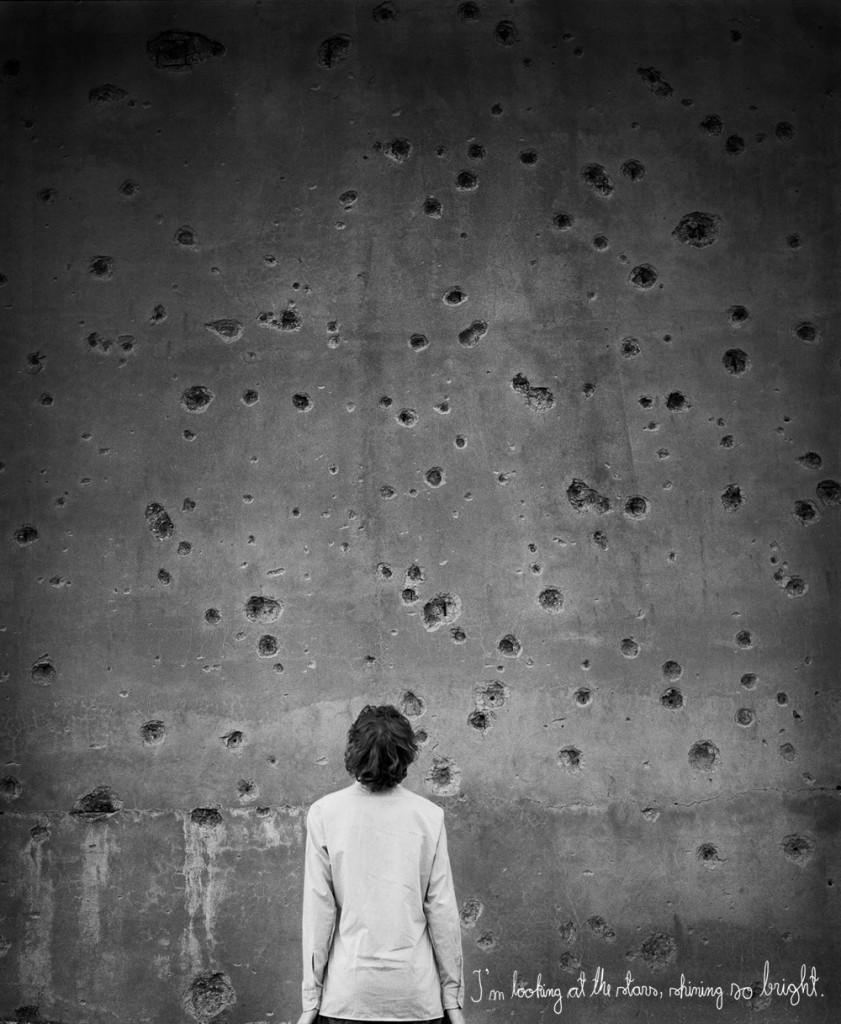

Many things have I witnessed through

this window. Faithfully it has reflected everything back:

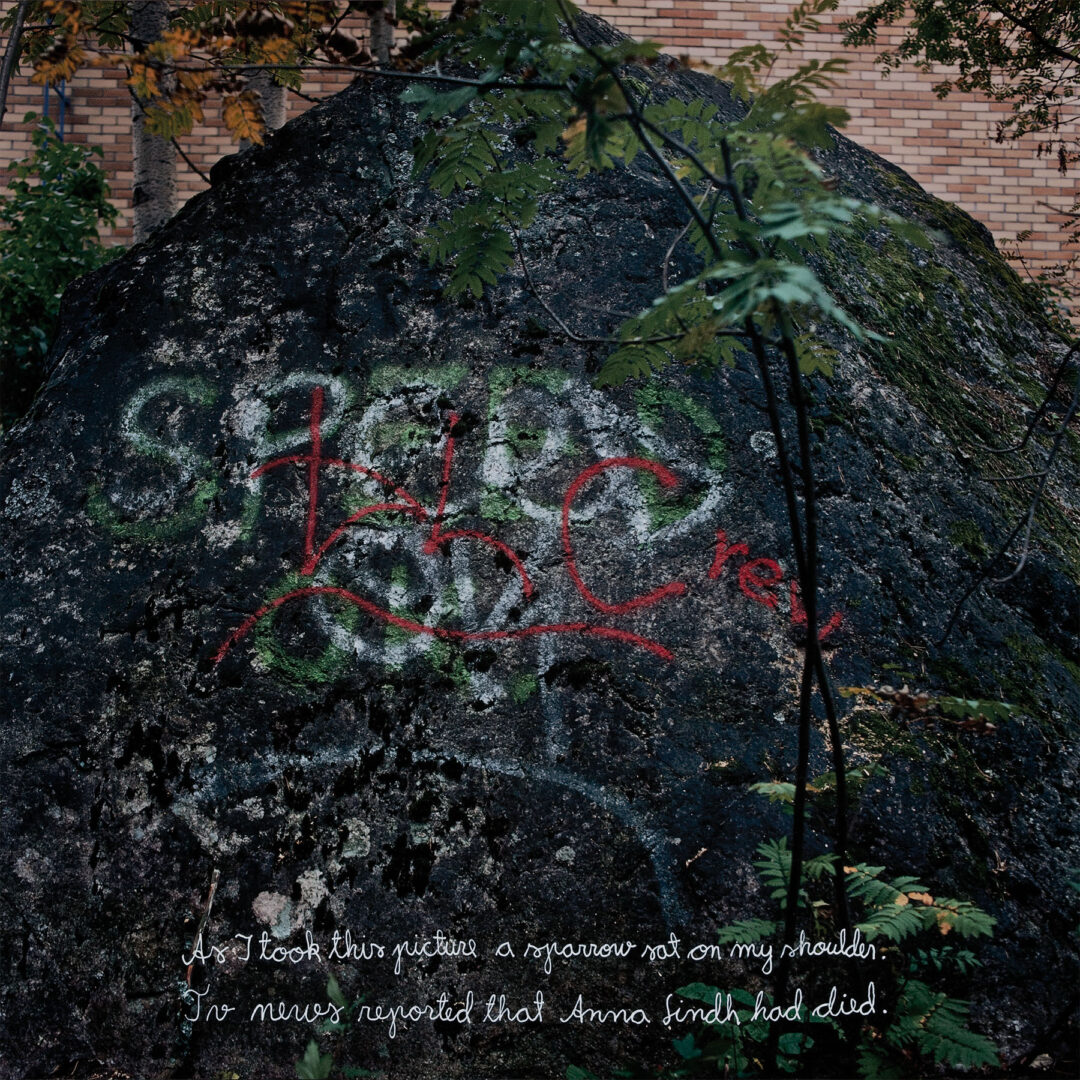

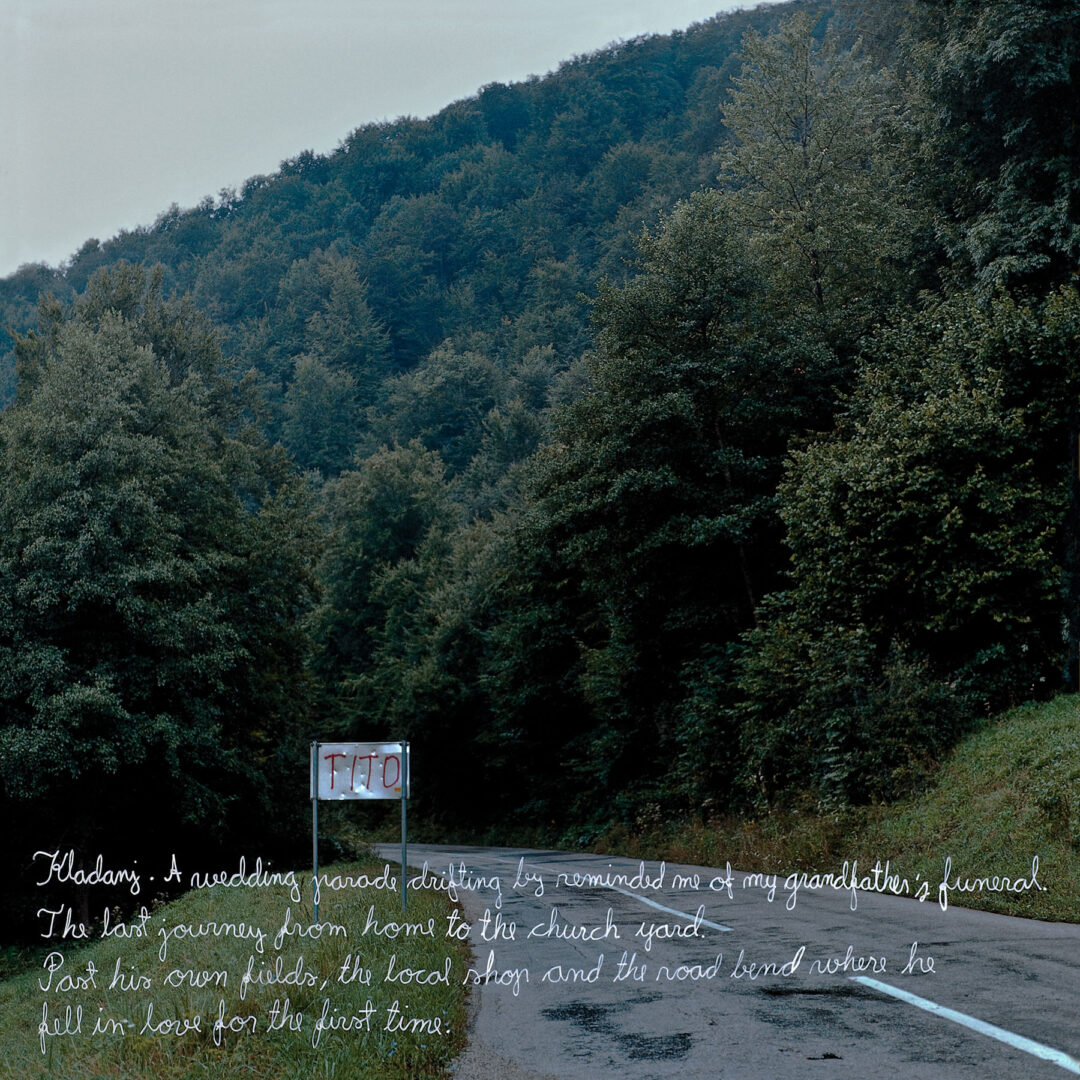

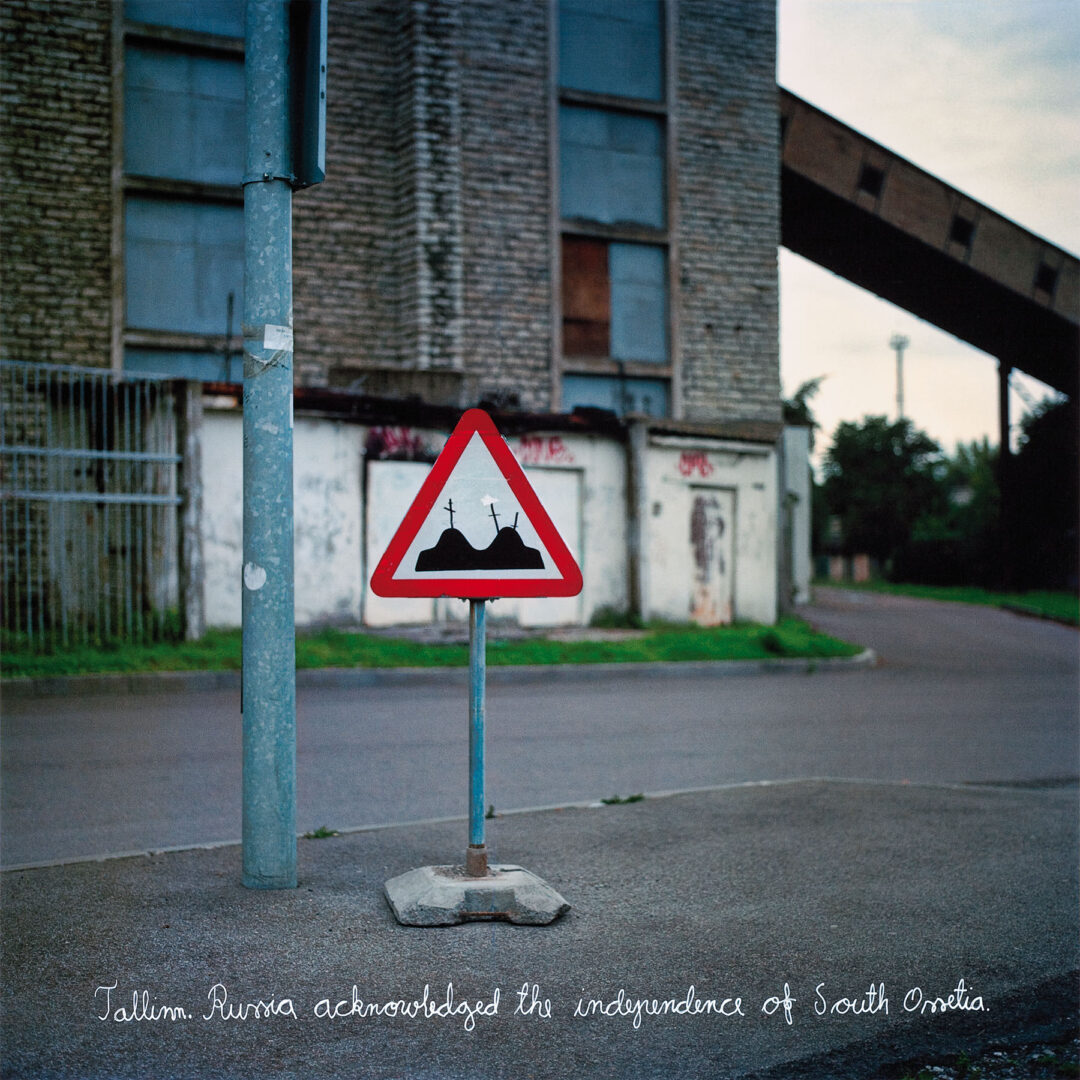

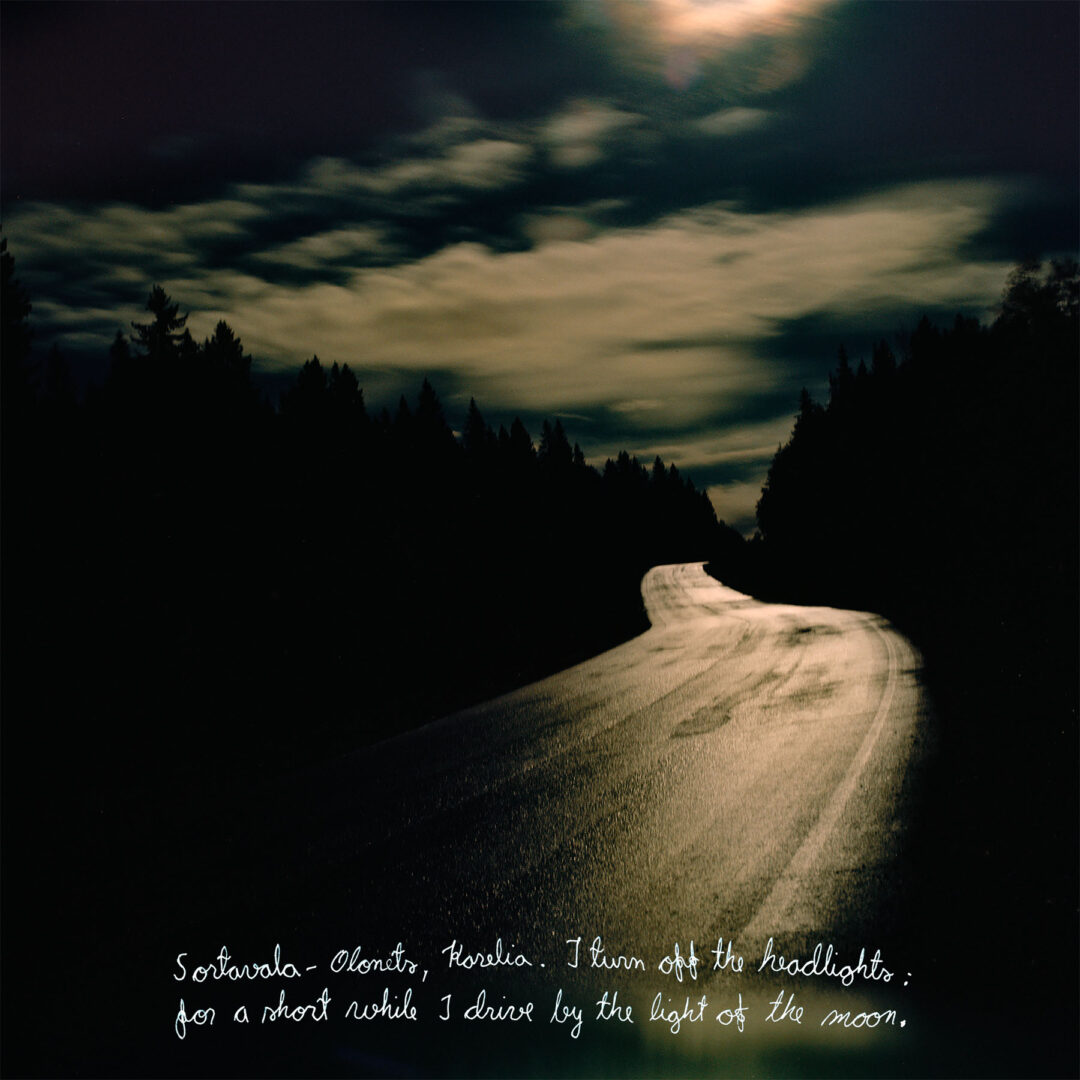

the road sign, fallen along the roadside,

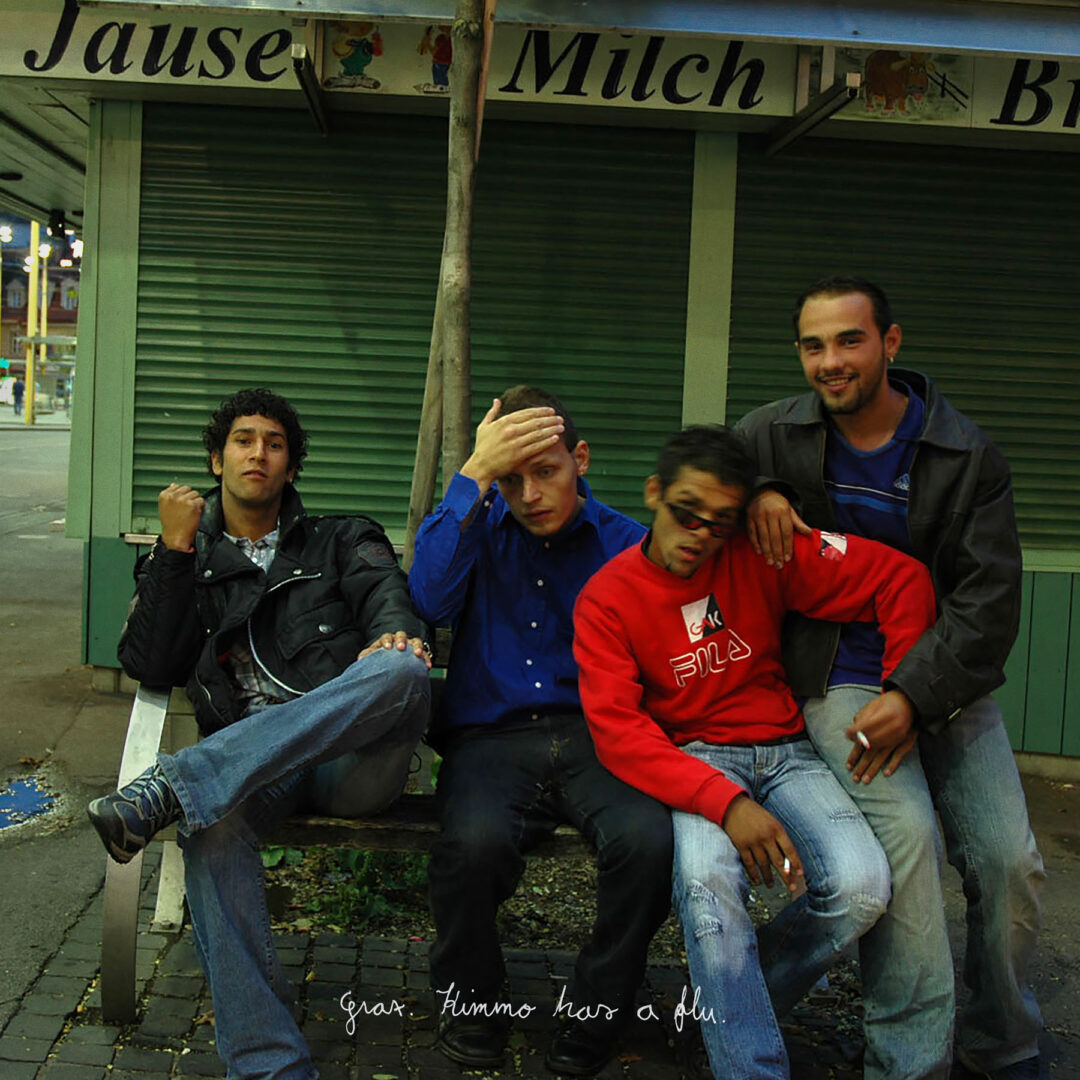

looks of the road users,

an invader’s march, the nails struck

though palms,

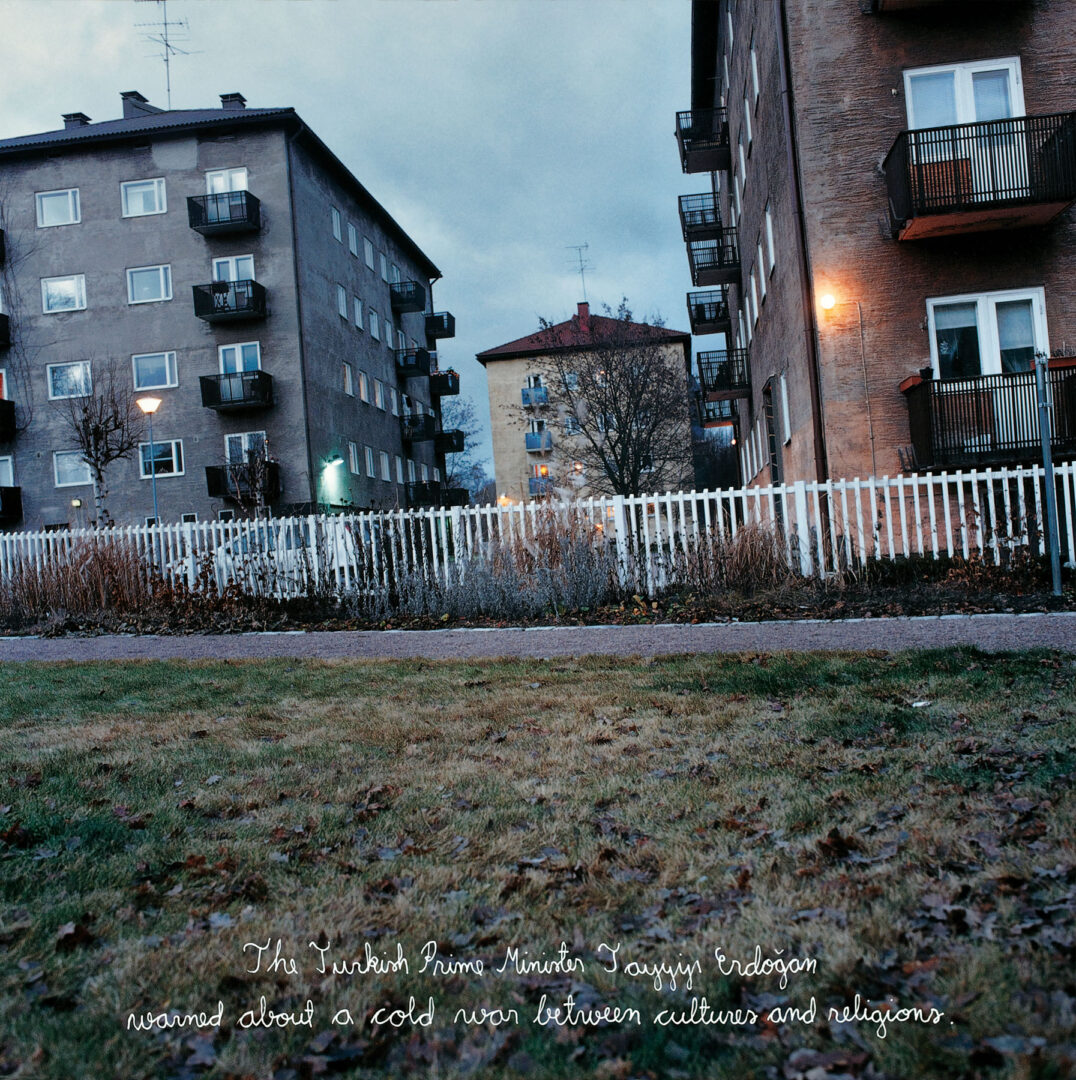

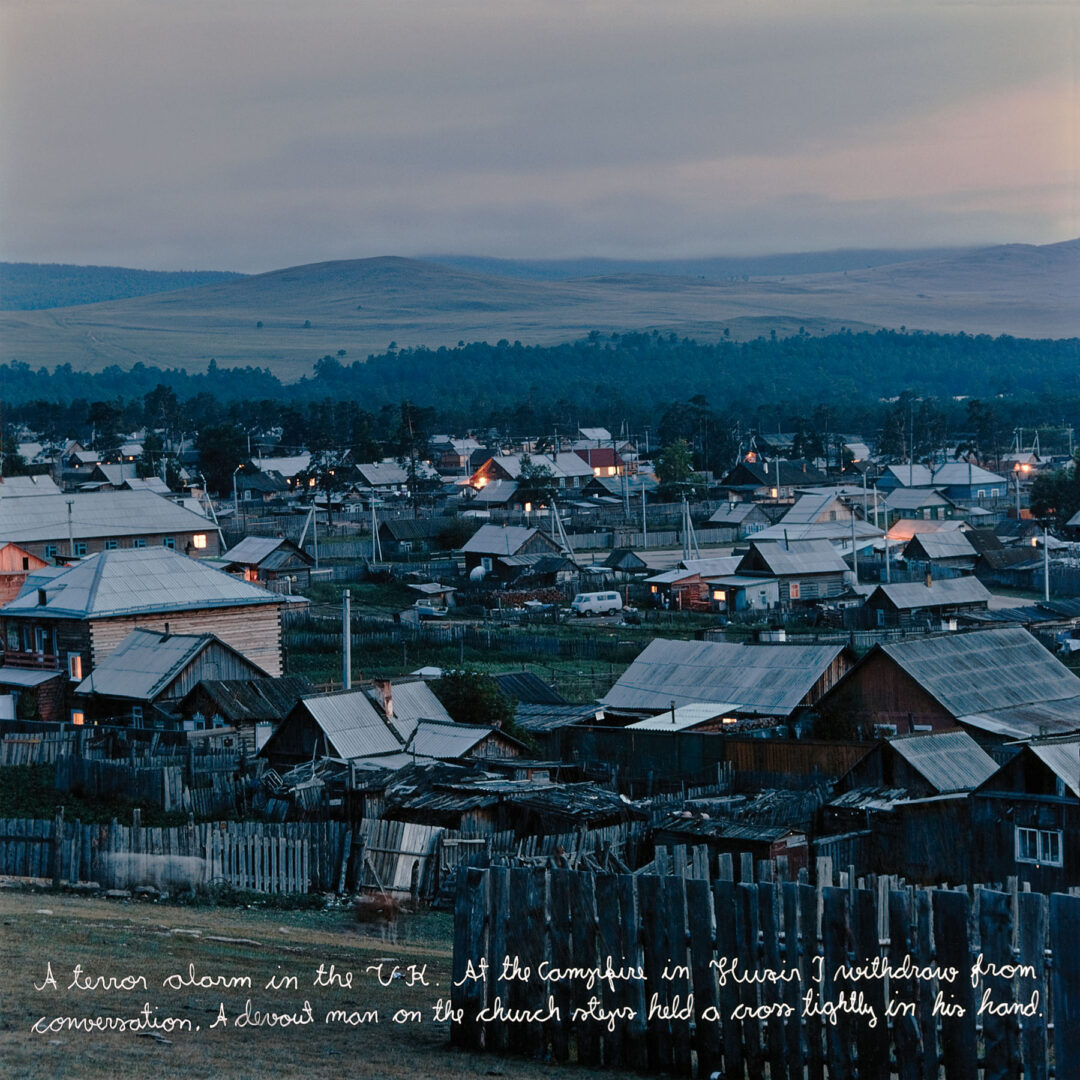

the noble family, the cold war, a singing

boy, banking crisis, yearning eyes,

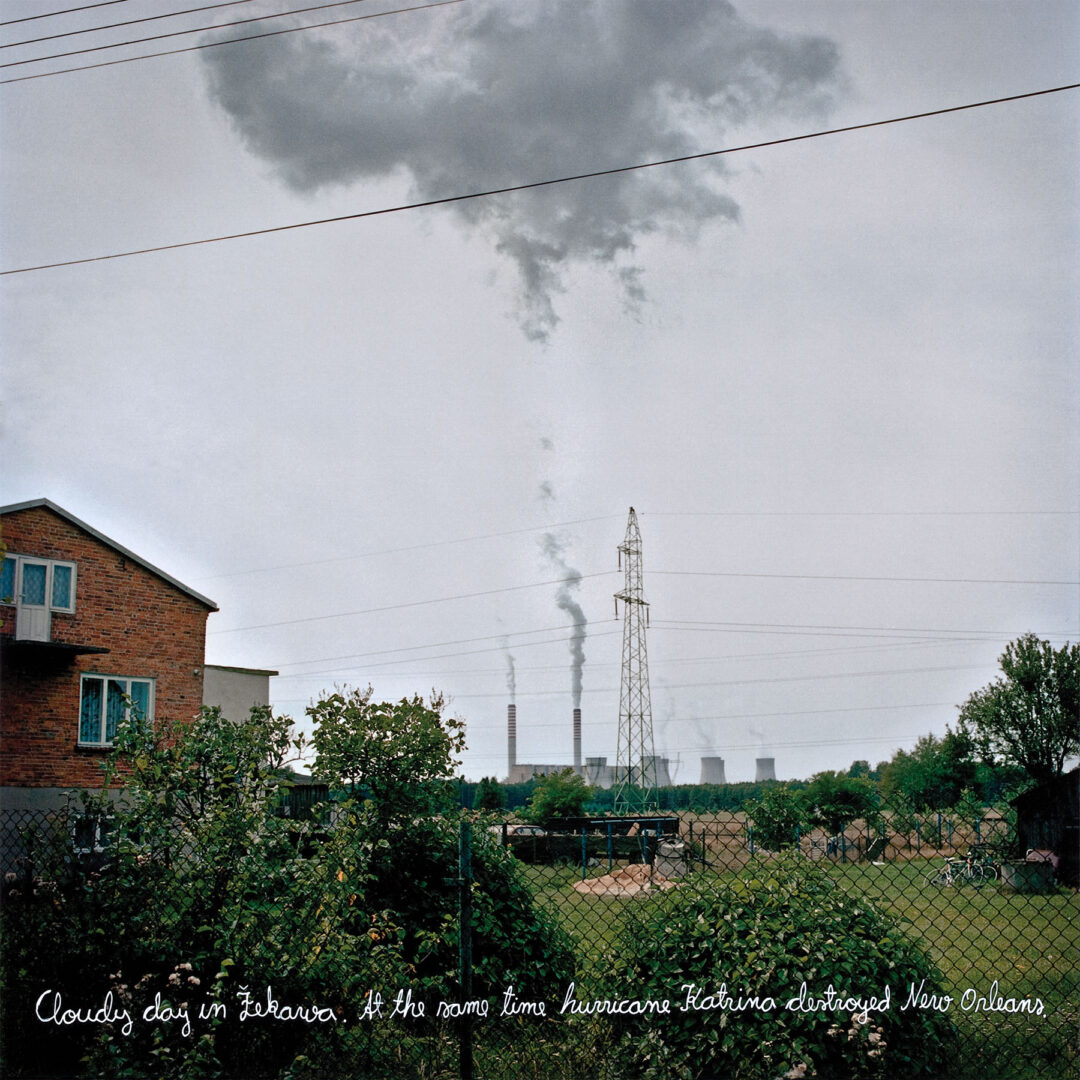

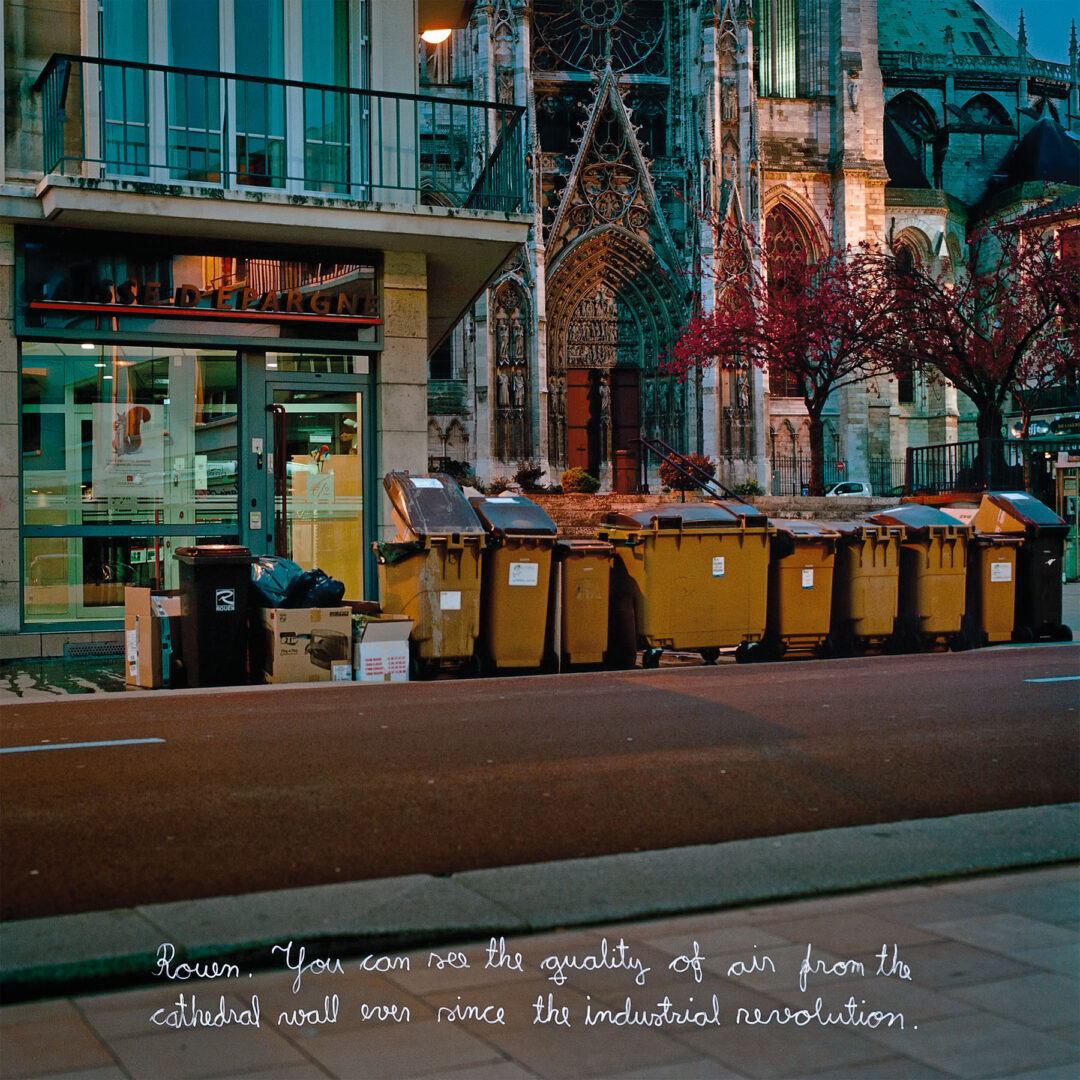

acid rain, the intoxicating flesh,

the dense silence, cries of pain,

aimless rushing about, an injured knee,

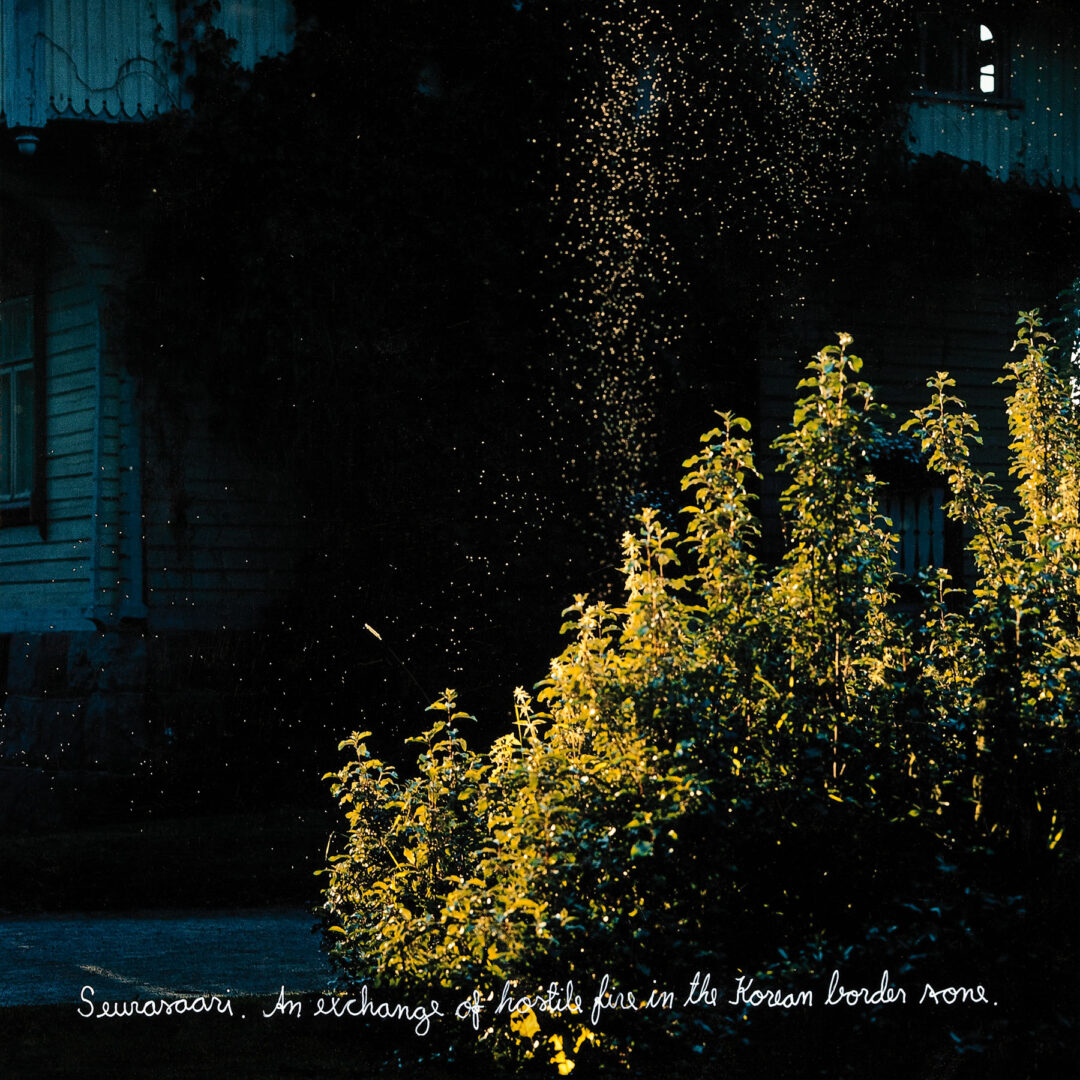

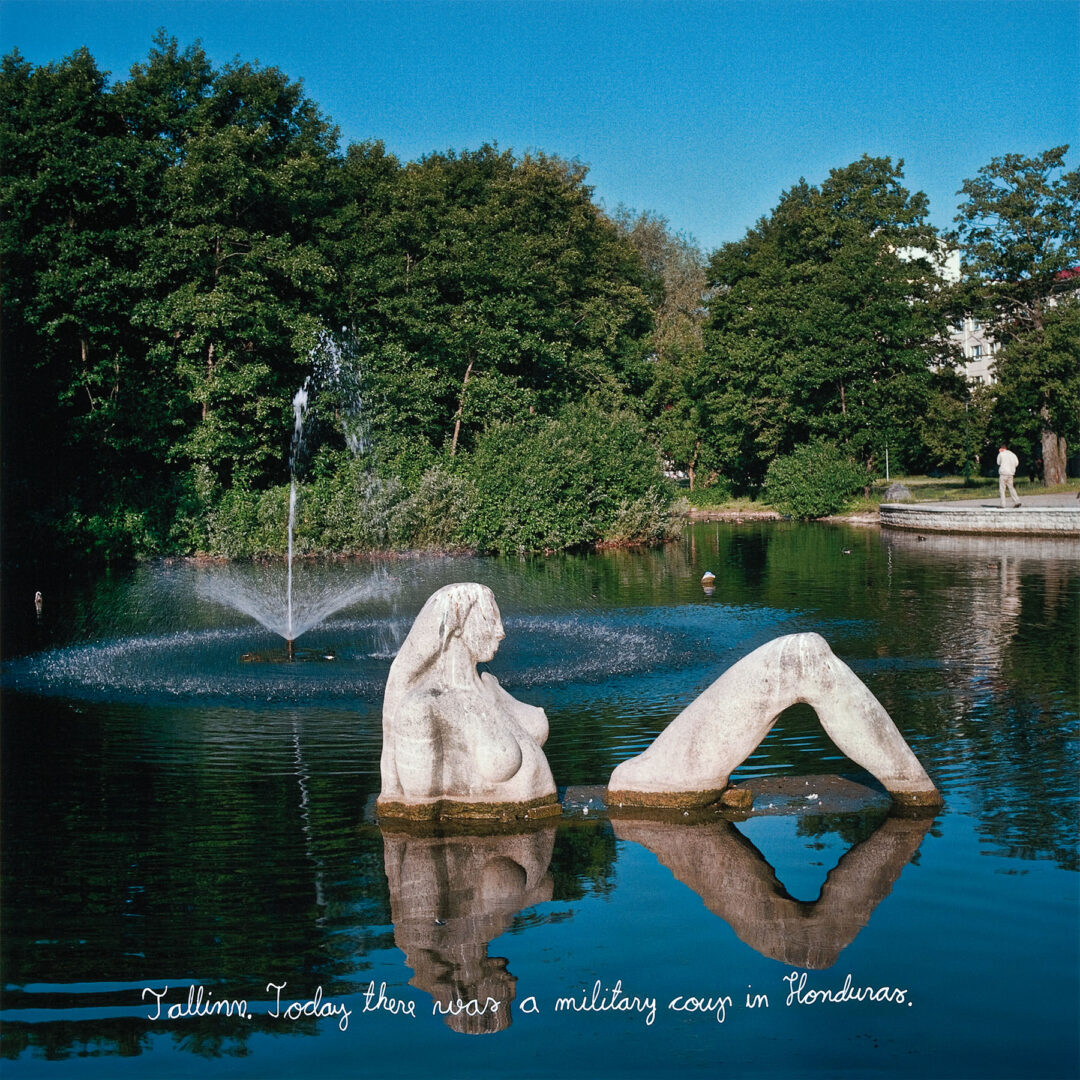

monuments, natural phenomena,

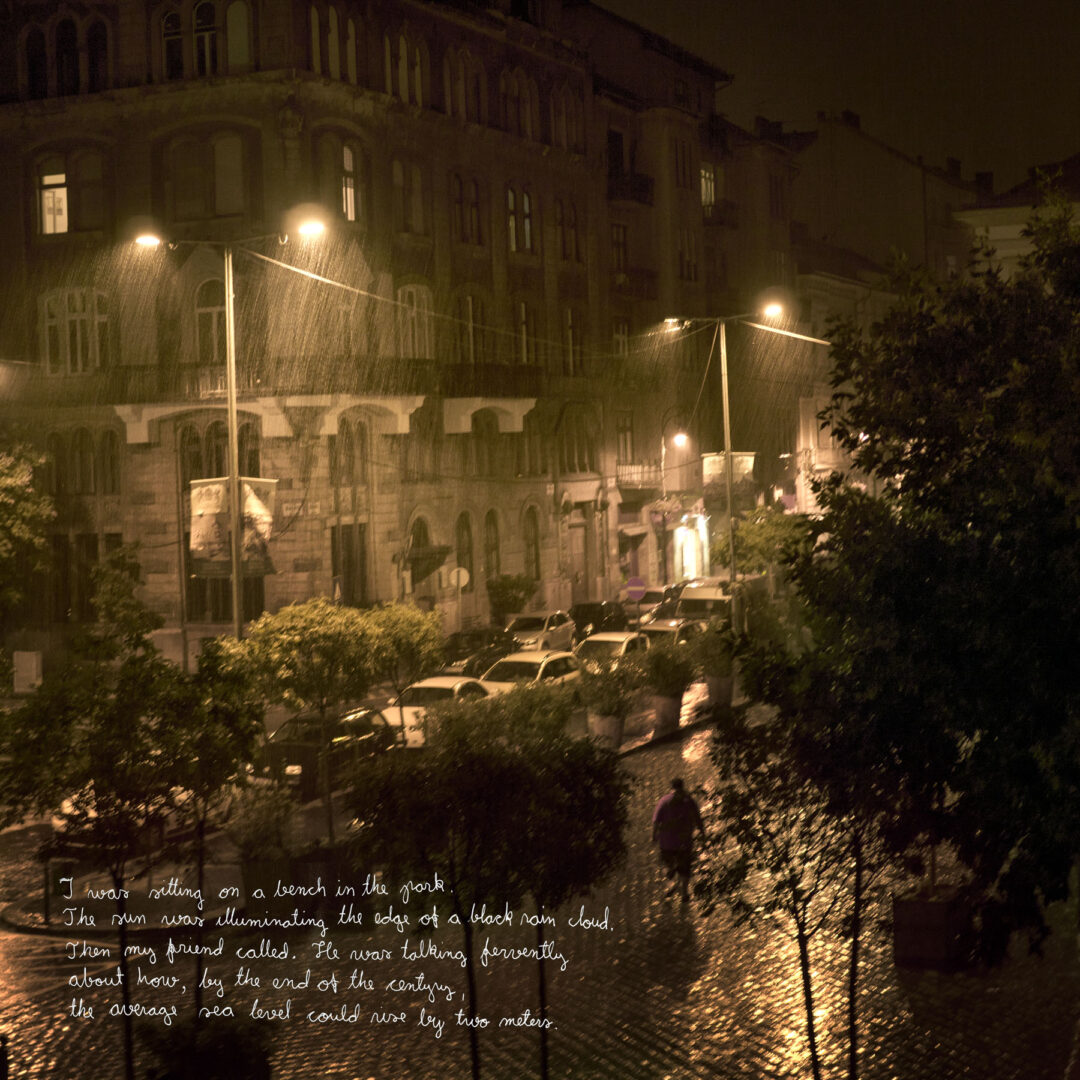

insecurities, the rising sea level,

stovepipes forever dead now, retaliation on generation

after generation, uninvited guests,

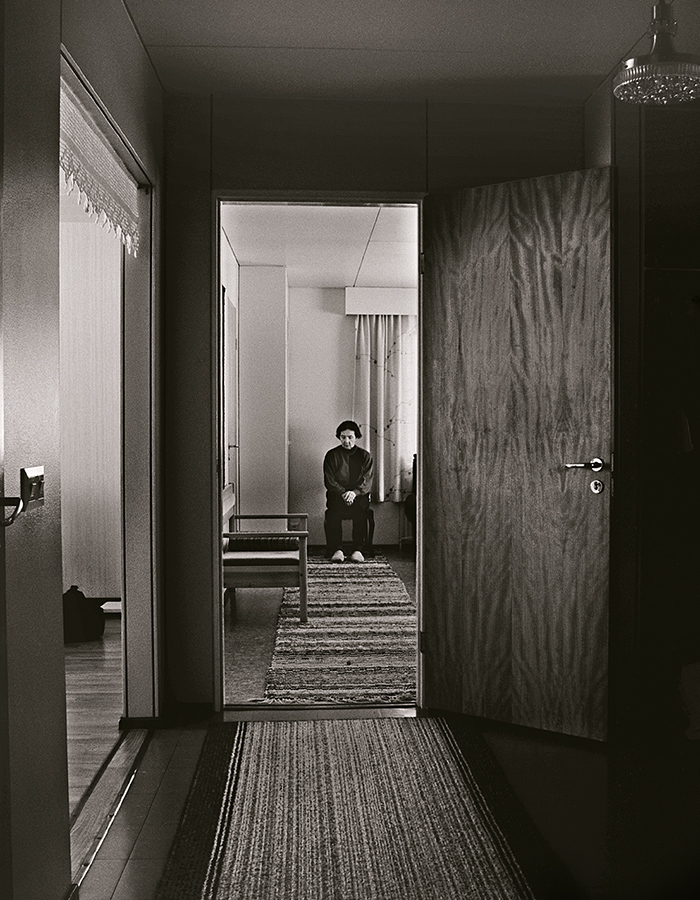

the cellar door,

the missile crisis in Cuba,

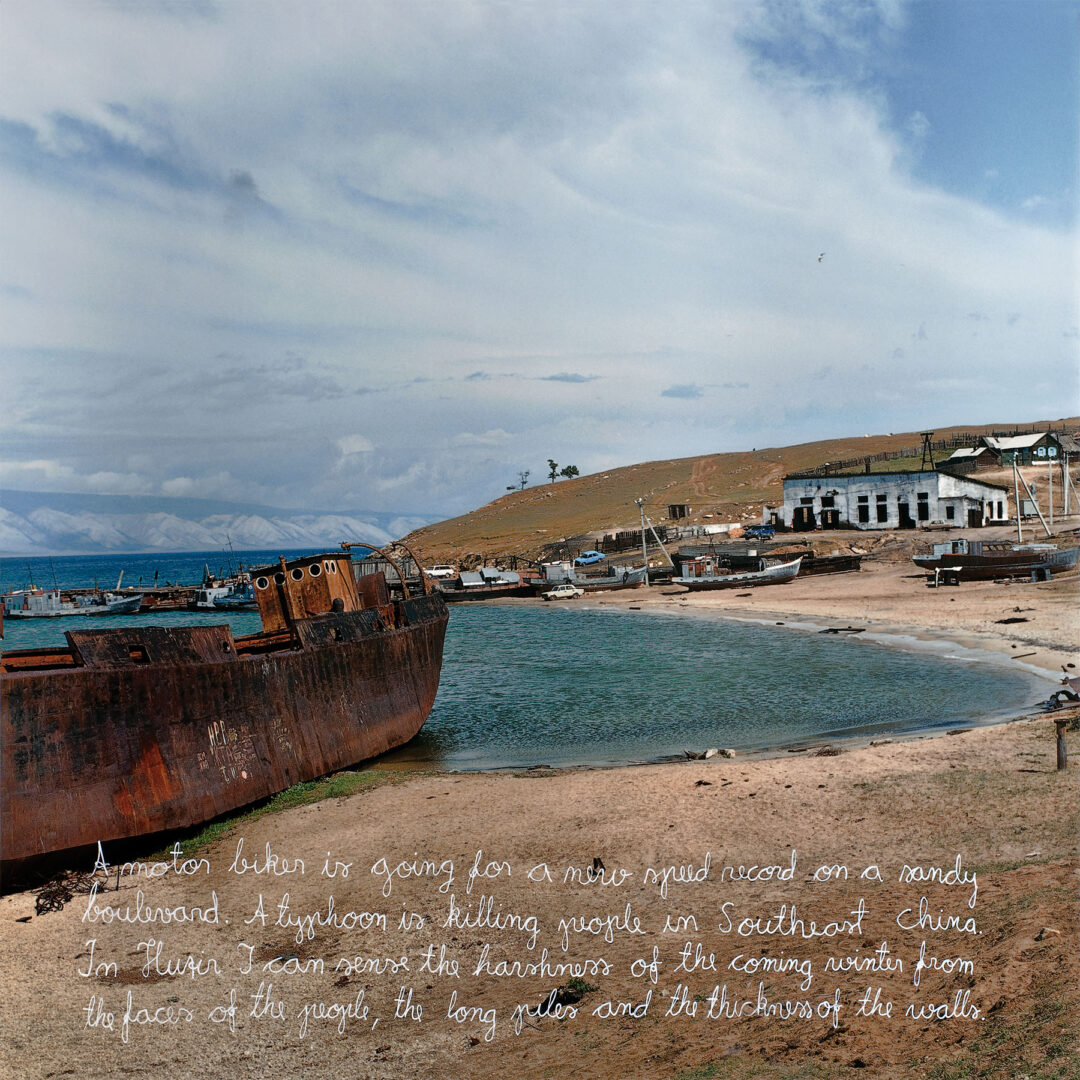

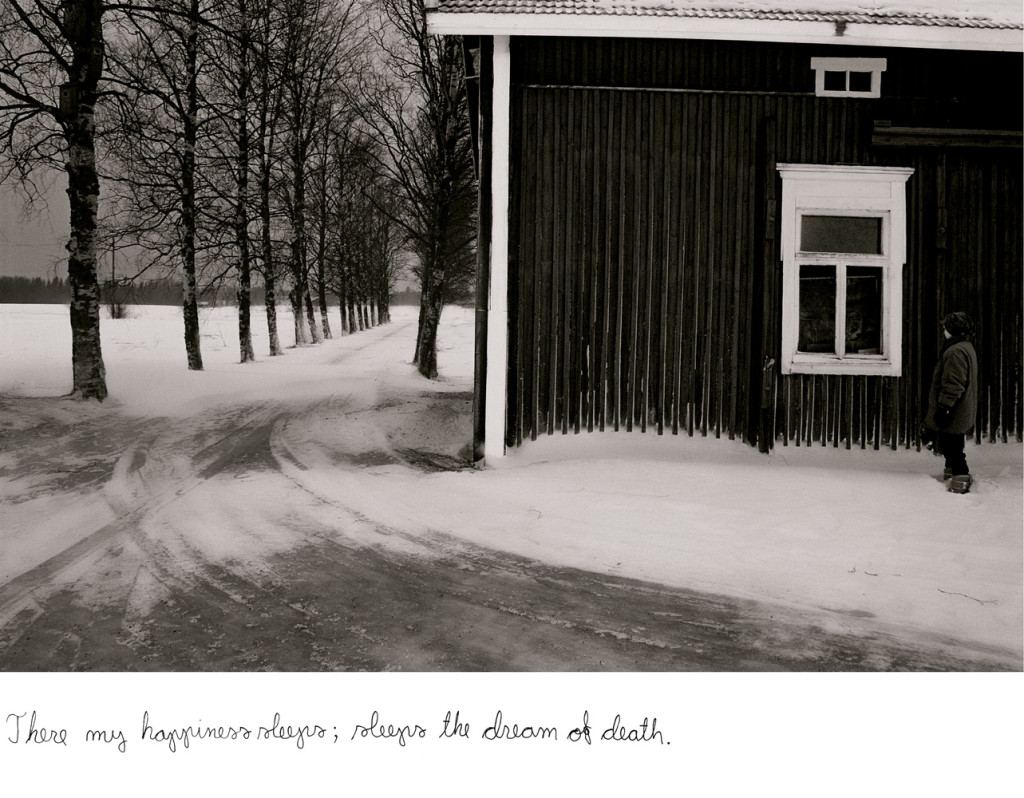

travels long as light years, the birch-lined alleyway,

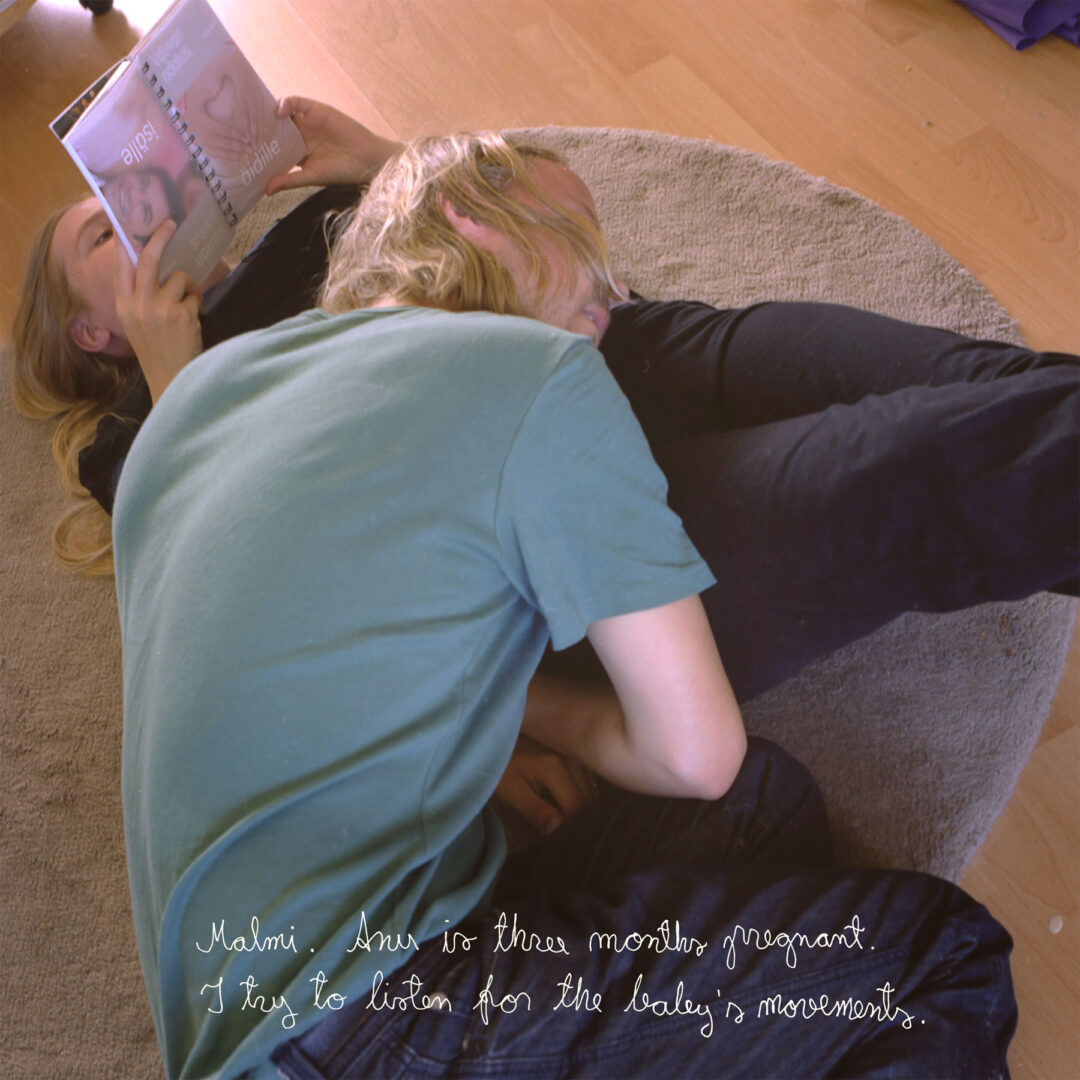

the unstable cradle, the low altar.

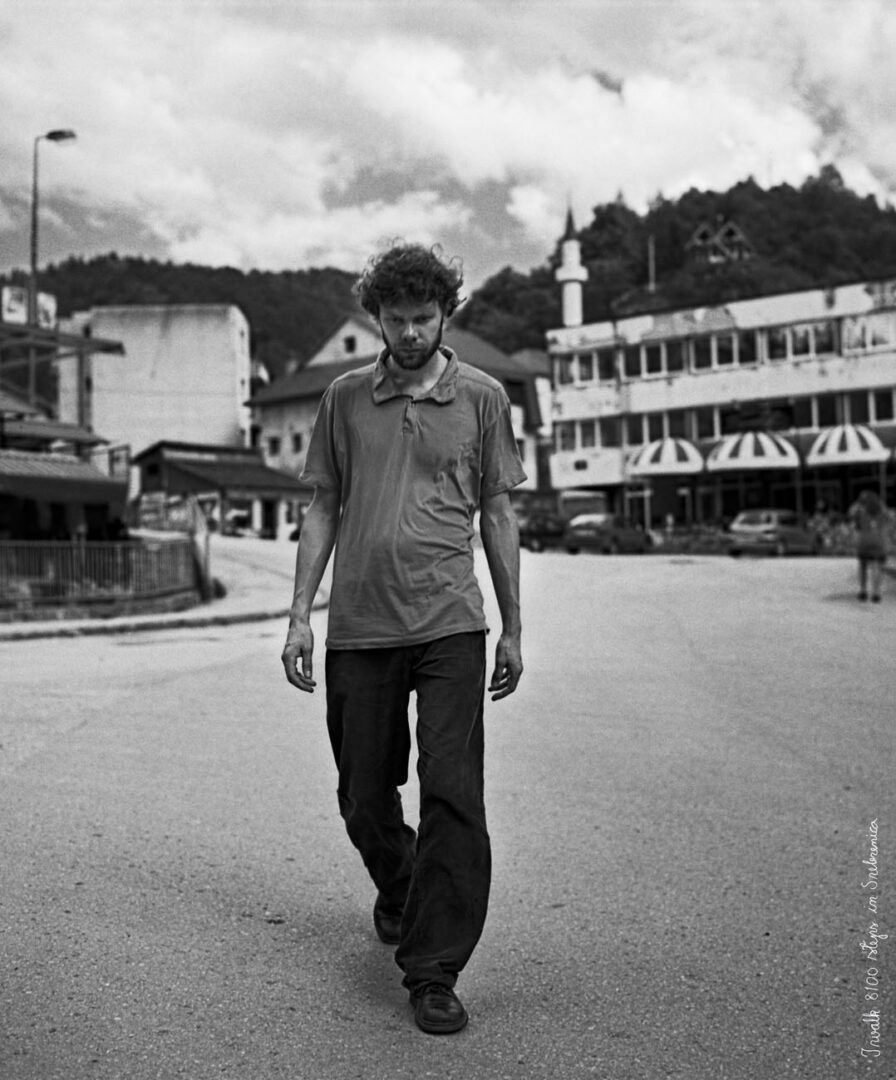

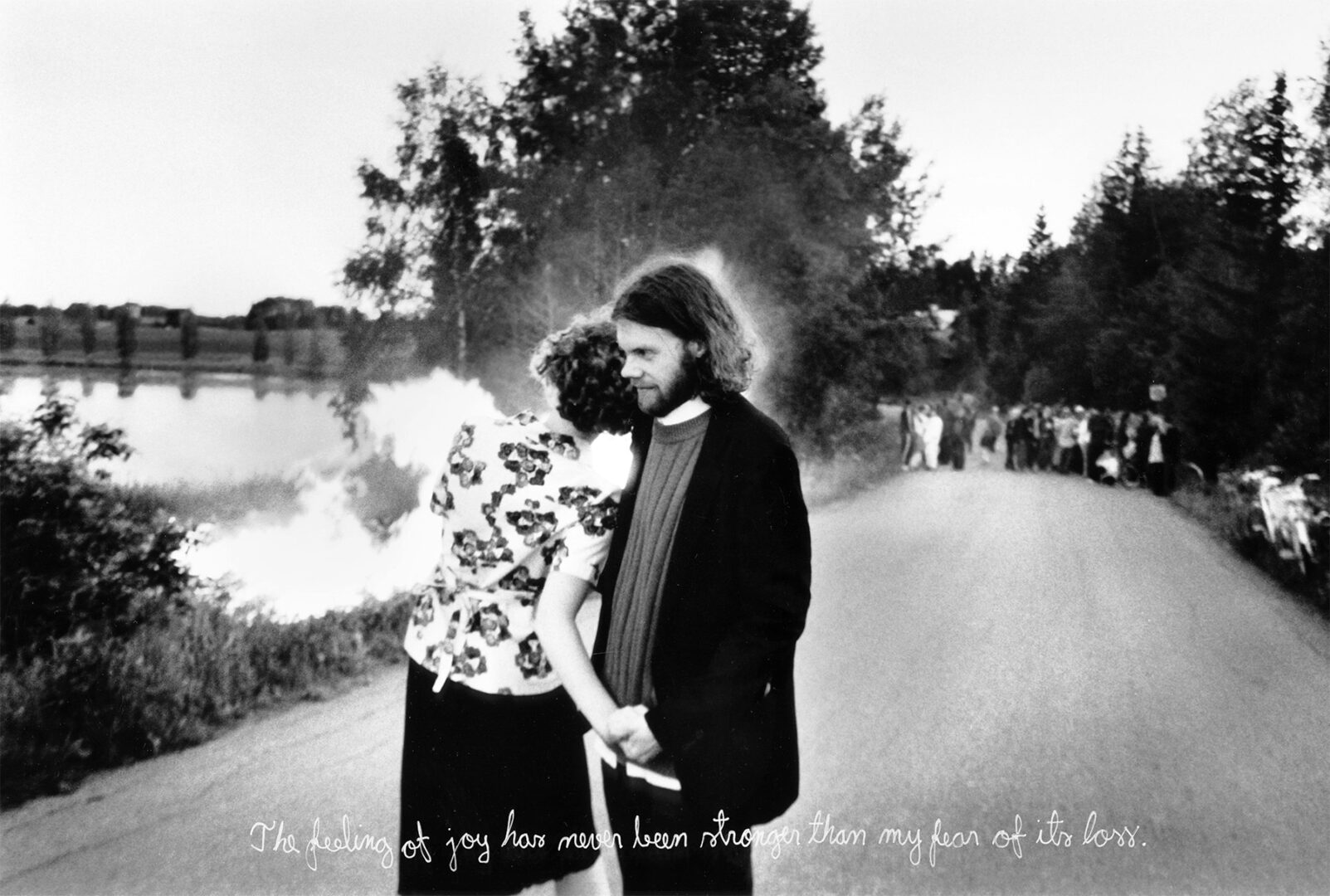

the wooden boats burned in Midsummer bonfires,

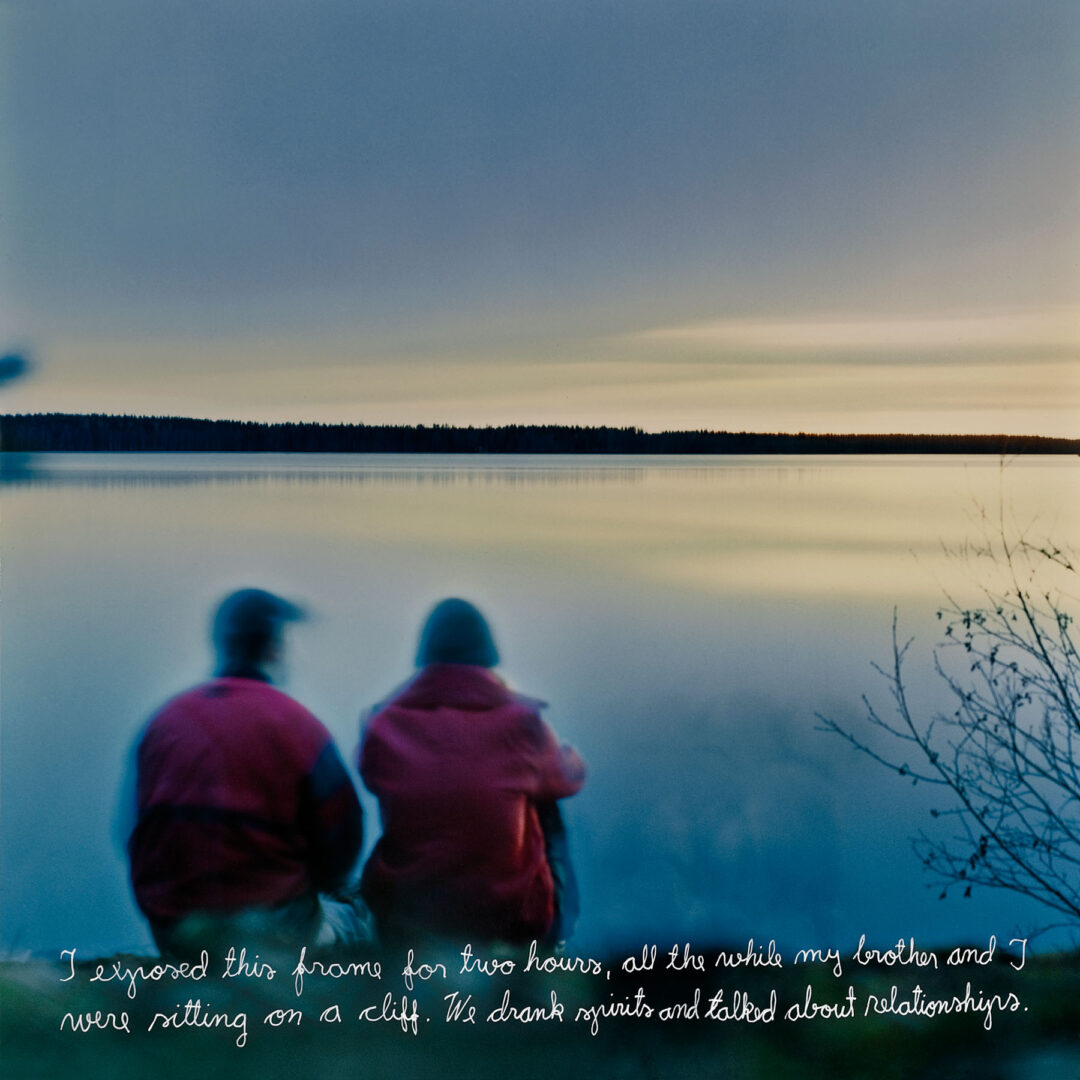

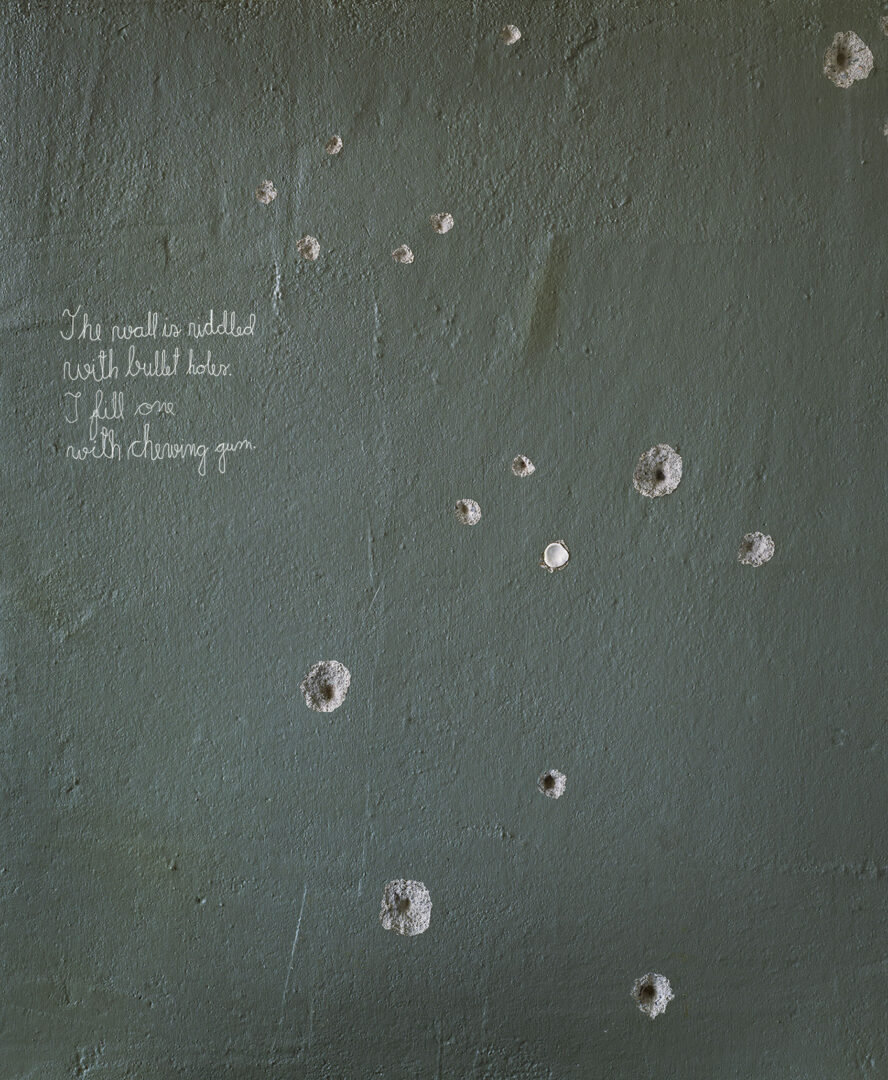

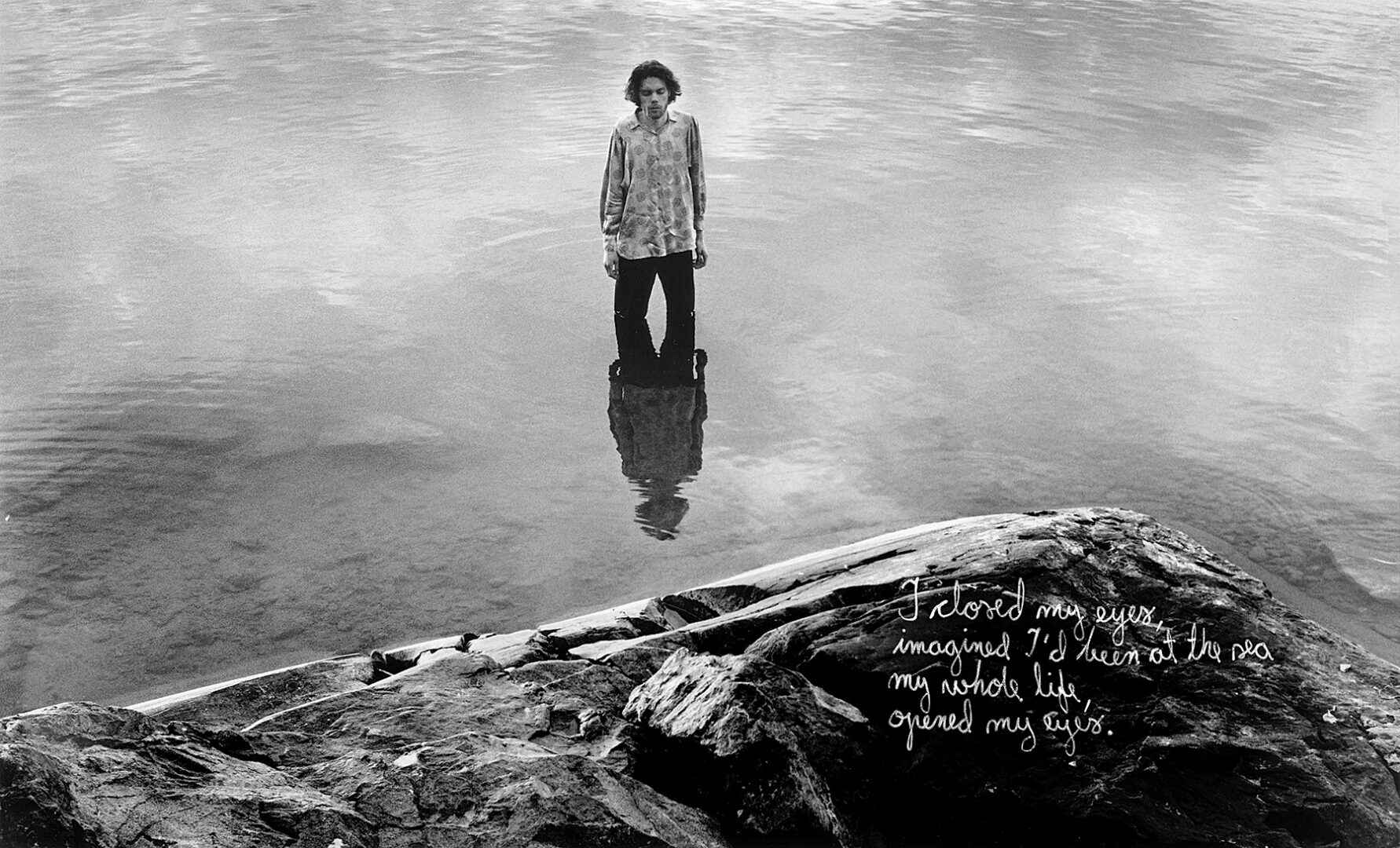

rebuilding, the stones skipped on water,

the mute mouth of my gentle father

the swollen rowan berries

the drunken birds

hay poles and diesel engines

the pink dress, blooming willowherb

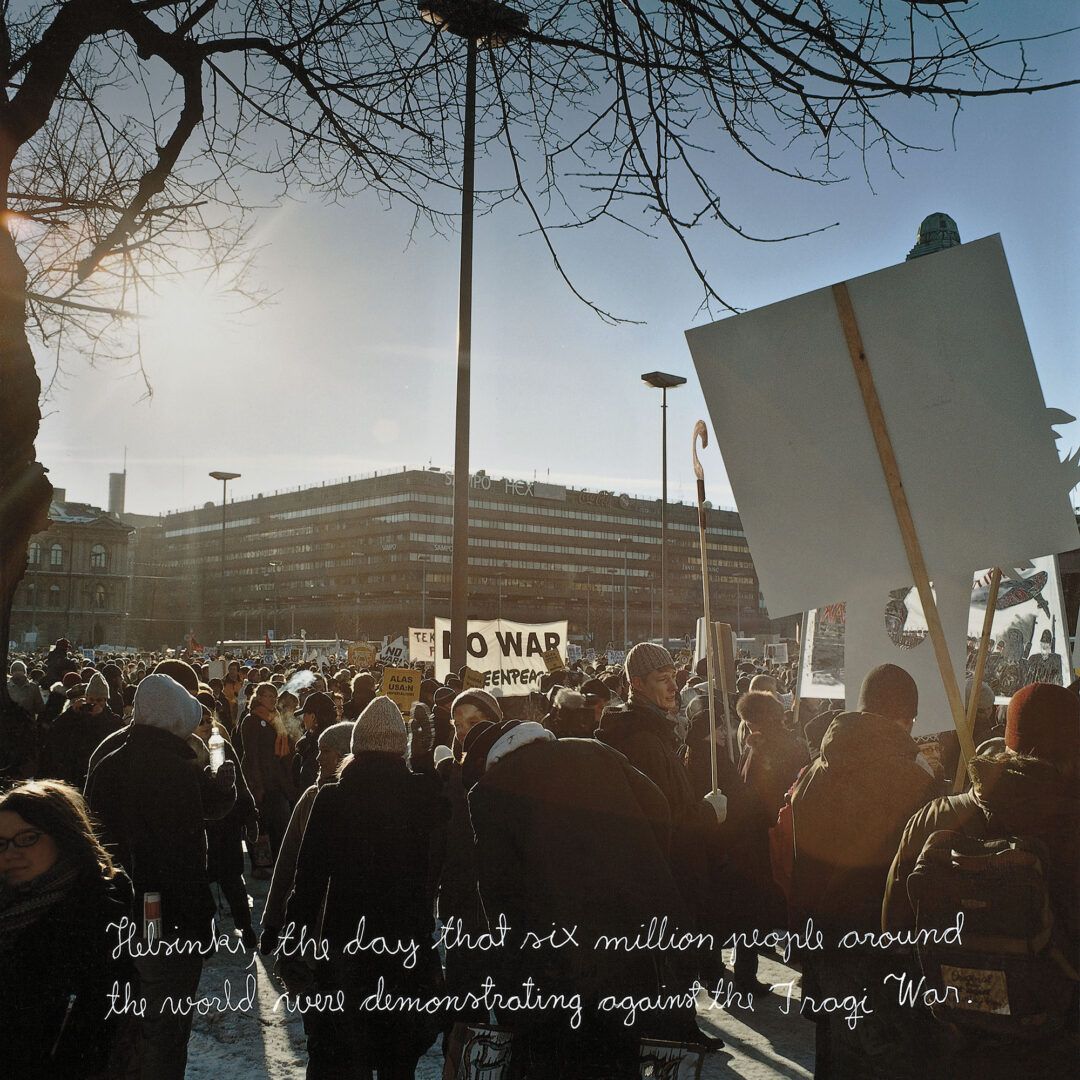

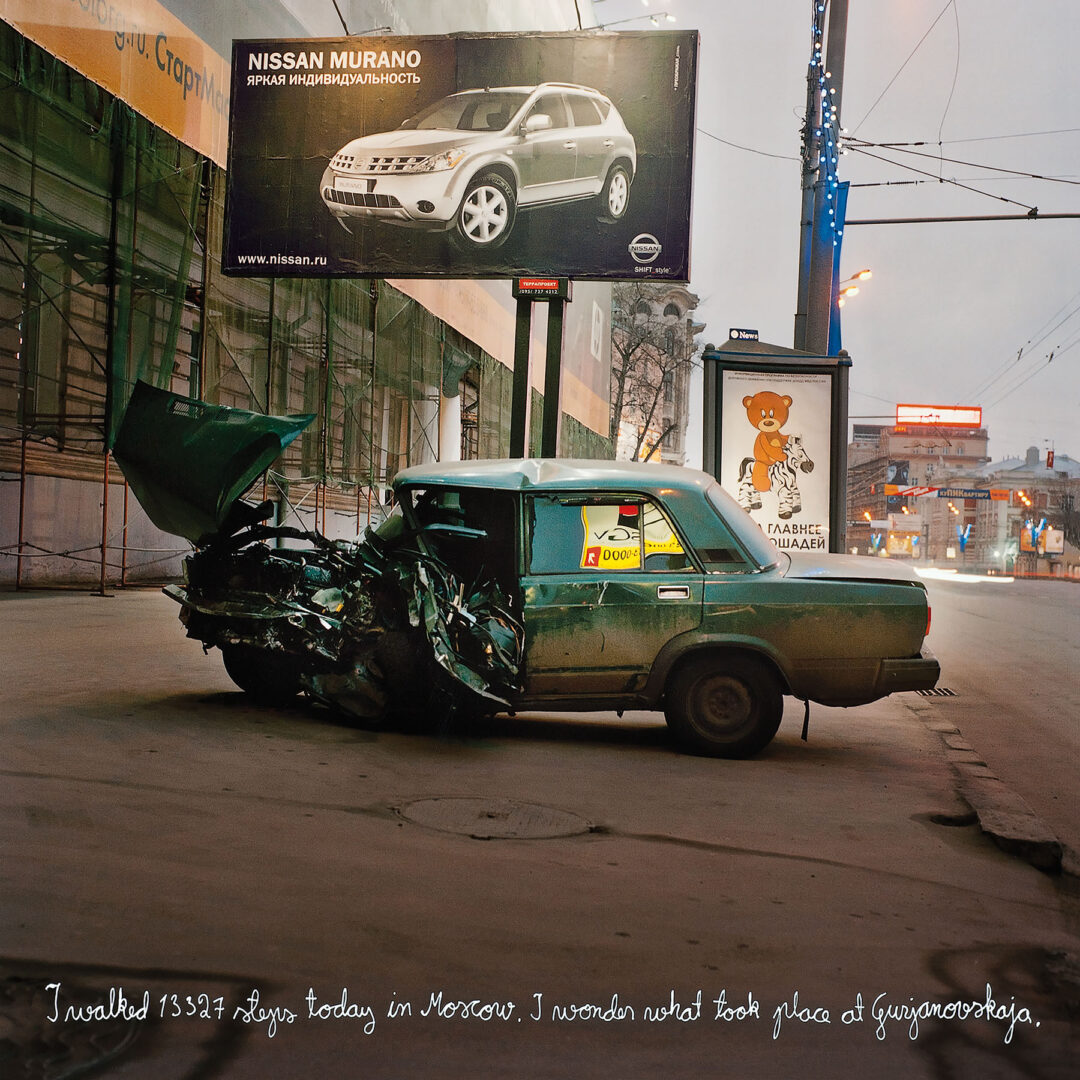

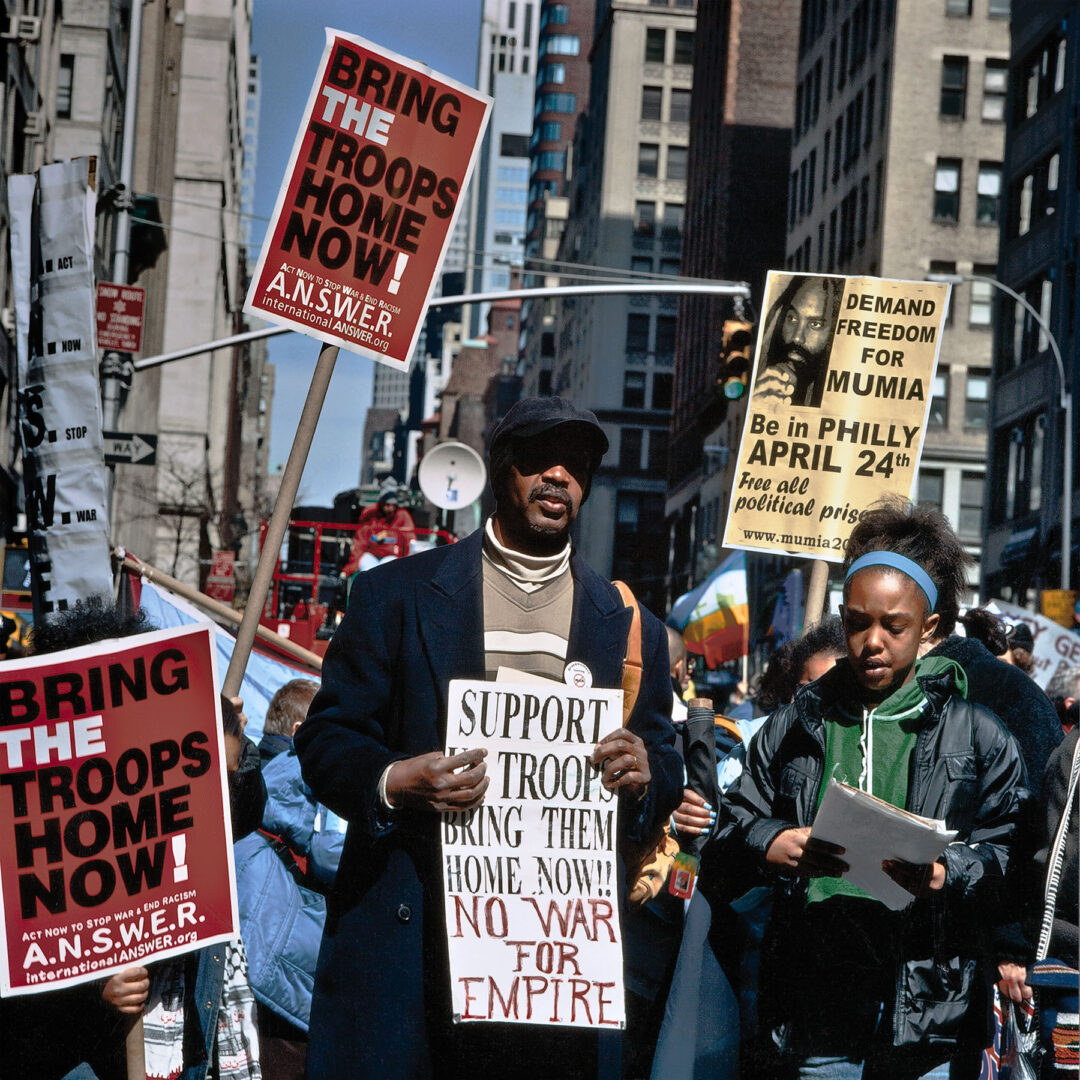

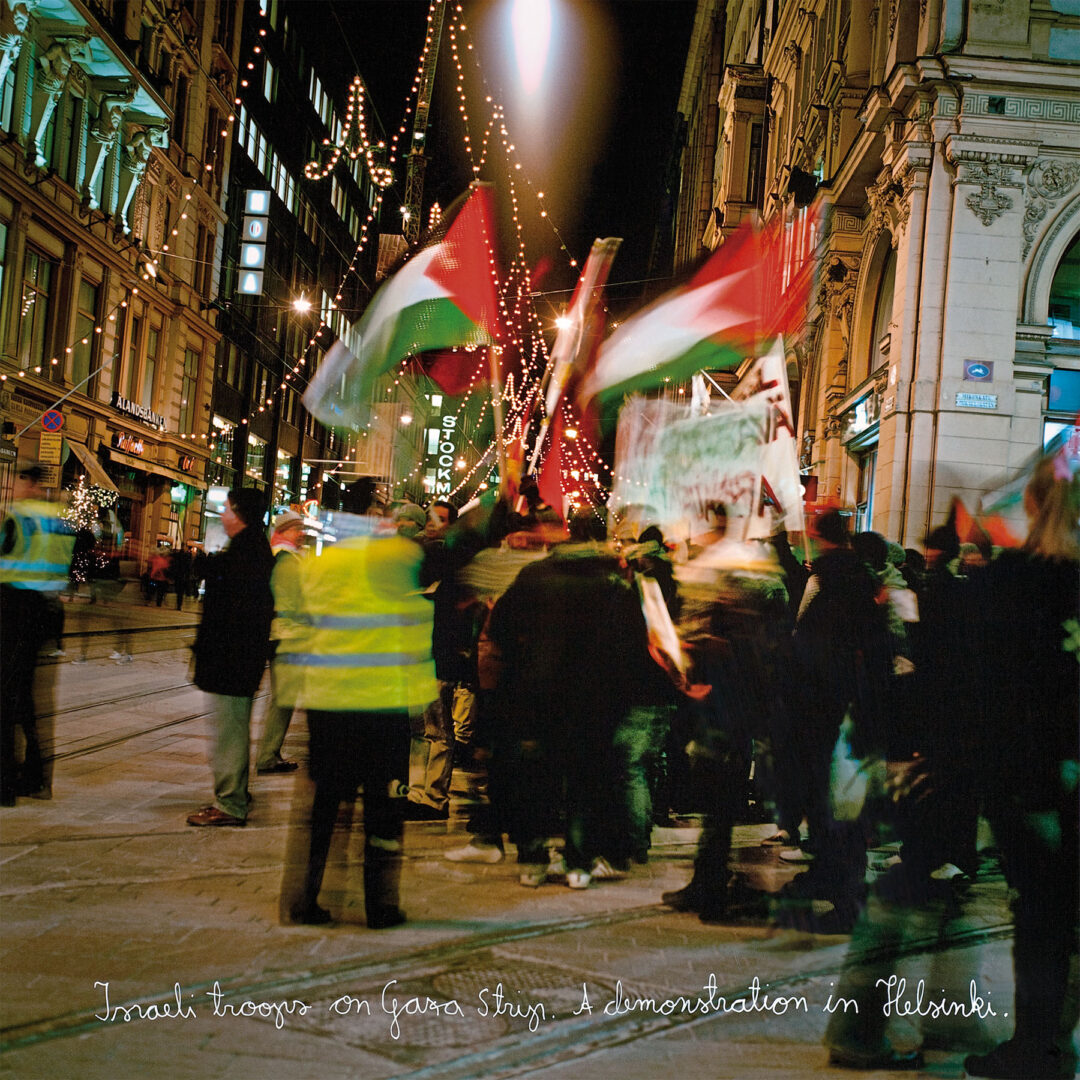

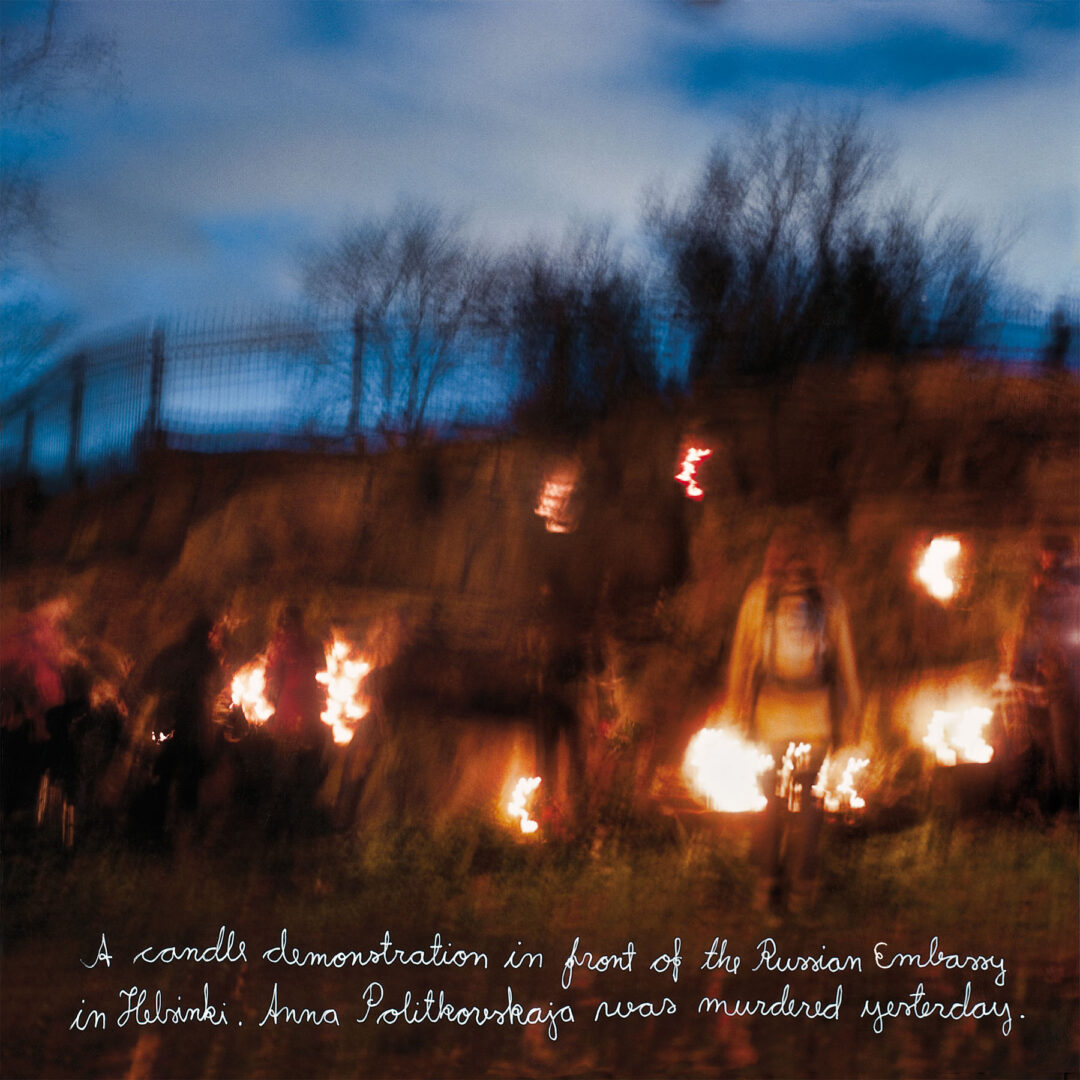

the demonstrations, noise, contempt

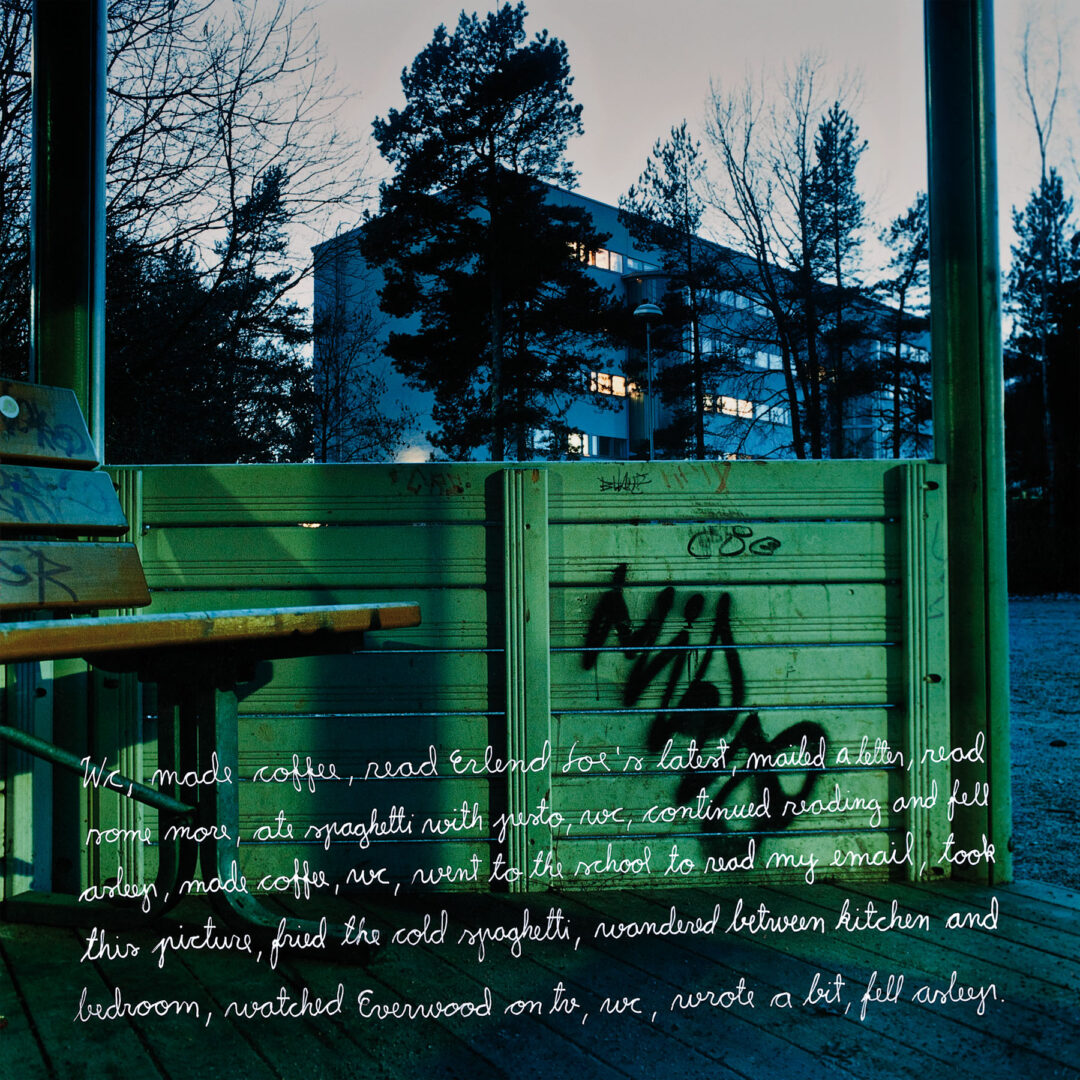

the pared- down dreams, longing, all the evenings

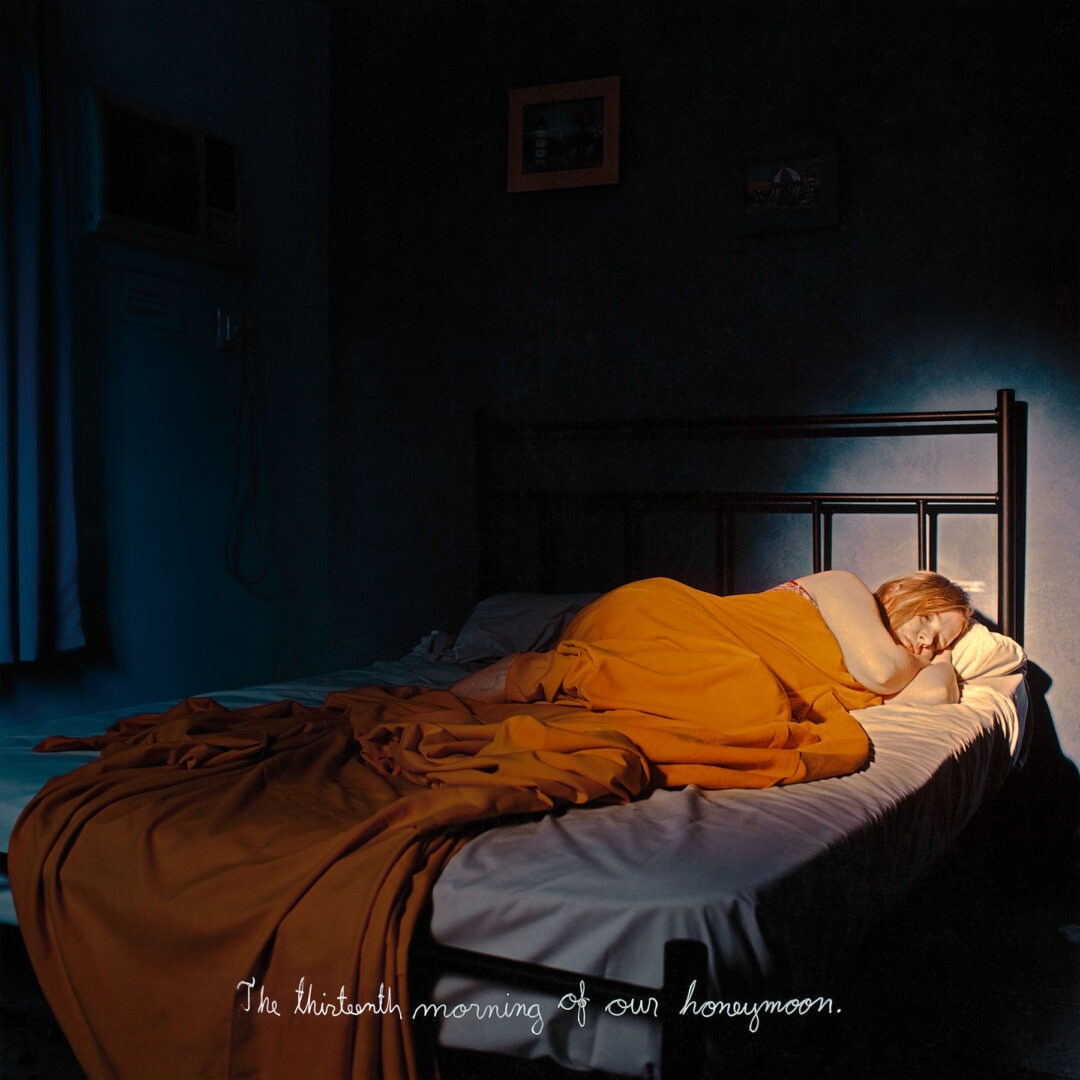

the touch of my coarse husband

lingering pleasure

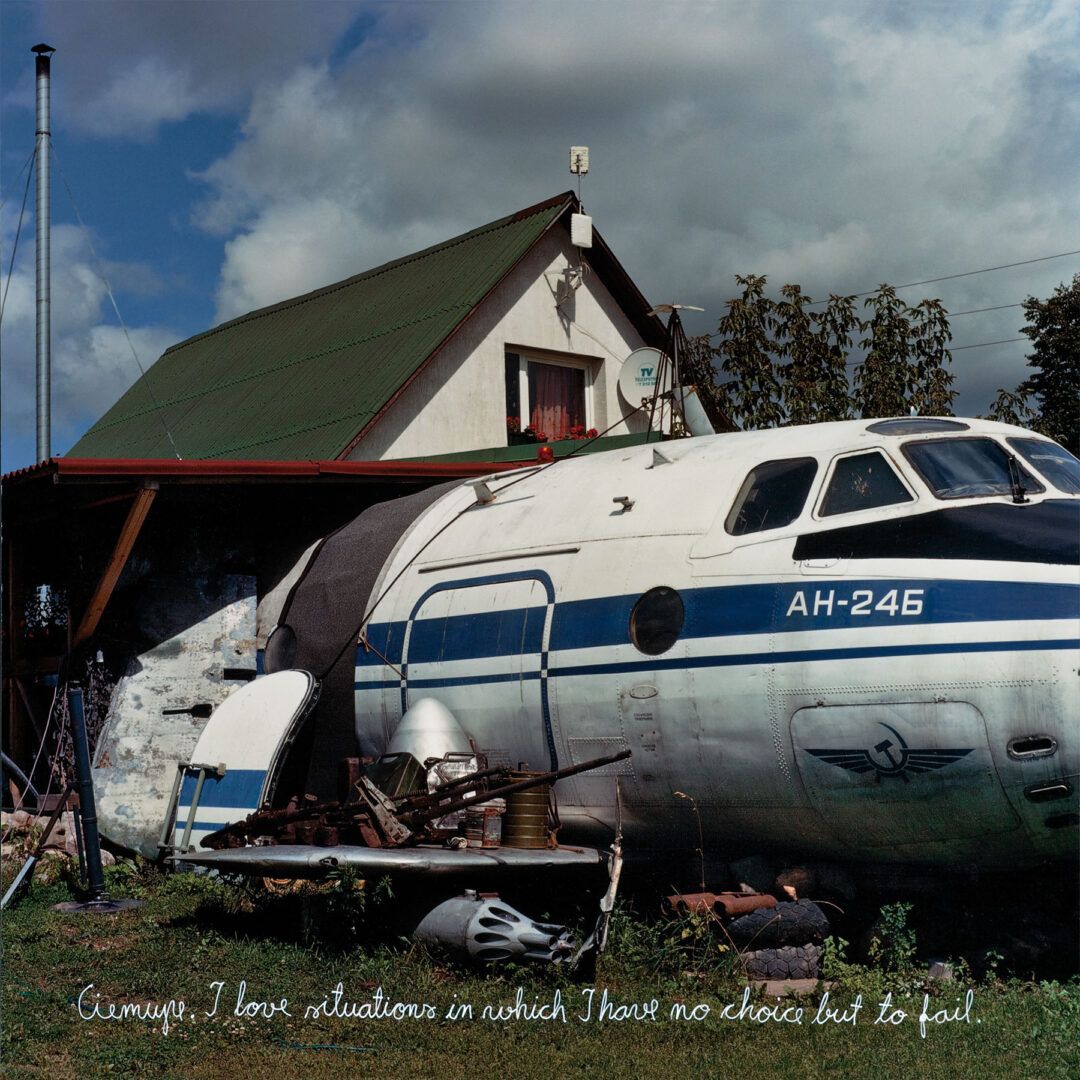

aircraft carriers,

the water which tastes of iron

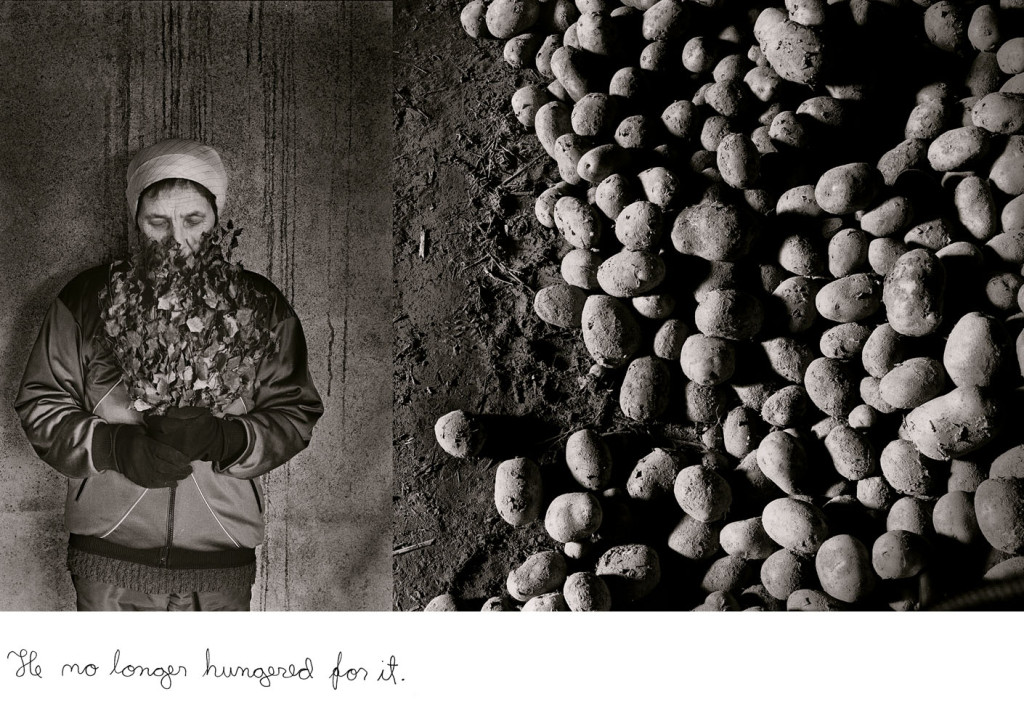

full stomachs,

empty stomachs,

the salty taste of many tongues

building the Wall

breaking of the Wall

liberation of Nelson Mandela

the broken dishes and the radio static

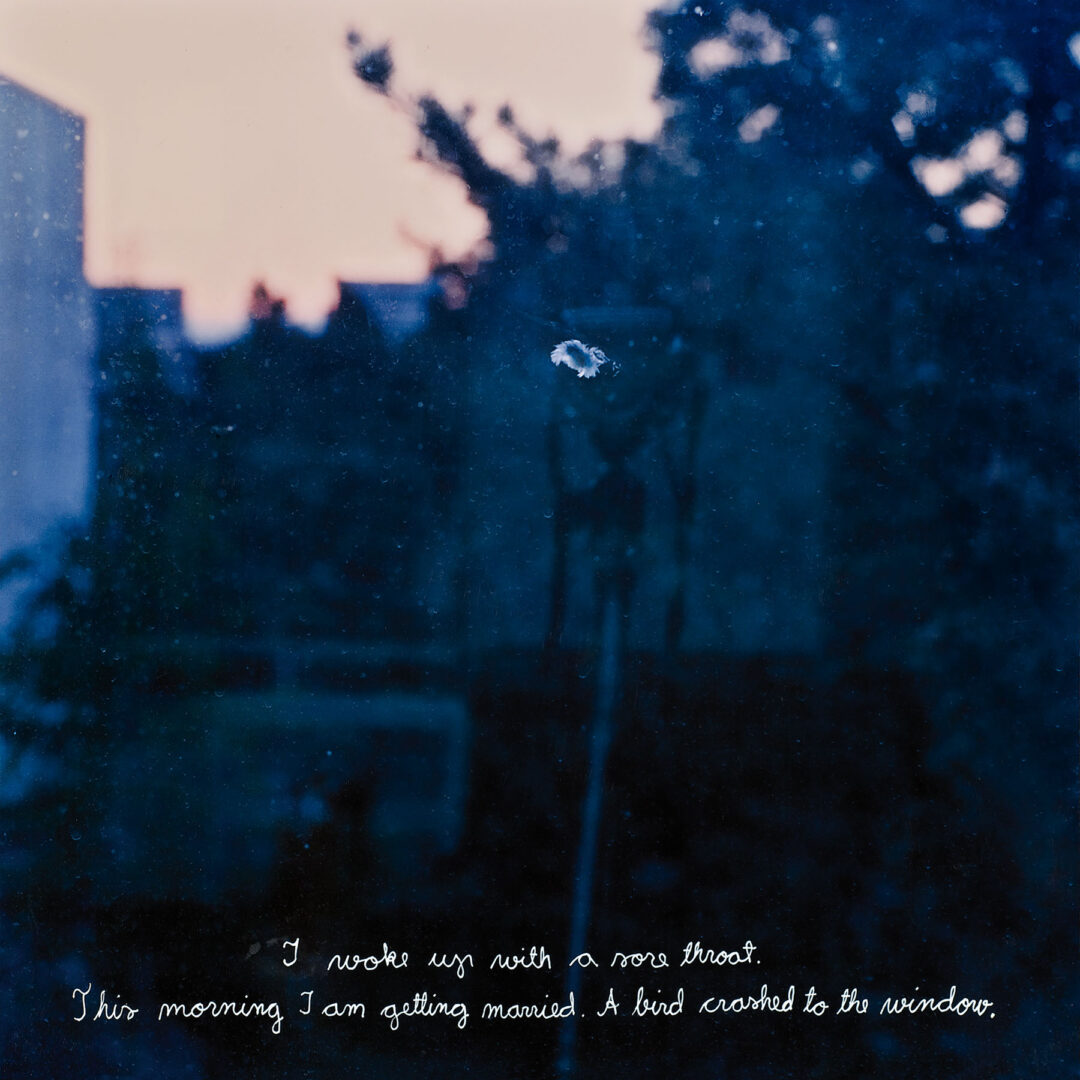

the Vietnam war, the thrown rice on Church steps,

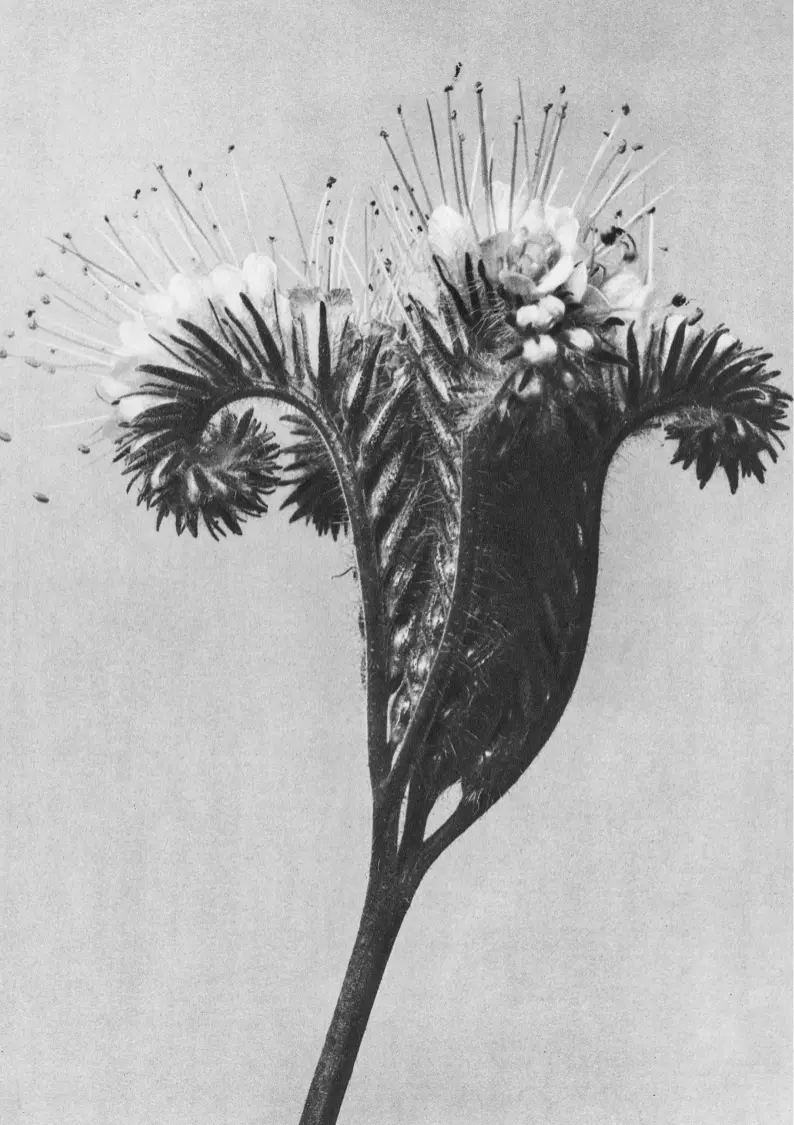

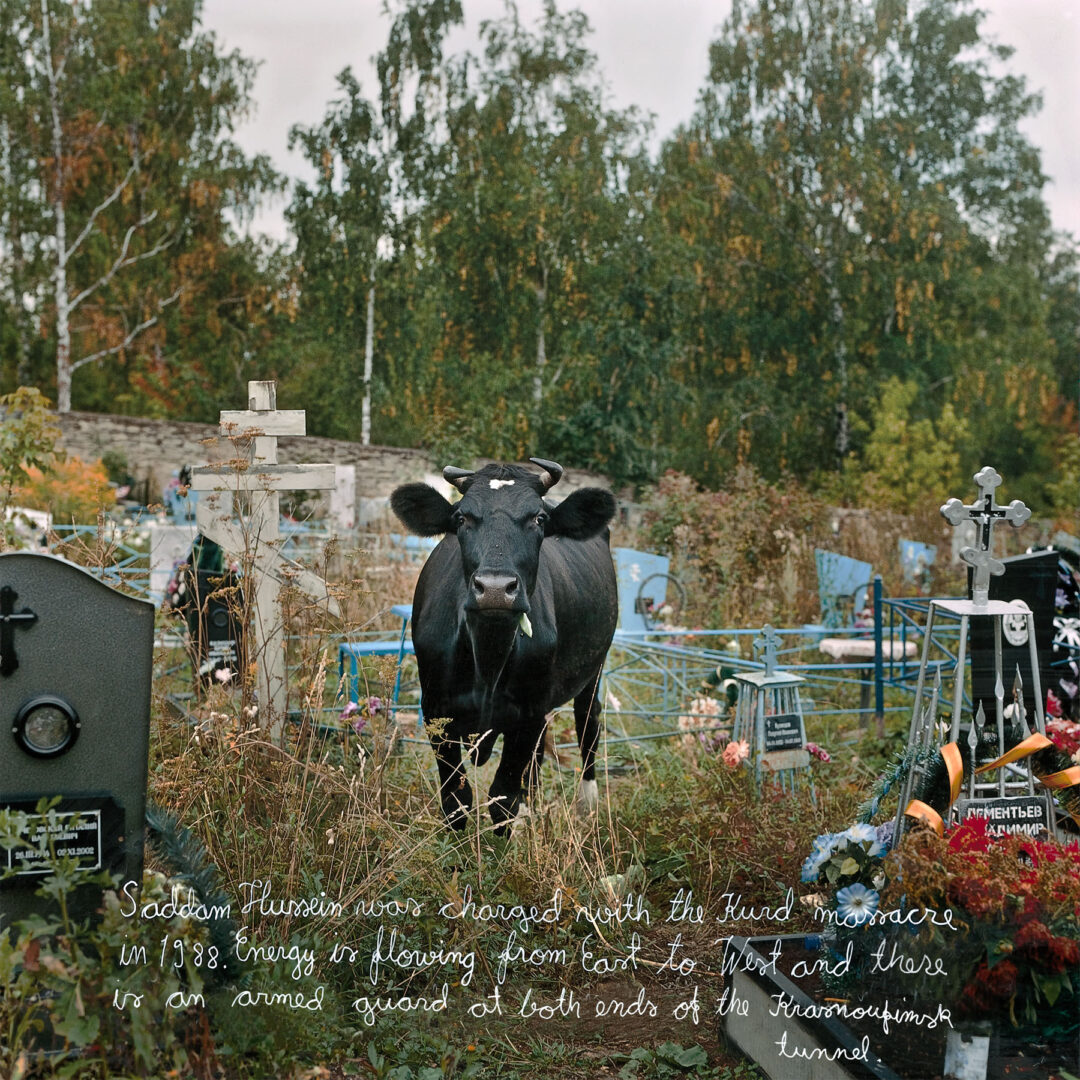

blossoms and withered flowers,

my grandmother’s bath robe,

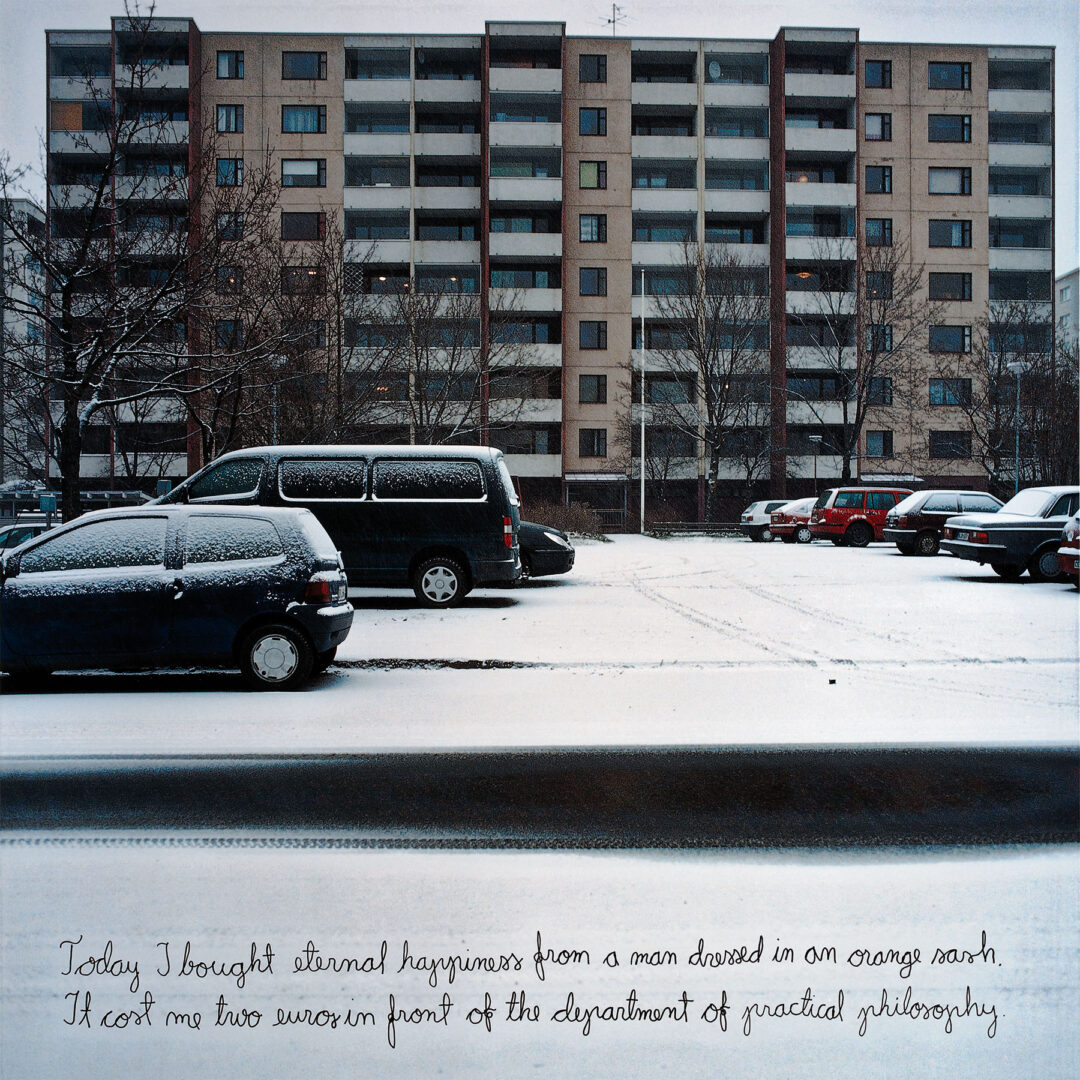

the long Sundays, the ersatz coffee

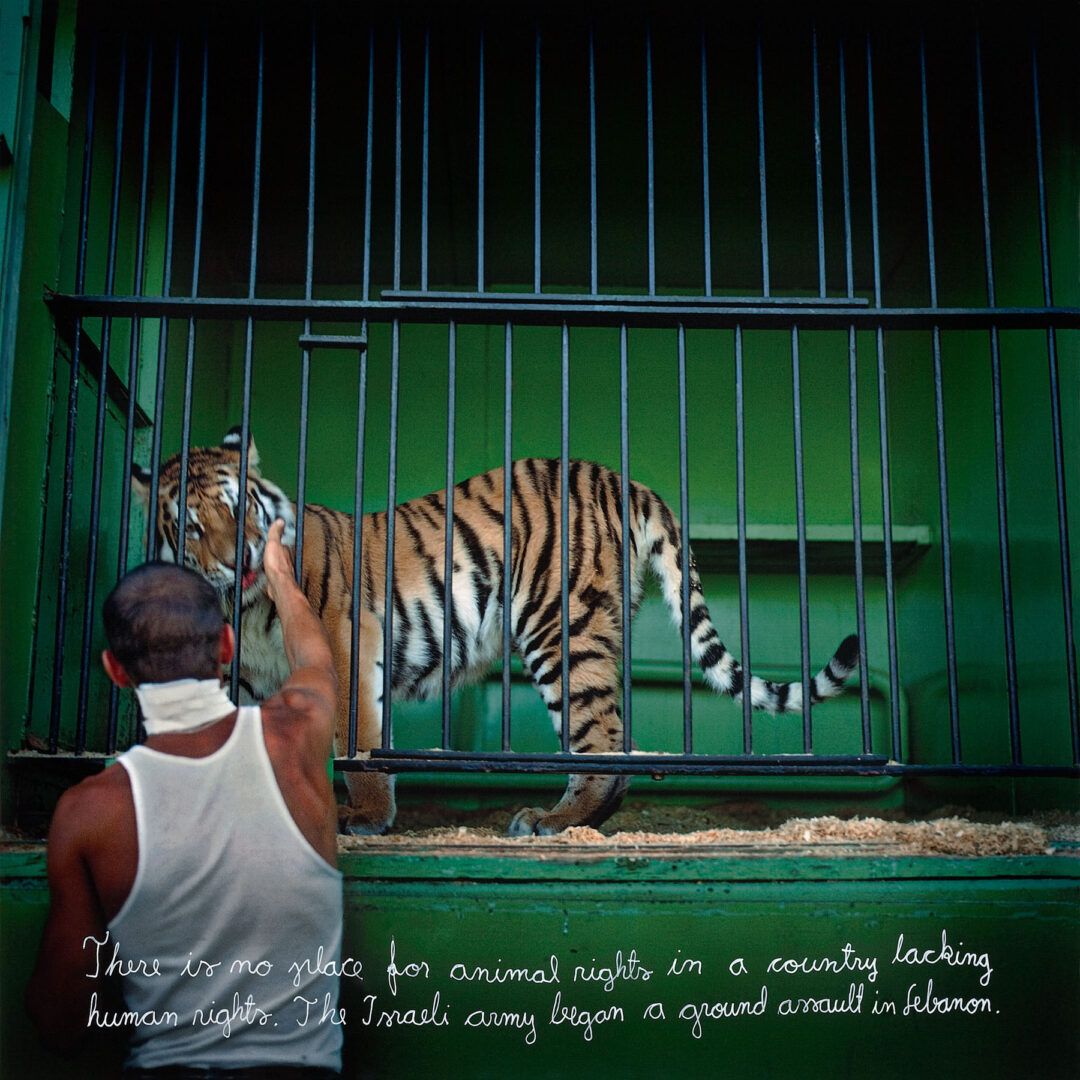

attractive bodies, suicide bombers,

the sunflower- patterned pants, four-o-clock rush hour

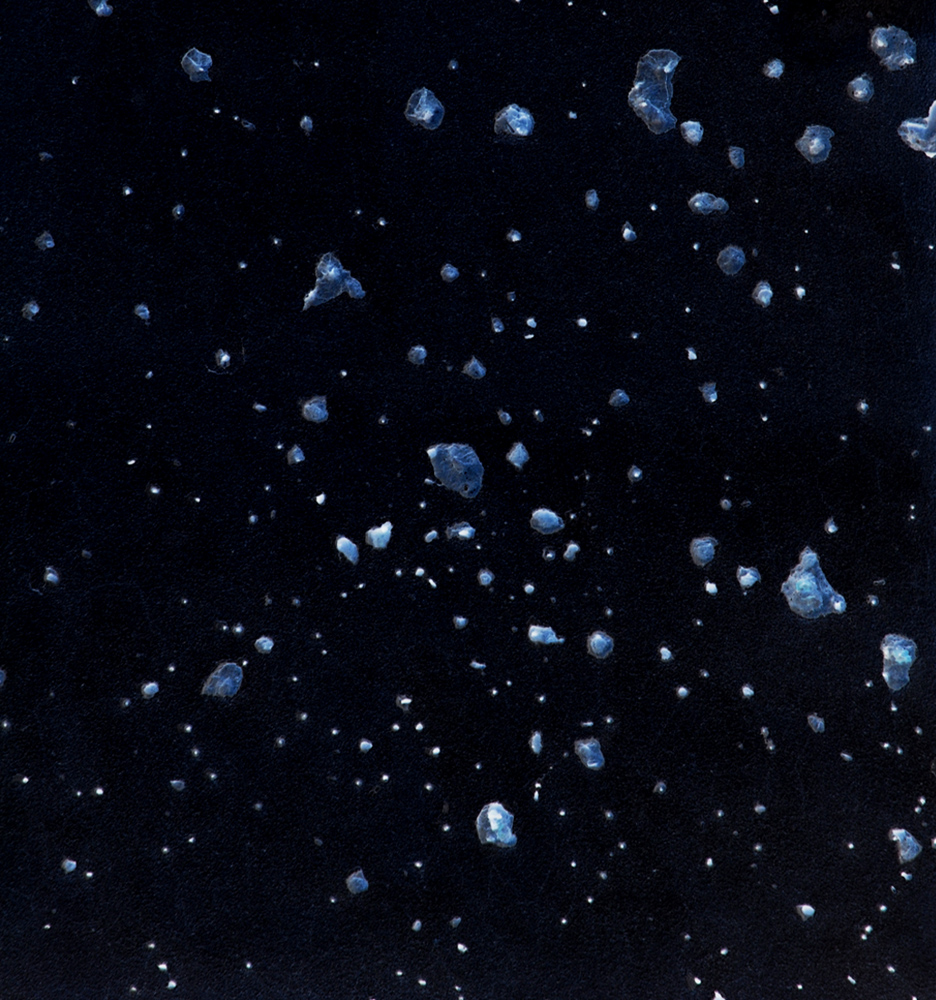

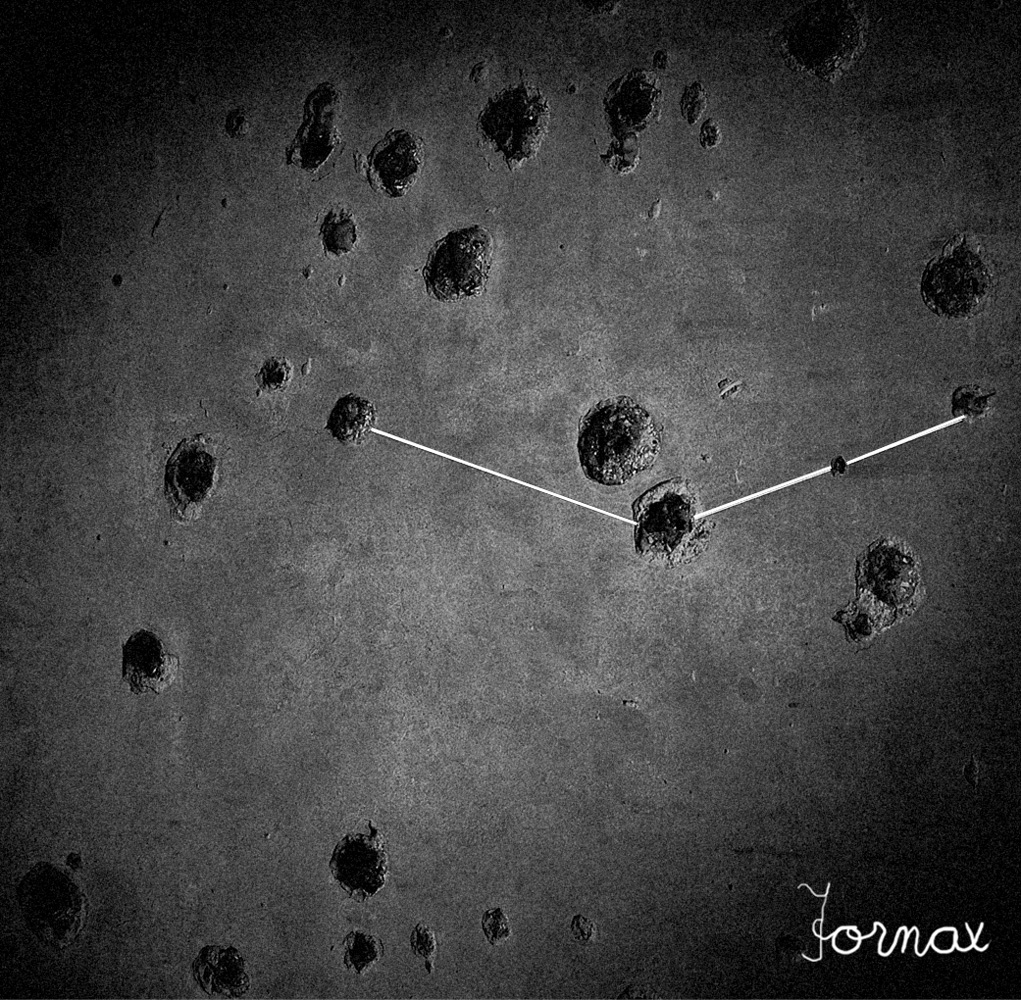

full moons

half moons

the unexpected homecomings

when Anna the neighbour’s cervix dilated giving birth

the insults, the proposals of marriage

the broken bridge of Haapamäki

the table settings

the smell of wet peat, the cry of my firstborn

questioning my faith

the sudden movements of my attention- seeking sister

the industrial development

the EEC, Laura’s worries about varicose veins,

money transactions

lakeside views on summer mornings

the roughness of touch

the changing shape of

love.

All this and still more.